The Pressure of Beauty, the Beauty of Pressure: Fashion Here and Now

Lightsey Darst covers what is a perennial spring subject--fashion--but this is fashion with a difference. She visited four local fashion designers who produce their own lines.

Rising Tide?

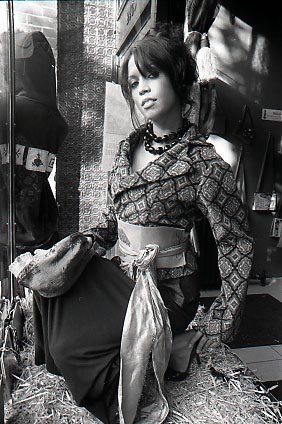

Four mannequins, some hanging from chains, some on stands, lean into the attic space of Saira Huff’s studio. Bright fabric—magenta gauze, blue satin—overflows from one rack, while another is crowded with clothes, some finished, some in the making, some half-demolished. At the far end of the room is a small window, the walls around it draped in furry green fabric, making a cozy yet somehow suggestive nook.

Huff’s sewing machines are pushed back into one side; a flat board ready for pattern-making occupies the side opposite the window. Two pairs of high-heeled platforms, one rain-slicker yellow, the other clear-strapped and glittery, sit on the board. On the mannequins are Huff’s artworks: a jacket in a lizard pattern with a high collar, no sleeves, and a diagonal zipper. A bikini and mini-skirt in stretchy black glitter, with another high, sharp-pointed collar. A purple stretch-velvet dress, unabashedly sexy. Two swathes of fabric on their way to being a dress, one narrowly pleated on top of the other, both brilliant mermaid colors, the bottom edges unfinished and jagged like fins.

I went out to investigate independent fashion design in the Twin Cities and got soaked. There are not a few designers out there carefully hand-sewing their strange new wearables; there are more like a hundred. I was originally inspired to write this article by the poster for the Retroflexion fashion show, but it turns out that fashion shows are popping up like CD release parties, in bars and shops and galleries all over the Cities.

Several stores—Cliché on Lyndale in Minneapolis, Wear It on Grand in St Paul—feature local designers. A local fashion magazine may even be coming out. I say may because the fashion magazine, like nearly everything else in Twin Cities fashion, is in its early stages. Searching for designers, I found half-finished webpages, tantalizing glimpses of couture dresses without contact information, and “coming soon” everywhere. I couldn’t tell whether the scene was coming or going or just slowly percolating, but several designers told me that it’s coming; independent fashion is on the rise. What follows is a sampling, not an exhaustive survey, of this art.

But first, is fashion design an art? Look at the clothes these four women make and you’ll see craft and design: they’re not just stitching up McCall’s patterns. Talk to them and they’ll tell you about their inspirations, like any other artist. Fashion isn’t abstract, it’s true, but the limits of clothing function and the human form actually feed creativity, just as the limits of the sonnet can. Fashion may have a purpose, but it’s no more narrow than the purpose of architecture: garments keep us warm or cool, but they also flatter us, make us feel good, and manifest our ideas. The four designers I talked to all had their own opinions about the art of fashion—as would be the case in any other art form.

