The Rules of a Dance Exchange

Carl Atiya Swanson parses a recent, unusually participatory evening of dance at the Walker Art Center: David Zambrano and company's performance of the largely improvised series of solos against classic soul tunes, "Soul Project."

“IT IS GOOD THAT WE DO THIS IN A MUSEUM,” Venezuelan dancer and choreographer David Zambrano announced to the crowd at the Walker Art Center on Friday, May 11, “because we have made a little gallery.” Resplendent in a tailcoat and trousers cut from a Dutch waxprint cloth in blues, yellows and greens, patterned with microphones and tangled cords, like a circus ringmaster or a walking Yinka Shonibare sculpture, Zambrano made a brief appearance before the show to prepare the crowd for his Soul Project dances, a series of improvised solos set to classic soul songs. The evening was already unorthodox; as the ticket-holders entered the McGuire Theater, they found the heavy black curtain drawn across the stage, a bar set up in front and general milling, before a side door opened and everyone was ushered through backstage to the curtained-off stage area. With no set and no music playing, there were occasional nervous titters as people realized that they were in for something more participatory, and potentially more invasive, than a simple a dance presentation.

With his curled grey hair parted in the middle and squared goatee shooting off to opposite sides of his chin, Zambrano would not have looked out of place announcing for Barnum & Bailey; he genially made his way to the center of the gathering and welcomed the audience. Accompanying him was the Mozambican dancer Edivaldo Ernesto, who gave a brief, intimate display of what we could expect throughout the night. Hoarsely belting out a few lines from “Be Careful, It’s My Heart,” by Cuban songwriter Bola De Nieve, Ernesto jabbed at the air with tightly controlled lunges and an articulated tension that caused him to shake; with his movements, he carved out a space on the dance floor before finishing with a calm release.

After they ended their preliminary demonstration, Zambrano and Ernesto thanked the audience and disappeared. As they did so, the lights went down, several spotlights lit up the stage and Ike and Tina Turner’s take on the Otis Redding-written, Aretha Franklin-famous “Respect” filled the room. Zambrano was canny to use versions of familiar songs not performed by the artists most associated with them — it subtly underscored a notion of sharing and evolution in the work, both in terms of artistic practice and sharing with a wider audience; as with being asked to wander around on the “stage,” the unexpected musical choices also had a slightly disorienting effect. As we waited, some in the audience danced, but in that room full of members of the Twin Cities’ dance community, it was mostly the animated amateurs who took an occasional, laughing step into the light.

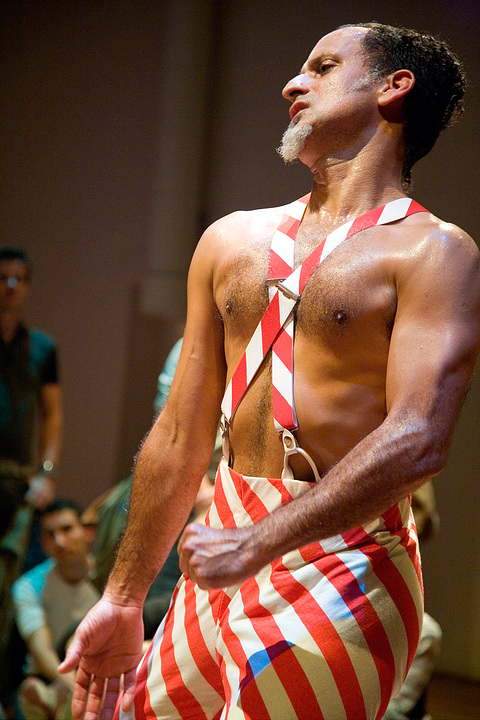

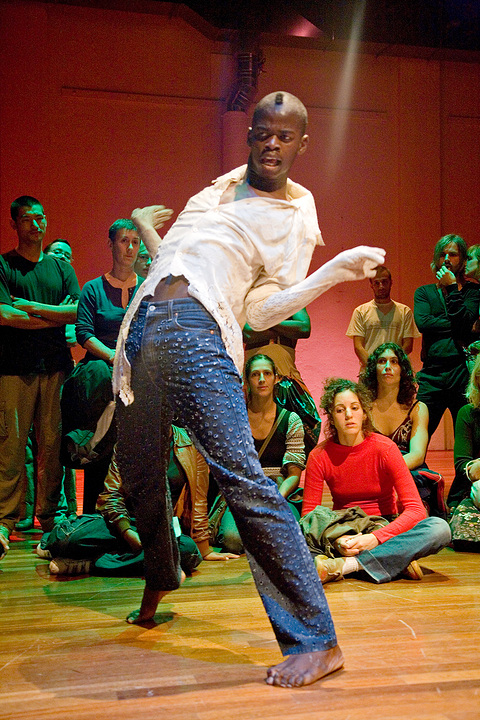

After a brief wait, the company of professional dancers made their way in, costumed along a circus theme. Slovakian-born Milan Herich — broad-chested and shirtless, with a dapper Continental part in his hair and neatly trimmed moustache — strode out in a pair of red-checked pantaloons, an apt strongman. Fellow Slovak Peter Jasko emerged wearing an ultramarine blue unitard, gold sequined diamonds running up the sides, recalling a harlequin; Slovenian Nina Fajdiga followed just after, and outfitted in a black unitard with neon polka dots, a grass skirt, and chest-piece of fuzzy neon balls, she seemed ready to serve as the evening’s all-purpose clown. Ernesto — decked out in distressed denim and a white shirt, with lace gloves that climbed all the way up his arms — was vaguely leonine in the enormous, shaggy strawberry blond fright wig he wore through most of the show. South Korean dancer Young Cool Park, with his asymmetric long hair and leather bolero jacket looked every inch a K-pop star. Another performer from Mozambique, Horacio Macuacua, wore a tan jacket and skirt combo, printed with architectural paisley detailing along the hems and seams; an array of medals and bottle caps was pinned to the front of the outfit, which he used to mesmerizing, rhythmic effect during his first solo.

