The View from 1964

Corinna Kirsch seeks out artists, curators, critics, and art historians to respond to the Walker's exhibition "1964" for views on the mid-'60s scene, understanding art as a product of its time and the thorny issues raised by chronologically framed shows.

1964 IS AN EXHIBITION COMPOSED OF ARTWORKS from the Walker Art Center’s permanent collection that were — for the most part — created in the year 1964, and the show features many of the “big” names associated with art at the time, working in Fluxus, Minimalism, Pop, and Arte Povera. The specific chronological motif that unites these works, although easy for audiences to comprehend, makes for a complex curatorial model. When framing an exhibition of work around a specific time period, issues arise regarding the way in which museums and their curators to press into the history of art. How much does the fact of its creation in a single year or during the course of a single event actually tie an artwork to a specific historical moment? And how does one decide which of these historical moments are particularly definitive or significant — do you just consider the globally overarching political events, or is there room for the idiosyncratic, intimate details that affect individual lives? Looking ahead, how does such a curatorial model for exhibiting work affect recent art practice? That is, how will a given piece (inevitably) become relegated to history when it becomes a part of an institution’s collection? If we believe that it is these global events which unite art practice, we will surely have an Art after 9/11 exhibition during our lifetime, although I wonder how this type of curatorial framework could cohesively tie together artists as varied as Ryan McGinley, Mattias Faldbakken, and Katharina Fritsch.

Instead of writing a straightforward review of this exhibition, I wanted to continue a discussion of the many questions that emerge from a specific, chronological framing of art. I asked a variety — a goulash, really — of artists, curators, art historians, and writers to respond to issues raised by the Walker Art Center’s mode of presentation for the exhibition 1964. My aim isn’t to unearth from their opinions a unified picture of art-making during that time; if anything, I hope that the responses offered by the interviewees further complicate the notion of history as a set of multivalent narratives. Understood this way, history is active and mutable, like the waves of the ocean, continuously rising and crashing into each other at different times and locations, even if they’re all made of the selfsame water.

Respondents include: Tom Arndt, Hannah Higgins, David Little, Jessica Lott, Dianna Molzan, Sid Sachs, Roman Versotko, and Siri Engberg.

______________________________________________________

Dianna Molzan is a Los Angeles-based artist. She is represented by Overduin and Kite and received her MFA from the University of Southern California in 2009.

Q: What do you think an exhibition of work centered around the year 2001, or even 2010, might look like? How would your work fit into the fusion of variegated art practices that might be included in such a show, based on that temporal framework?

A: Just the other day, I was reading the intro to a book about design, from 1850 to the present (published in 1986), and it began: “As we move further and further into the 1980s, it seems less and less likely that we shall see the emergence of a ‘style for the ’80s’.” Thinking about that statement makes me hesitant to guess what an exhibition about the last decade might look like — anything I could come up with today would sound woefully naïve in the future.

Q: Is it important for an artist to think about their practice as part of a larger history? Or does this come after the fact?

A: That question reminds me of the expression “making history,” as if it is possible to know outcomes and cultural significance in advance. It seems that, regardless of whether an artist considers the larger historical context or not when they are making work, if the question is about timeliness, distinction, and longevity, it usually gets decided later, and by others.

Q: Are you haunted by any previous art movements?

A: Yes, by all of them!

______________________________________________________

Sid Sachs is the Director of the Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. Recently, he curated an exhibition on female Pop Artists, Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists 1958 – 1968.

Q: Why do you think there’s so much interest right now in art of the 1960s?

A: I think it is cyclical. Enough time has passed now that the artifacts [from that era] have been fully codified into a canon; now young researchers (and dealers) are looking for other avenues to approach the art of that period. As the artists pass away, foundations establish databases which allow for easier access to their bodies of work. Collections of previously marginalized works, such as the Silverman Fluxus collection, for example, can be purchased by or donated en masse to museums. The period can now be looked at, literally, from a historic distance.

