The Memory Palace

Duluth artist and historian Matt Oman lives in his head, literally. He's spent years transforming his otherwise ordinary house into a "machine for mindfulness," a 3-D "materialization of a mind." And Ann Klefstad takes us on a guided tour.

MATT OMAN RECENTLY GRADUATED FROM UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA-DULUTH with a history degree, but his house is a work of art. His very ordinary home has become, through his sowing of books, images, arrangements of objects, and more, a kind of machine for mindfulness, a way of externalizing and developing ideas. It’s a three-dimensional materialization of a mind.

He’s compiled his interests in physical form and arrayed them inside his living space in a most curious way. Some of the thematics are: books, Zebulon Pike, mountains, skiing, snow, Pawnee cosmology, baseball, blue jays, dogs, the signs given out by the forms of living beings (say, the forms trees take when they grow, and how those forms are retained in driftwood). The flows that shape the dead are also important: how does water form wood and rocks? Art, personal history, the nature of persons, the workings of color and form — all are part of Oman’s concrete imaginary.

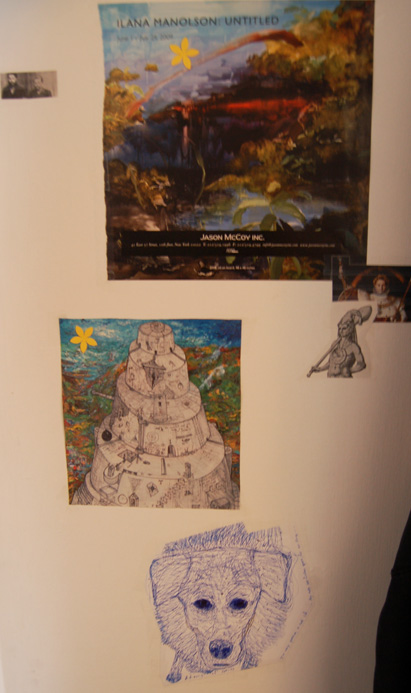

Only recently has he thought of all this as art, and only recently has he begun looking at other artworks, “but now I love it,” he says. “Looking through art magazines is one of my favorite things.” And Rembrandt self-portraits have begun appearing in the arrays on his walls.

History, for this history major, has become multiple: there are parallel histories on his walls, floors, and ceilings. One history is that of the Pawnees: their understanding of their own times and history is played out in the house through maps and icons, references to certain powerful shapes, directions, colors, animals. A parallel history is that of the new nation that encompassed the Pawnees, represented in the person of such explorers as Zebulon Pike, a solitary observer who mapped new ground over mountains. Still another thread is art history: the story of how artists have perceived what lay around them and depicted it; the history of literature is yet another parallel tale, as is personal history and sports history.

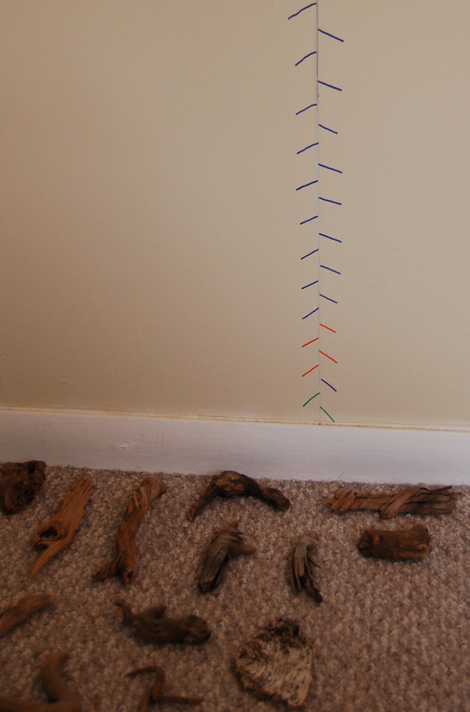

The house contains all of this, arranged in ways that make the points of contact, both actual and virtual, of all these streams of causality visible to one who is seeking them. You walk into the entryway, and there is one passage to the basement that contains artifacts from several of these streams — driftwood arrays, small color icons, and Twins images — that will lead into rooms in which still more such assemblages proliferate, along with images of skiers and a rug made of the blue denim clothing that Oman has discarded through the years.

______________________________________________________

These carefully selected objects and magazine clippings serve like the portkeys in a Harry Potter book — they open doors to realms of experience that are proximate to the books near them.

______________________________________________________

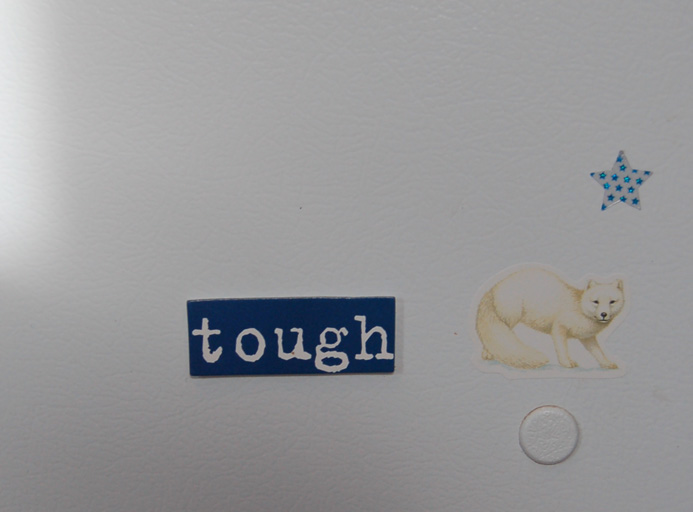

A second passage from the entryway leads into the kitchen, where the same indigo blue covers cabinets ornamented with a few foreign coins with images of animals. Small images of wild animals (polar bears, wolves) and cosmological and color icons (suns, red and blue forms) are also found, in locations that speak a dialogue between being hidden and being found (things cannot be “found” without being in some way displaced — hidden in a way, though often in plain sight).

From there, the living room contains a cage that houses certain rocks, as if animate; skis flanking the doors like columns; images of important landscapes and abstract wax paintings Oman has done. The next room contains shelves of selected books, prints of artworks cut from art magazines, a giant Joe Maurer photo, and carefully selected objects that serve like the portkeys in a Harry Potter book — they open doors to realms of experience that are proximate to say, the books near them. And up the stairs to bedrooms, similar morphing arrays proliferate.

How is this non-cluttered, austere but highly charged realm of symbolized thought different from any other house, with its souvenirs, texts, images? Most houses are repositories, but they are somewhat thoughtless repositories, filled with stuff that has washed up on the beach of experience, so to speak, and has no necessary connection to the house or its other contents. This house, though, is all thought. No image or book within it is random. Nothing is capricious. Or, rather, if something finds a spot in this both antic and disciplined assemblage, that thing locks into its place of residence like a molecule into a complex compound, and forms part of the thought process that the array facilitates.

Matt Oman now says that the house is done, that it’s complete. I would hope that the contents will continue to evolve, to shed and add materialized thought and become, over time, different. It’s a fascinating project. Experiencing it made my own random hoarding seem irresponsible, in the light of a materiality that is all function, and a function that dematerializes stuff and turns it into idea. What a concept!

______________________________________________________

See Matt Oman’s “memory palace” for yourself in the extensive slideshow at the top of the page >>

______________________________________________________

About the author: Ann Klefstad is an artist and writer in Duluth.