Even with the show’s unusual staging and as intermingled as the audience was with the action on stage, the carnival of costumes left no confusion about where our attention should be, making it instantly plain that Zambrano’s dancers were there to perform.

In conversation after the performance, Zambrano noted that the mechanism for Soul Project is one of chance — the company has worked together to develop a vocabulary, and they know which are their solo songs, but once everyone is in the room, the iPod is put on shuffle – all the dancer knows for sure ahead of time is that when their song comes up, it is their turn to dance.

The night I saw the performance, Fajdiga did the honors to open the show with a solo for James Brown’s “Your Cheatin’ Heart;” she blended elements of the Charleston and ballet with low, scuttling floor work, and made piercing eye contact with audience members, her face mostly set but for an occasional, teeth-baring show smile and laugh. Zambrano carried on with that eye contact and impassioned facial expression through his dances as well, the torch songs “And I’m Telling You” by Jennifer Holliday and “Let Me Down Easy” by Bettye Lavette.

______________________________________________________

With the shakes of a person possessed, Macuacua shuddered across the room and forced two women off their seats against the wall, finishing his dance by rolling his body off the commandeered platform, over a well-appointed purse, knocking a stylish coat off the block seat in the process.

______________________________________________________

In an interview printed in the program notes, Zambrano is asked if he considers the dance world to be without borders; he replies, “I would say not yet. The dance world you are talking about is the Western dance world. We have been influenced by only one side of the world so still I think we can have more exchange.” That exchange was manifest in the dancing itself, but became more problematic when not initiated by the performers. For example, in his second solo, one audience member took Zambrano’s direct gaze and thrusting arms as invitation to push for more interaction, which the dancer gamed, teasing, pulling his hand back, eventually using left foot to poke that audience member under the right armpit. That contact, under the control of the dancer was funny and playful, but when the audience member grabbed the foot and held on, it seemed like a violation. Even though the setup of the performance broke down the usual divisions of proscenium and stage, Zambrano still maintained the notion of the gallery as an inviolate space; touching the kinetic “sculptures” therein felt like a breach of etiquette.

Zambrano created mini-narratives of heartbreak in his solos — seeming to cut his own strings as he plunged to the ground, tearing out his insides — but sorrow was not the driving motivation for these dances, nor for the chosen music. After all, songs about heartbreak are rarely about the despair itself, but about the defiance that follows, the act of throwing out the pain to keep on going. Even the more fluid dances, like Peter Jasko’s lilting, folded take on Aretha Franklin’s “Night Life” emphasized that resilience — Jasko bouncing down to the sides of his feet and then back up, a blend of b-boy and ballet.

These were no silly little love songs, and the dances were not a lighthearted exercise in technical prowess. That was especially obvious in Horacio Macuacua’s incendiary dance to the Baby Huey rendition of “A Change Is Gonna Come.” Using the same tense, stuttering physical vocabulary, punctuated with bursts of enormous movement, established throughout the evening, Macucua’s solo for “A Change Is Gonna Come” was the highlight of the night. He steadily built the dynamic of his footwork, from tapping low on the ground to a stomping thunder, paired with a face-warping howl, all as the Civil Rights anthem rose to meet him, until Baby Huey set forth the quasi-stoned revelation that, “there’s three kind of people in this world, that’s why I know a change has gotta come. I said there’s white people, there’s black people, and then there’s my people.” With the shakes of a person possessed, Macuacua shuddered across the room and forced two women off one of the blocks set against the wall for seating, finishing his dance by rolling his body off the commandeered platform, over a well-appointed purse, knocking a stylish coat off the block in the process. As a black, African dancer stating his presence and power to a mostly white, Western audience, Macuacua took the “can have more exchange” of Zambrano’s interview and, like the song, made it an imperative: “gonna have more exchange”.

After the solos finished, the final act was an invitation from Zambrano and the company to dance as a group to Aretha Franklin’s “Spirit in the Dark,” a tune which would have been last heard on that stage during the November Choreographer’s Evening as a sample in Kanye West’s “School Spirit,” to which Kenna Cottman (who offered up her own thoughts on Soul Project on the Walker’s blog) performed and choreographed a dance. In ending as a group that mixed the audience and performer, Zambrano managed at once to repair the earlier breach and allow for the participatory release that many in the audience had been seeking. And those were the terms of this dance exchange he structured through the evening: Amidst apparent chaos and random chance, there are still rules around the power of artists over audiences, questions of the flattening nature of the world outside the performance. “Soul Project” is an attempt to puncture those invisible borders with present bodies, dancing defiantly.

______________________________________________________

Related links and information:

David Zambrano and company performed Soul Project at the Walker Art Center on May 11 and 12.

Listen to Zambrano discuss the show on a recent episode of TALK DANCE, hosted by Justin Jones. Read dancer/choreographer Kenna Cottman’s response to Soul Project on the Walker blogs.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Carl Atiya Swanson is a multi-disciplinary artist living in Minneapolis. He is a graduate of the University of Southern California School of Fine Art and is currently pursuing an MBA in Nonprofit Administration and Entrepreneurship at the University of St. Thomas. He blogs on arts & culture at CakeIn15 and is a member of the theater company Savage Umbrella. His first full-length script, Care Enough, is being produced by Savage Umbrella and will run at the nimbus theater June 1-16.