Q: Much of the focus of the exhibition at the Walker, while staging a balance among the many separate and distinct modes of making that were apparent during the 1960s, is on a large number of works that were made by Andy Warhol. Can you discuss what sort of a presence Warhol had on Pop Art of the 1960s? I’m curious as to whether you think he, more than any of the other artists then in the New York scene, was even then a sort of an omnipresent, inescapable figure among his fellow artists — or if this is just an art historian’s retrospective designation of distinction about Warhol’s importance during the mid-1960s.

A: Warhol was obviously very important. However, he was not as well known as other Pop artists until about 1964. His method of working produced a huge body of work in painting, sculpture, printmaking, film, and entrepreneurship with publications, television, the Velvet Underground, etc. He was a master of promotion. Moreover, because he produced so much work of a relatively standard quality, and because he was handled by Ferus, Stable and Castelli galleries, he developed a large collector base. The market, the generosity of the foundation, and his museum also contribute to his importance. But it is perhaps mainly because of his diverse ideas and output, and that the work can be approached from many directions, which contributes to his lasting impact. Fifteen minutes is rarely that.

Q: With regard to your recent exhibition, Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists 1958 – 1968, what do you hope will be gained in terms of future presentations of work from the 1960s?

A: I hope it continues to be critically well received. I hope that, through seeing their work, many more women will be seen as important contributors to art in the 1960s. I also hope that someone has the good sense to make a Chryssa retrospective soon. Marina Pacini is working on a Marisol retrospective. I hope more of these artists get included in future exhibits. They have been ignored for a long time.

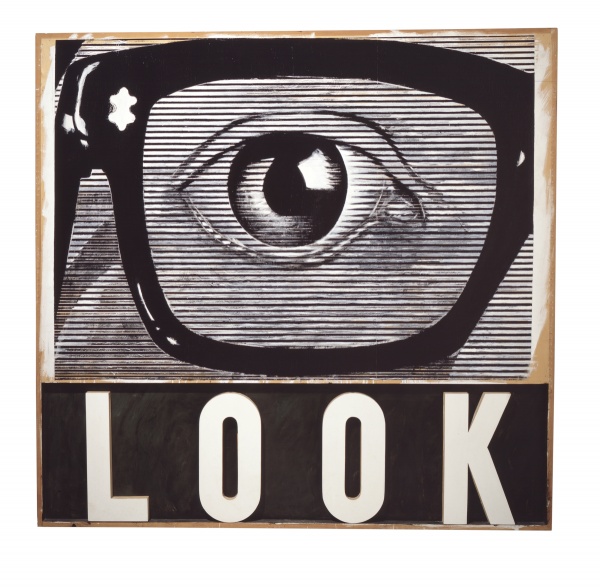

Q: Many of the works in the Walker’s exhibition invoke text, either through Fluxus’ dissemination of written materials, the screenprinted manifestations of commercial imagery in Pop Art, or through spoken performance. What have been the benefits of emphasizing text in (visual) art, both in the 1960s and now?

A: Legibility. And a wonderful, Zen inscrutability and openness, in the case of some Fluxus members.

______________________________________________________

Tom Arndt emerged as a photographer in the 1960s. In 2009, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts organized a retrospective exhibition of his work, Tom Arndt’s Minnesota.

Q: What were you doing in 1964?

A: 1964 was a little early for me — a year after Kennedy was assassinated. There was a cynicism about “Camelot,” but it was also a moment that started all kinds of revolution, particularly revolutions about identity. I was a freshman at MCAD at the time.

Q: What was MCAD like at the time?

A: It was a small little place — there were only about 300 students, so there was a lot of intimacy. Arnold Herstand [President of MCAD from 1964 through 1975] brought in famous visiting artists. I remember that it was a vibrant place.

Q: Was there a studio-based focus on photography at MCAD at the time? I’m curious as to whether the art schools acknowledged the non-commercial use of the medium then, or if the study of photography was relegated to, say, journalism departments?

