The Frisson of an Unfamiliar World

On the phenomena of uncanniness—also known as frisson, or the aesthetic chills that bring goosebumps to your skin—and what resonance might emerge in the spaces between objects

Uncanniness—you know it—“the strangely familiar or familiarly strange.”1 It follows us day to day, repetitions of things we are familiar with saturating all the unknown spaces. Our minds fill the gaps of our world with the recognizable even when it doesn’t quite fit there, creating phantom wormholes, unanticipated mystery, and weird glitches in reality. “Uncanny” is used as an English translation of the German word unheimlich, which means the opposite of everything homelike, familiar, intimate, and friendly. More so, unheimlich “is the name for everything that ought to have remained…hidden and secret and has become visible…to veil the divine.”2 Might we interpret divine here to mean of another dimension, an expanse greater than our vision, an unquenchable mystery?

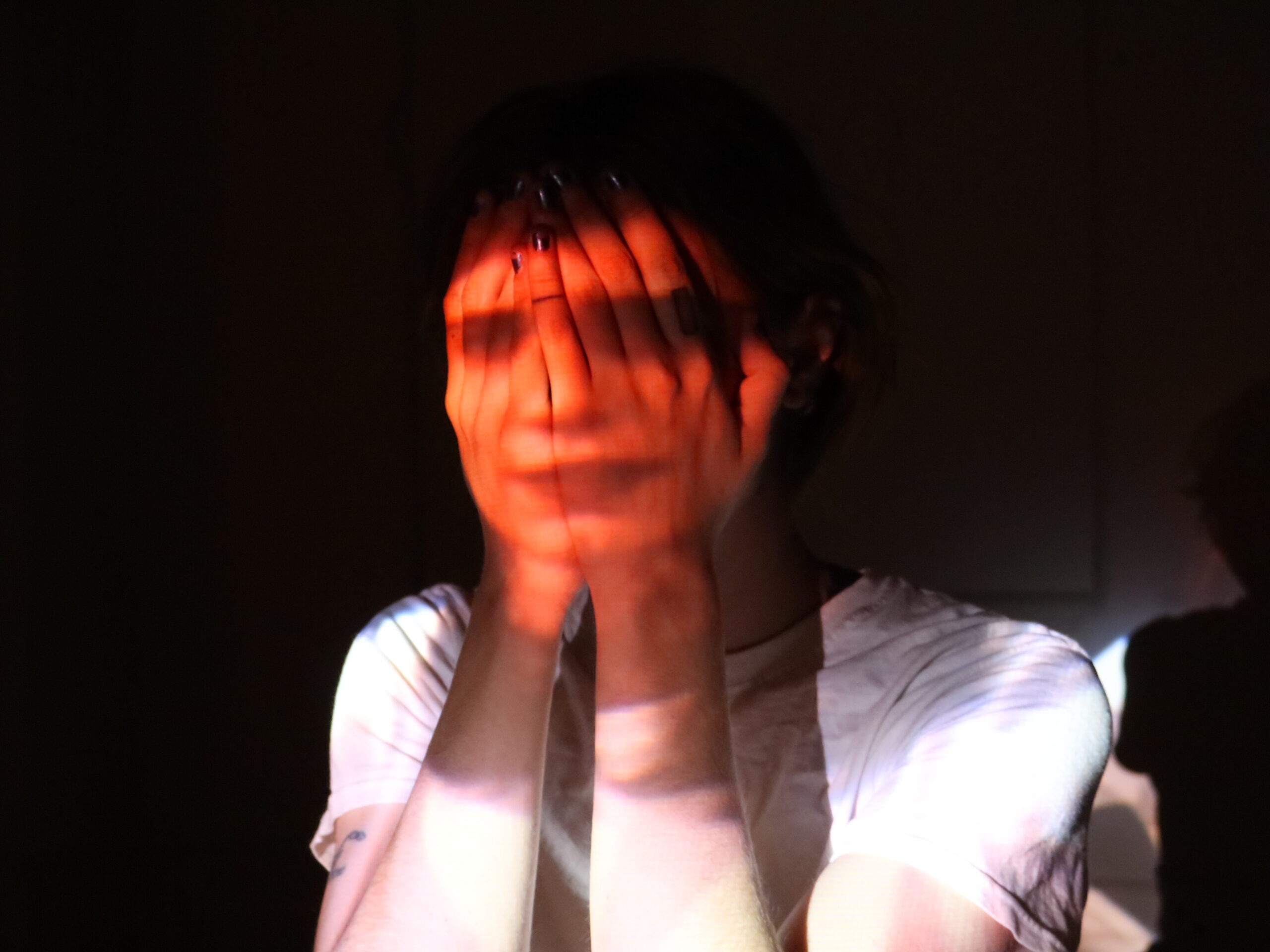

A body stands in the space. It is dark except for another body, a projection, ephemerally caught on a mesh curtain. The two identical bodies see each other and move nearer. The projector wheezes in exhaustion. When the live body reaches out to the projection of itself, the hand of the projection catches on its own hand, schisming from its respective arm. The bodies continue to curiously interact, gesturally catching bits and pieces of each other onto themselves: faces on palms, jawlines interlacing, entangling in glitched choreography back and forth through one another.

Goosebumps, ears pricked, a tingling in your head, the metallic taste of a dropped stomach, and a hyper-aware openness in your chest. The phenomena of uncanniness are also called aesthetic chills or frisson—chills which are experienced from the “fear-inducing or awe-inspiring.”3 You’ll be familiar with them in hearing the sweeping harmonic change of an operatic aria or in the concluding line of a poem spoken out loud. Aesthetic chills hit you only for a moment. You can listen to that part of the song over and over, but it was the realization of something previously unknown that created the sensation zinging through your body. Uncanniness and artistic expression both trigger an expanded understanding of the world, an expansiveness that can only ever be glimpsed. For example:

You’re in your bedroom. It’s dark and quiet. But you see, suddenly, out of the corner of your eye, a glowing white figure flicker across the room. You freeze and the hairs stand up on the back of your neck. You realize that it was actually a light cast through the sheer curtains onto the wall from a car passing by the window. Simple things like headlights and curtains and walls are familiar, very of this world, but for a moment you saw past the bedroom and into an eternal realm of ghosts and spirits. For a moment, the world expanded and this expansion rubbed up against your body, shivered down your spine.