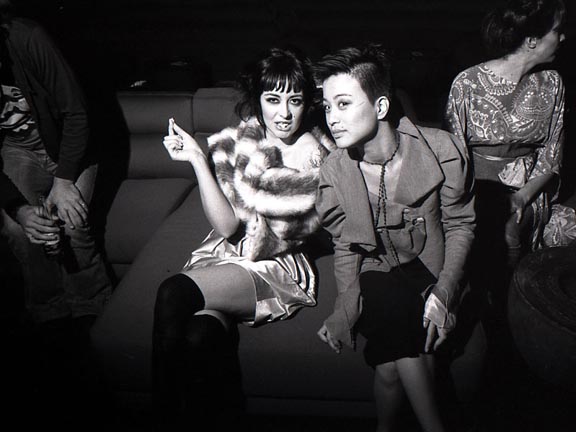

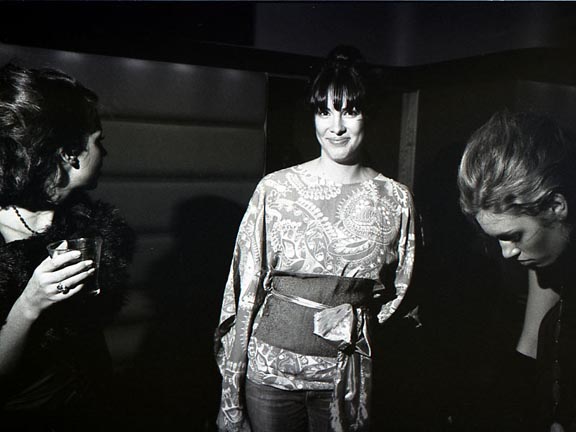

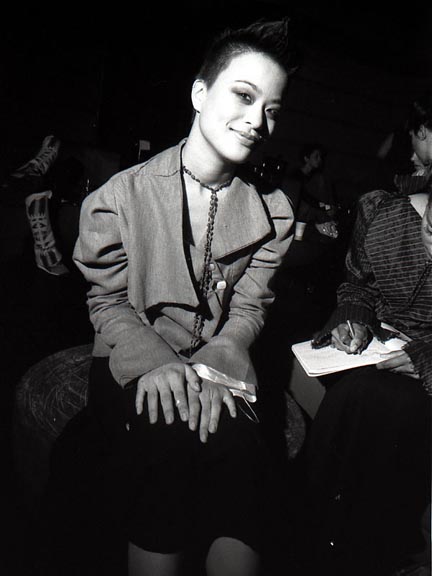

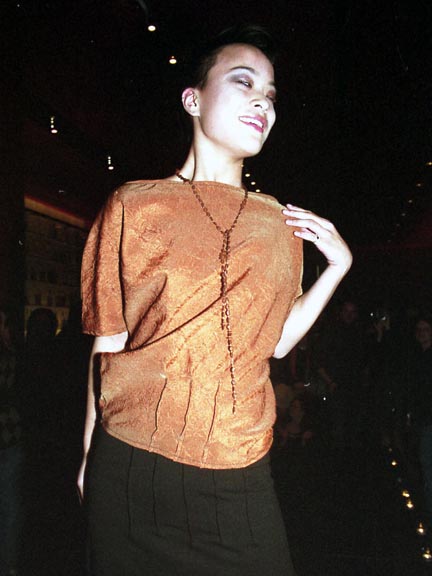

Kimberly Jurik: Less Than Perfect

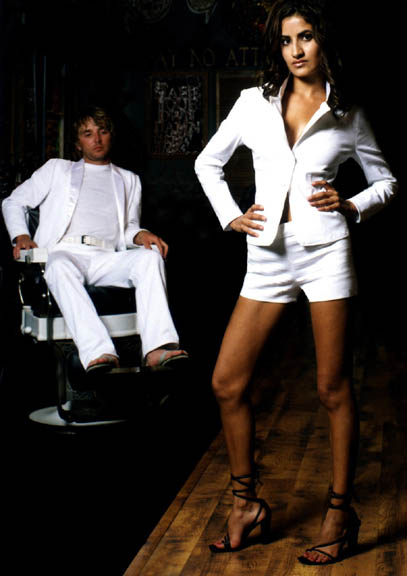

Kimberly Jurik, whose emerging label is called Less Than Perfect, is unusual among these designers in that she’s talking to manufacturers and planning to expand her business. She’s ambitious, in other words, while many designers are either content with their cottage industry or don’t think they could make a full-scale business out of fashion. But Jurik, who just graduated from an Italian design academy, sees herself as connected to a global fashion scene, even though she plans to remain in Minneapolis.

When I ask her why fashions change, and what trends mean, Jurik gives me a glimpse into the center of her art. Fashions change because inspirations change: Frida Kahlo, for example, is a current inspiration, along with soccer, the 1970s, Japanese kimonos, drapery, Victorian puffs and pleats, and couture (the idea of clothing made for a particular body). The art, then, is figuring out how Frida Kahlo and the international soccer scene can combine in a dress, a skirt, a shirt, that will be what we want to wear now. It’s an art of riding waves, of selecting and combining, of catching and heightening the current feeling.