A: There were no real photography classes [at MCAD] at that time; I studied Graphic Design for photography. But the University of Minnesota had an MFA program in photography, with people like Jerome Liebling and Elaine Mayes.

______________________________________________________

David Little is the Curator of Photographs and head of the Department of Photographs at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Q: 1964, although nominally focusing on “new intersections among visual art, performance, music, film, and graphic design,” centers on the moving image primarily as a document of performance (e.g. Carolee Schneemann and Yoko Ono). How were visual artists using photography in the 1960s (and in 1964, in particular) as a corollary to their art practice?

A: Artists have always used photography in a variety of ways, going back to Man Ray and Duchamp. Still, there was something of a divide between those who took photographs exclusively and those who “used” photography, as you suggest, as a “corollary.” In the early 1960s there was a divide between [those who use the camera exclusively in their work, and] photographers and artists who picked up the camera to take pictures of performances, or who did it on the side. Now, this sense of separation is subsiding, but still exists to some extent.

Q: How were artists associated with Pop Art using photography in the 1960s? (E.g. examples from Ed Ruscha and Andy Warhol are included in the Walker’s exhibition.)

A: They used photography in a variety of ways, but primarily as source material for their works in other media.

Q: What do you think were the most exciting ways photography was being used in the 1960s (or 1964)?

A: I don’t think there is one way that is more exciting than another; I would prefer to say that great photographs were taken in the so-called ‘straight tradition’ (Frank, Arbus, etc.), as well as in more experimental approaches (conceptual, performance, etc.). What is exciting is that they coexisted together.

______________________________________________________

Jessica Lott is a New York City-based writer and the winner of the 2009 Frieze Prize for Criticism.

Q: Even though organizing an exhibition around the year 1964 can appear to be a significant, even useful historical hook, a show themed around a moment in time also strikes me as somewhat arbitrary, as a conceptually untenable framing device — why not an exhibition around 1965, or April in the Bowery District, or Art Made After Work? What are other curatorial strategies that have tried, whether failing or succeeding, to use time as a framework?

A: With a thematic or conceptual exhibition, my guess is there is usually a lot of wrangling over a title that will have meaning, and will be comprehensive and yet not too restrictive, and which will entice the public. A tough business.

Q: Many of the works in this exhibition invoke text, either through Fluxus’ dissemination of written materials, the screenprinted manifestations of commercial imagery in Pop Art, or through spoken performance. What are the benefits of emphasizing text in (visual) art, both then and now?

A: As for text in art, it does often seem to be mentioned hand-in-hand with protest art, doesn’t it? Your question puts me in mind of a show I saw last fall at MACBA in Barcelona, called “On the Margins of Art: Creation and Political Engagement.” A very small show with a very big theme. This was sort of the inverse of what Walker’s doing — the time span was broad and the focus (also broad) was on politics and art, always strange bedfellows. But effective somehow, at least in the sociopolitical realm. Meaning becomes paramount here, the transmission of a concise idea, and the text/art combo delivers a punch. Or maybe it just directs the hit so it lands more accurately. I’m thinking of the Guerrilla Girls, and also of some Adrian Piper (a big favorite of mine), and the Barbara Kruger pieces I saw in that show, although when I think text/art, I think Jenny Holzer.

I’m getting a bit out of my depth…but when you remove the politics/protest component, the relationship between writing and art, as two art forms, still seems a bit uneasy, aesthetically. This is something I would like to look into deeper, as a creative writer, in my own prospective partnership with the installation artist Karrie Hovey. Can writing, as writing with its own particular aesthetic language, coexist with visual art, which tends to speak in a different tongue? Be interesting to find out.

______________________________________________________

Hannah Higgins is an associate professor in the Department of Art History at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her publications include Life of the Grid (2009) and Fluxus Experience (2002). She is part of the present day art history association of Fluxus.