In a moment of altered perception, we experience things that are half a world away, or gone from the living—things that exist in a different realm. In the experience of frisson, operatic voices and mysteriously blurred forms literally exist within the goosebumps on your skin. This is the vastness of the universe infiltrating us; the realization of its sudden nearness quivers in our bodies intimately.

As the name suggests, those spooky, eerie chills are an aesthetic phenomenon, “in the strict sense that aesthetics has to do with the way one object impinges on another one.”4 For context, an object is any thing—as books and bowls are things, but also, as you could refer to really anything as a thing, such as god, or a relationship, or capitalism, or an unknown piece of trash. Aesthetics is the resonance that exists in the spaces between objects, like the dissonance of harmonics reverberating. It is the familiarity between things, their kinship, their affinity. In composition, the “arrangement of things is not just an aesthetic expression: it is a communicational act”5 where stuff happens in the dialogue of things, in the dialogue of headlights and curtains and walls—or more poignantly, the dialogue between distant realms and our intimate body. All objects exist in relation to each other in a “thick present,”6 an ecology where boundaries are thinned and all objects enmesh. We can think about this in the way that dirt gathers on our feet as we walk barefoot and leave footprints.

In the field of philosophy that I am referencing, Object-Oriented Ontology, we begin to deal with things in the world existing in their own autonomous right. Before OOO’s inception around 1999 by Graham Harman, ontologists widely thought of objects existing because of “man’s” perception of them. Although perception is what allows us to locate ourselves within all the many objects around us, OOO believes that all objects are perceiving each other, and that this interpretive action is not exclusive to humans. When we interact with objects, or objects interact with objects, they are perceived through the set of sensory tools that are offered to us by aesthetics. The aesthetic dimension could be pictured as a veil that sits between us and the glimmering structures of the deeper functioning of objects. This veil is what we interface with; it is the sensual profile of everything, glossy, slimy, rough. Objects “can only affect each other in a strange region out in front of them, a region of traces and footprints.”7 In this sense, aesthetics are a place where things only appear through their effect on other things, hence, “the aesthetic dimension is the causal dimension”8, as in cause and effect. The uncanny exists in that aesthetic space of causality, in the space where objects act upon each other in their strange and mysterious interconnections, where mirages of objects reflect off other objects, and ghosts of things emerge momentarily from the veil. From there, it becomes clear that the only way to fully interrogate uncanniness is through aesthetic practices. Live art, as a practice of active image making, grabs hold of the veil and twists it up, wrenches water out of it and plays in the puddles left on the floor.

In Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto,” she discusses the cyborg as a composition of self and other, an embodiment of the dialogue between things. She explains that a cyborg is “simultaneously animal and machine, who populates worlds ambiguously natural and crafted,”9 replicating and representing humanity through different mediums. The fictional icon of cyborg straddles the borders of human and non-human, living and dead, fiction and reality, on this side and that side of the veil. Between all things, it is a body full of tension and contradiction. With a lack of labels and predetermined borders that govern our bodies (and so too the objects that we interact with) cyborgs represent “pleasure in the confusion of boundaries and…responsibility in their construction.”10 While this concept can extend to many sociopolitical issues, Haraway speaks particularly about queerness and post-gender politics.

I decided to use cyborg theory from Haraway’s manifesto as a framework for live art. In my performance work described earlier, By the Glimmer of a Half-Extinguished Light, I used three radios to make a theremin, an instrument that the player doesn’t touch, but uses the proximity of their hand to the antennae to play the electromagnetic waves. The sound comes through the radio, a sort of high-pitched frequency that sounds eerily like a wavering operatic human voice. Like the gap between live and projected body where new, strange forms get caught, it is in this gap between metal and flesh that a new voice emerges, through the resonance and vibration of larger energetic structures between things. Making this instrument became a process of exposing that causal dimension through hybrid (cyborg) performance making practices.

Masahiro Mori’s Uncanny Valley11 gives context for the experiential eeriness that comes with organic or technological hybridity. When we encounter something that is very aesthetically similar to us but is then revealed to be not-human, our initial affinity or kinship to the thing is broken and our sense of comfort is momentarily shattered. On the other hand, things that look less similar to us but then show similarities over time do not give us that same eerie feeling of being displaced, as we never relied on that initial kinship. Mori gives examples such as modern AI robots that so closely (but very disturbingly) mimic our behaviors and gestures at lagging speed, or zombies who take our form but twist it into a threatening and hijacked version of liveness.

Now, in the Anthropocene (a geological epoch defined by the dominance of human impact) we can see industrialization change the face of the earth, pushing us further into this “ambiguously natural and crafted” world that the cyborg emerges from. I noticed this particularly when I lived in Scotland—the forests grow in precisely ordered rows, all of the trees the same height, the same thickness. Each one almost exactly the same as the last. I wondered what kind of natural phenomenon would make the trees grow in this way, perhaps something to do with the light that gets through the canopy. The actual reason was that only 1% of the native forests remain, and that the trees grow this way because of how they were replanted. In this way, the forests became somewhat eerie—a strange version of nature that reflected our impact back to me. Anthropologist Lynn Meskell says that “everything that we are and do arises out of the reflection upon ourselves given by the mirror image of the process by which we create form and are created by this same process.”12 The world becomes a landscape of not-natural-enough, dipping deep into the uncanny valley—a mimicking version of how it once was. As Mori dissects, the further our aesthetic experiences dip into the uncanny valley, the more frisson we experience. As this frisson comes from the impinging of one object onto another, we can understand through it not just expansion and interconnectedness, but also tension, power imbalance, oppression, exploitation, and subjugation. The Anthropocene itself has entirely shifted our collective experience of relation, and become fraught with these threats.

Live art, emerging only a decade or two after this change in epoch, deals directly with objects in a way that not only deconstructs our relation to the world around us in a postmodern, self-reflexive way, but reperforms (inter)action to subvert previously accepted interpretations of relation. We could go into a rabbit hole here discussing how performance itself is a “twice-behaved behavior”13, or how contemporary art has a specific obsession with repetition. How many layers of mediation can be created? Are these processes only available to us due to systems of mass production? Does it become an uncanny representation of uncanniness? How meta does it go? Is this helpful? I’m not sure. Moving forward:

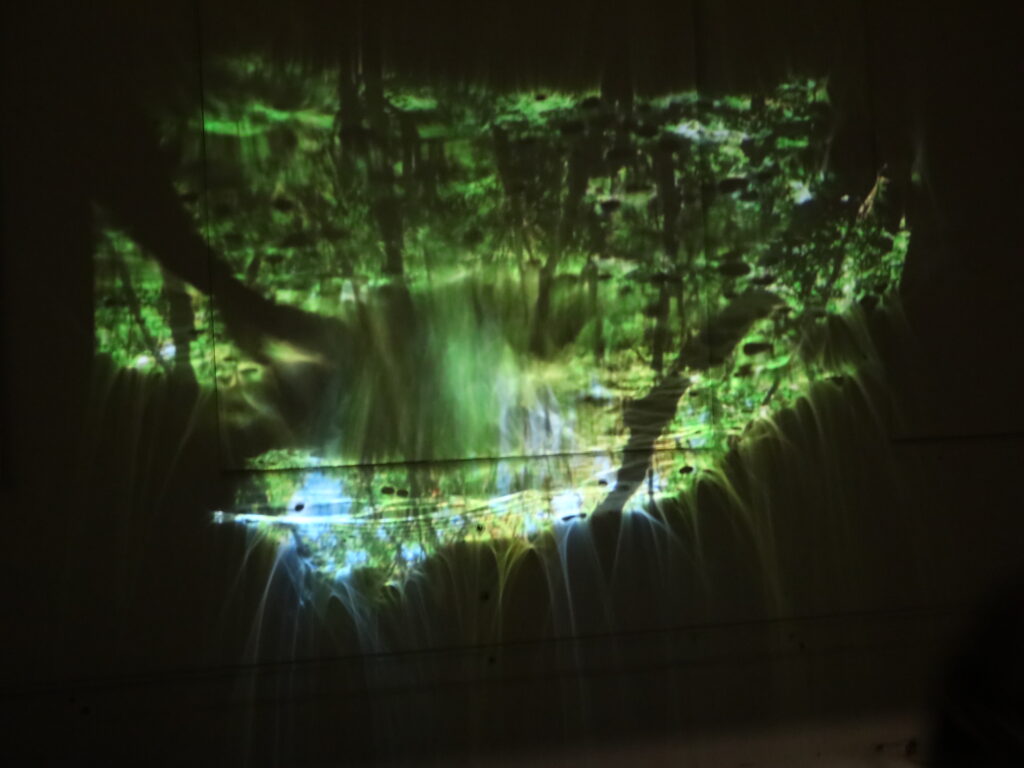

A pool of water is poured onto the floor. At a low angle, a projection of a forest hits the surface of the water and bounces back up to the wall behind it. Through the water the image expands, creating an entire landscape—a portal that does not bend to the corners of the room, and is instead superimposed on this space, ethereally floating between here and there. The forest is only light, and is framed by the ragged edges where the water runs out. This forest is manipulated by the performer communing with the water on the floor. By interacting with the water, by getting their hands wet, their hair, their arms, the reflected image of the forest quivers and ripples, dispersing and redistributing into new forms. The smallest of their actions shakes the illuminated trees, revealing the definition of the uncanny “as something which ought to have been kept concealed but which has nevertheless come to light.”14

As much as this gesture can be analyzed as perpetuating oppressive action, I offer here that we might be able to engage with this agency as a way to create something new, something better—and live art as a space to subvert static discourses and reframe action. Rather than understanding things to be submerged by other things, what if we understood them as emerging? Uncanniness—in letting us peek through the veil—allows us to see what has already passed and what is approaching. This sense of emergence appears in the experience of frisson, in that “chills elicited through these processes are linked to mechanisms of anticipation and expectancy,”15 a weighted motion towards something. I believe emergence comes hand in hand with the threat of submergence—it’s that “fear-inducing or awe-inspiring” dichotomy. In the causal dimension, they always exist in the face of one another.

Haraway writes in her discussion of cyborgs that “liberation rests on the construction of the consciousness, the imaginative apprehension, of oppression, and so of possibility.”16 The glimpse-able expansiveness of uncanniness offers us a momentary vision of what we can move towards. In this way, “the gap becomes not merely a tragic shortcoming of human perceptual limitations but also, fortuitously, a space of opportunity for the human imagination”17—allowing us to create new futures that exist now only as whispers, flickers, and shadows glimmering within our reality.