For Jurik, creating garments against the stream of fashion wouldn’t make sense, because she’s making the clothes for other people, and, as she puts it, “we want to belong.” She’s interested, though, in clothes that fit different bodies in different ways, and she hopes to see more individual approaches to the fashion of the moment. If Jurik has a mission, it’s to challenge the dominance of one outfit or trend at a time; she calls the sight of girls in malls wearing identical pairs of low-slung, stone-washed jeans, crinkly silk camisoles, and bolero sweaters “excruciating”. “Some people’s only creativity is their fashion,” Jurik says. She wants to aid that budding creativity with her flexible, innovative clothes: “I can make a difference.”

What does the current feeling look like, as Jurik renders it? For fall, Jurik put out a line of clothing in mixed colors and fabrics—a heavy, loose-woven brown, a silky sky blue—alternately tight and tailored and loose and flowing. A brown skirt with neat pleats across the front terminates in two leg openings; a white, slightly jagged-edged tank carries ladylike double darts through the bodice. In Jurik’s clothes, a woman is smart, sexy in a less-obvious way (even the lower arm, revealed in drapery, can be sexual), and slightly elusive.

Jurik herself is enthusiastic, full of ideas, encouragement, and predictions. She promises that we’ll all be wearing obis around our waists and skirts with legholes in the near future. She’s not an elitist, either; when I tell her I’ve been out of fashion for a while, she says, “The great thing about fashion is that it will always be there for you when you want it.”

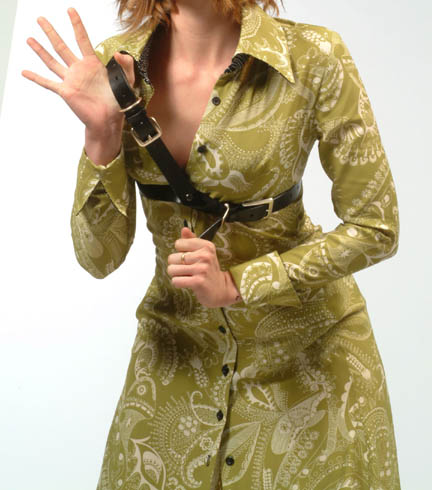

Kerry Riley: Red Shoe

When I first call Kerry Rileyof Red Shoe Clothing, she’s out of state photographing a horse competition. I wonder whether I’ve got the right person. But Riley, like most independent designers (and most artists), has two jobs. Later she shows me some of her horse photographs and explains what she’s trying to capture: the horse in action, changing gait, plowing through sand, taking a corner. What does this have to do with clothes? Riley’s not quite certain, but the more we talk, the more it becomes evident that she’s inspired by movement, “how the clothes will feel” and look in action. Her first fashion job was at a dancewear company where she learned about dance fabrics, different bodies, and how clothes move, and this influence comes through in the clothing she makes for her own line.

She shows me a red dress, tight in the bodice with a loose, flowing skirt—a classic, almost 1950’s dancing dress. She’s interested in the combination of comfort and restriction, which can, strangely, feel more comfortable than pure ease. A pair of pants with a boned, high waist reminds me of the strange security the boning in a tutu provides. Riley’s also been making one-shouldered harnesses out of old belts, which she shows over retro shirtdresses; the resulting outfit is all-purpose, ready for a party or a rock-climbing escape.

Riley wants to keep her clothing business close to home. She enjoys individual commissions, feeling that a one-of-a-kind flamenco dress has more of a future than mass-produced, fad-driven items. Her words for what she does—“the work we do [as designers] is so personal”; clothing design is “like sculpture around a body”; tailoring makes her “feel like a surgeon”—show that Riley’s paradigm is one garment, one body. She likes fashion’s ability to make people think, but she’d rather make your favorite Saturday night dress than an unwearable showpiece. The body of the intended wearer becomes a part of the creation.

Riley’s also inspired by fabric, particularly prints. She spots a white-on-red Eiffel Tower pattern in a calendar on the coffee shop wall and wishes she could get it as a fabric. What would it make? A wrap dress—a coat. . . “I can see what to make out of the fabric,” she says.