Q: Was there ever a strong Midwestern component to Fluxus? If not, why is it that this practice focused on democratization and decentralization was located in urban areas?

A: People cluster in urban areas, so it is more likely for advanced thinking to originate there since there is a density of conversation in cities. That said, many Fluxus artists eventually migrated, and the conversations continued. Dick Higgins, of course, went to California in 1970, and then to Vermont in 1971-1975. He ended up in upstate New York until his death in 1999. Robert Filliou settled in Villefranche-sur-Mer in France. Takako Saito has lived in Dusseldorf since the late 1960s; it’s a city, but a small one.

There are many others, not to mention the travelling exhibition/participation FLUXshoe, which travelled all over England in the 1970s, under the auspices of Fillipe Ehrenberg and Takako Saito. Better than the urbanist model for understanding the Fluxus network is the mail art model, with many nodes in the network. Admittedly, cities played a role in the early moments, but this was not a merely urban phenomenon.

Q: The current exhibition at MoMA, Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present, restages Abramović’s previous performances while at the Walker Art Center; Fluxus’ actions are represented through newsletters and filmed performances. Which curatorial model — that of treating the works of the 1960s in an archival manner, or that which handles work as an active set of instructions which can be continuously re-performed — is more suitable for a historical treatment Fluxus?

A: This polarization reflects a common misperception about the nature of Fluxus. Fluxus artists have actively performed (not re-performed) their events since the late 1950s (before they called themselves Fluxus), with a steady stream of performances, through to the present. Art historians, on the other hand, like to isolate artists as belonging to this or that decade. This framing, while it lacks historical accuracy, makes for neater, teleogical history writing, and it is very well suited to artists who perform a work once, like Abramovic, and then re-perform it decades later. This is not an evaluation of Abramovic (she is sincere in the work), but it is an indictment of normative art history. The historic photographs you refer to reflect the powerful practice of a handful of photographers (Peter Moore, George Maciunas), whose work has been used by the dominant collection in the US to build the photographic record of Fluxus. It helps that both photographers are deceased, since this apparently closes the book on Fluxus performance practice. That said, there are photographs of recent Fluxus prformances that can be seen on most of the artists’ websites and in European museums that don’t subscribe to the American modeling of Fluxus. See, for example, the Roskilde Museum Fantastiks‘ archive and the photographic holdings at the Tate Modern.

______________________________________________________

Roman Versotko is a Minneapolis-based artist and Professor Emeritus at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD).

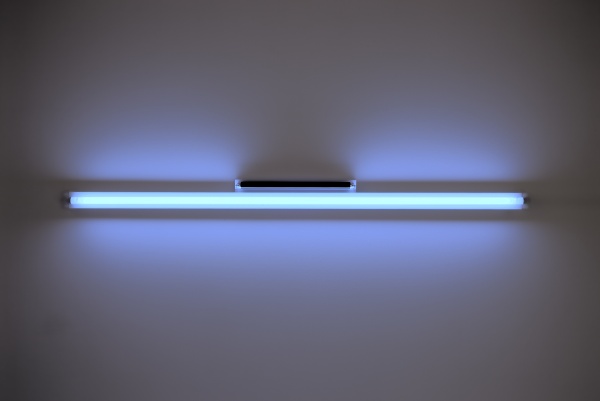

Q: In 1964, like many museum exhibitions about this time period, straight photography and “technology-based” art is relegated to a category of its own, as somehow separate from the rest of artistic discourse of the period. What was your experience like working with art and technology in Minneapolis and MCAD during the 1960s?

A: My contributions and work in the area of art and technology spans over 40 years, with my pre-algorist work dating back to the 1950s. My mature work with electronics and art came to be the algorist work that I continue to develop. When I came to MCAD in 1968, I brought my electronic synchronizers, camera, copy stand, projectors, and Wollensak Tape Deck with me (along with all my painting paraphernalia), as well as my slides and my reference library. My work has been immersed in art and technology since the 1960s, both as an educator and as an artist. I introduced a course on “Art & Technology” at MCAD shortly after I came here in 1968.

______________________________________________________

Siri Engberg is Curator of Visual Art at the Walker Art Center. She is curating From Here to There: Alec Soth’s America which will open at the Walker in September 2010. She has curated touring exhibitions for the Walker on artists including Kiki Smith and Chuck Close.

Q: In general, how did the idea, the impetus, for the exhibition come about?

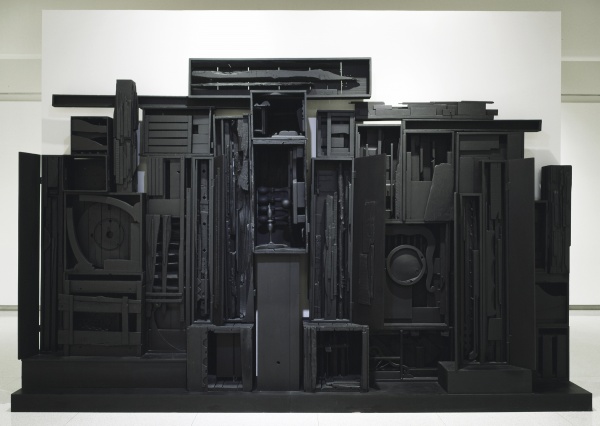

A: That’s actually the first question a lot of people have been asking; that and “why 1964?” The idea for the exhibition actually came about because of the way our collection has come together. I was thinking about doing a show about the mid-60s as a moment of high pop art; initially, I thought of it as just a straightforward pop show. After really combing through the Walker’s collection, I realized that 1964, in particular, was the year, not only that a lot of works in our collection were made, but when we acquired a lot of works at that particular moment. Then the exhibition started to become a story, specifically, about the development of the Walker’s collection. It could’ve been 1965! I do use “1964” a bit loosely, because the works in the show all come from that mid-’60s zone; but mostly that year, 1964, was the anchor for it.

There are three major George Segal sculptures in the collection; one is a recent acquisition that’s being shown for the first time in this exhibition, and they’re all from 1964, so that was another reason for how things had started to come together this way. What I also started to realize, after going through the collection, was that it wasn’t only an incredibly fertile moment in terms of the development of Pop, but that there were so many other movements which had also, by that moment, really started to take off. It seemed like focusing on one year would really give you a nice framework for looking at all those disciplines, movements, and impulses that were starting to percolate at that time.

Q: Based on what you’ve said here, while it seems like 1964 may have been a very “pregnant” moment in the United States — in terms of art, in terms of social reforms — it still wasn’t a moment with the sort of shifts and cultural eruptions occurring in, say, 1968. Not yet.

A: I think that 1968 was an incredibly different time from 1964. We talked about this a lot as the show was coming together. We would sometimes pull out a work, say from 1968, for consideration, but the impulse was too different. There is a real shift that happens from the mid- to late ’60s. I think that the 1964 show starts to demonstrate how much was going on in New York at the time; it’s an incredible reflection of not only how art was changing and breaking away from Abstract Expressionism, [but] of the idea that the found object was an absolutely legitimate form of artmaking, and the idea that the artist’s hand wasn’t necessarily important anymore. That was a huge change. By the late ’60s, certainly by ’68, both here and abroad, it was a very different climate, even socially. But starting in 1964, a year after Kennedy’s assassination, all of these things started to signal a coming shift, that we were living in a different time.

______________________________________________________

Related exhibition details:

The exhibition, 1964, will be on view in the Walker Art Center‘s Friedman Gallery through October 24.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Corinna Kirsch is a curator and writer currently living in Minneapolis. She received her MA in Modern Art History, Theory, and Criticism from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Motherwell Journal, …might be good, Proximity Magazine, and ART PAPERS.