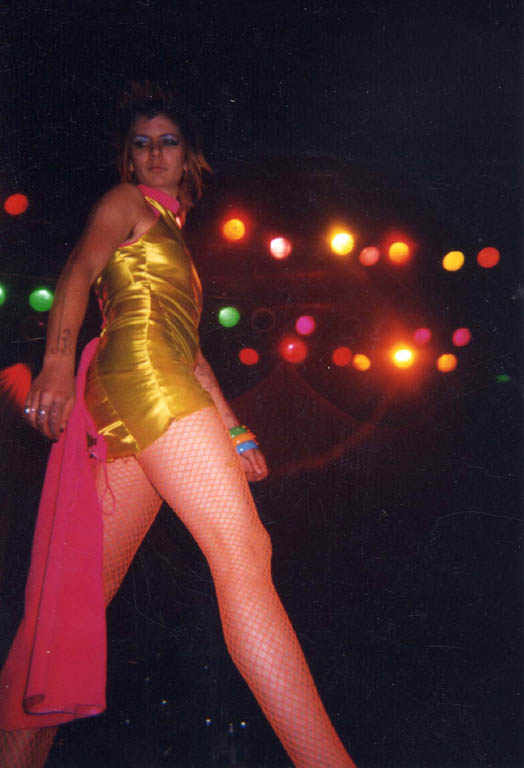

Laura Fulk

Laura Fulk fits more in the “wearable art” end of the fashion spectrum. Her latest line of clothes, which she’s preparing for an upcoming show, is based on the Great Depression. She has some old flour sacks her father found and she’s planning to turn them into dresses and skirts—not in 1930s styles, but in her own angular, asymmetrical style, marred by the multiple patches and repairs a Depression-era woman might have sewn to make her dress last. Fulk is “wary of trends”; instead, she creates her lines from different characters she’s interested in. Her most recent line featured post-WWII styles on the outside which open (with the ripping sound of Velcro) to reveal crazed, wildly embellished insides. With these dresses, Fulk wanted to invoke the situation of 1940s housewives with mental disorder—the ordinary exterior, the strain of keeping in the disease, the inner chaos.

Fulk is a busy woman. A bundle of iridescent black feathers is going to become a dress; she points to a professionally fluent, stylized sketch taped to the wall. She has four or five events to make clothes for already, and future projects stashed in bags around her room. Her photographs (one of a young woman holding a zipper in her mouth as if place of teeth) fill in the gaps where her walls aren’t hung with mannequins, designs, and materials. She works (sewing for a men’s custom big and tall, a job which has taught her a lot) and she’s also a student; she’s getting her BFA at MCAD in printmaking, photography, and sculpture (she already has an associate’s degree from MCTC). At school, she’s challenging herself to be more experimental with her materials and more conscious in her approach to art-making. Despite her success (Fulk has won awards for her designs), she seems to see herself in the early stage of her career.

Like some other designers, Fulk feels anxious about the industry she finds herself in, with its emphasis on beauty and consumerism. Her clothes often comment on the pressure of beauty and show the possibility of other, more ragged, types of beauty—rough edges, bright lines of unconnected stitches, fringe, asymmetry. So far her work has been more of a critical than a commercial success, although she has tried making some t-shirts as a less time-consuming effort. Still, she’s not sure how to put a price on her creations, or whether her future work will be more wearable and marketable.

In the meantime, Fulk is enjoying the creative chaos.

Saira Huff: Total Crap, UnInc

Saira Huff, like Riley and Fulk, has an interesting day job: she works at Venus, a clothing store mostly dedicated to strippers. Venus operates a booth inside Déjà Vu, and Huff also works there. The strippers come in in their thongs and heels and search for the sexiest outfits possible for them, given their individual body shape; from this Huff has learned a lot about what looks good on different types of bodies.

Huff’s clothes are overtly sexual—tight, short, low-cut—but it’s a comfortable, individual sexiness that Huff aims for. Like Riley, Huff likes to clothe “a really womanly body,” but she likes to challenge herself by choosing other body types for her models as well. “I think everyone’s attractive somehow,” she says.

Angular, bright, fastened with thin cord or savagely toothy zippers, Huff’s clothes manifest a punk lifestyle (one jacket reads “Insane Society” in embroidery; Huff calls her company Total Crap, UnInc), but spiked with a winsome and feminine sensibility. Sometimes her clothes exhibit the power of the female body—a skirt cut to reveal the bottom of the rear end, worn with tights, is flattering and hardass, not exploitative—and sometimes her clothes play with fairytale motifs—princess, mermaid, and ballerina evoked in her complex dresses.

I ask Huff about the art of fashion. “I tell people I make sculptures out of fabric,” she says. To some, worrying about clothes will always seem shallow: “I can’t expect everybody to care.” But Huff likes the utility of her art, its physical function and its ability to go with her everywhere.