The Fringe: Beginning, Middle, Without End

Jaime Kleiman does a history and preview of the Fringe Festival, upcoming this summer. Stay tuned to mnartists.org for coverage of the Fringe in all its colorful multiculti glory--we'll be running news about the shows and lots of reviews as it develops.

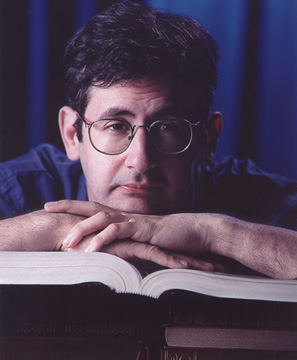

In its first three years, the Minnesota Fringe Festival plagued Minneapolis like a bratty cousin, at times amusing, at times whiny and uncontrollable, but overall easy to ignore. The shows were few in number, their quality was spotty, and it was all over within a relatively painless week and a half. Then a funny thing happened. In 1995, founder Bob McFadden handed the reins of the Festival to an ambitious man named Dean Seal. As Executive Director, Seal ushered the Fringe into its sultry adolescence – managing the Festival from his dingy basement office with some friends and a pad of paper. The history of the Minnesota Fringe Festival, much like the event itself, is larger-than-life, almost epic, and it smacks of raw ambition, human folly, and the inevitable fall of man.

The fall came when Seal got dropped on his head shooting a television commercial. He hasn’t been quite the same since. For example, he has trouble recalling exact dates. But the relevant numbers he can roll out like Swiss clockwork – and they speak for themselves. “The first year [with McFadden as executive director], we were at 4,400 [audience members]; the second was 6,000, then 4,400, then 4,400 [people],” Seal told me over coffee, the hint of a smile playing on his lips. “When I took over in the fifth year, we got over 6,600 people – that’s a 50% increase. I also introduced the Fringe Pass [what is now called the UltraPass]. But the next year was the biggie.” A biggie, indeed. The sixth annual Minnesota Fringe Festival had a 135% leap in attendance, numbering approximately 15,333 people. That’s the current record for audience percentage increase in the Canadian Association of Fringe Festivals – “a record that will probably never be broken,” recollects Seal, quietly and proudly, an Icarus still in love with his attempt at flight.

It’s impossible to talk about the Minnesota Fringe without mentioning Seal. Under his enterprising tutelage, the Fest grew exponentially, gaining notoriety as well as staying power. “The eighth was my favorite year – ‘The Fringe That Ate Minnesota.’ We had themes back then. It was a marketing thing.” Seal is, if nothing else, an excellent pitchman. The 8th Fringe broke his goal for a “critical mass” at 20,000 people, demonstrating for the first time “what the Fringe was supposed to look like.” The next year, 2001, at a record 30,000 attendees, Dean Seal stepped down, relinquishing his apoplectic position as executive director to focus on a slew of health problems that may or may have been caused by the stress of running the Fringe.

Referring to the next (and current) stage of the Fringe’s maturation, he says, “In any start-up, you have three phases: the Founder, who is the idea man [McFadden]; the Entrepreneur, who locates revenue [Seal]; and the Administrator, who nails down the process and gets the organization from the red into the black,” Seal told me, elucidating the travails of the Fest’s fledgling years – the quest for $10,000 so he could both run the Fringe and pay his rent, living month to month while urgently calling every person he knew and begging for money. “The more shows we produced, the more we money we lost, but [I knew that at] 20,000 [people], the marketing people would be interested. So I tried to make it as big as possible.”

Eleven years since its inception, and only four years after Seal’s passing of the torch, the Minnesota Fringe Festival has come a long way; it may not be “as big as possible,” but it is massive – the largest Fringe Festival in North America. And unlike the chaos of its early years, the “happy annual accident” (according to Pioneer Press critic Dominic Papatola in 2002) has now multiplied into an organized institution, complete with a full staff, a board of directors, corporate sponsors, and a reputation among Minnesotans as THE place to see edgy, quirky, and exciting new theatre. Leah Cooper, the current Executive Director, can be credited with many of these administrative shifts, as well as having conquered Seal’s unwitting departing gift of $50,000 in debt. Last year, Fringe producers got slapped with a percentage cut in their box office payout (from 70% to 65%), and audience members had to buy Fringe buttons in order to see the shows. Everyone was encouraged non-stop to “donate to the Fringe.” Say what you will about the methods, but her strategy worked: the 2003 MN Fringe Festival ended its year in the black, for the first time since…well, for the first time ever.

Cooper is responsible for keeping The Fringe true to its roots, even as it aims to become a significant cultural landmark and tourist attraction. It has remained an egalitarian beast – all producers pay the same application fee, and the selection process is brazenly random. “This year we got 193 applications for 160 slots. I literally threw them in the air in my office and picked them up off the floor. It was really fun,” said Cooper, whose penchant for quick speech reflects her let’s-get-it-done-now! attitude.

This unorthodox selection process is a testament to the Fringe’s non-juried credo, which sets it apart from other comparably-sized festivals in the United States, such as the New York International Fringe Festival, which is a partially juried event, and therefore, according to a somewhat disgusted Seal, “NOT a Fringe!” According to the Canadian Association of Fringe Festivals (of which Minnesota is a member), all Fringes must be non-juried, and adhere to “the main principles [of Edmonton’s Festival, which] was to provide all artists, emerging and established, with the opportunity to produce their play no matter the content, form or style, and to make the event as affordable and accessible as possible for the members of the community.”

It is a philosophy that Cooper guards with an almost mythic zeal. “We succeed at getting non-theatre people to shows and regular theatre-goers to cross over to different genres. We love calling everything performance. We want to eliminate boundaries about what theatre is.”

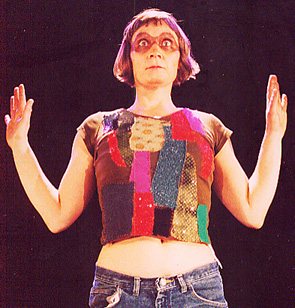

This year there will some old standbys, like story-teller/playwright Kevin Kling, funnyman Ari Hoptman, performance artist Heidi Arneson, and the Scrimshaw Brothers’ “Look Ma, No Pants” variety show. There will also be a slew of new producers. For some, it will be their first show ever. Cooper thinks that there will be more comedy than last year, and “a lot of political content…some themes seem to be emerging: politics, lies, and racism – it’s an election year, after all.” But can she tell us what to go see? “I can guarantee you that some shows will suck. That’s why you have to see at least three. Then you have to go to the Beer Tent in Loring Park and talk about them!” Like Seal, Cooper has a good mind for sales and an unlimited belief in the power of guerilla marketing. Seal and Cooper both believe that a good show doesn’t need to spend a lot on advertising – if a show is good, people will hear about it. The converse is also true, by the way – a strong opening night can have an adverse effect if a show doesn’t live up to its hype.

“So much of the Fringe is about buzz, and every other Fringe has a central meeting place. So we created a tent called ‘Fringe Central;’ it’ll be a gathering place where audience members can meet artists, watch sneak previews, buy tickets, post reviews online, and talk about the shows they’ve seen.” There will also be “fringey” singer-songwriters and music, food and beer, and incessant hob-nobbing among producers. The Fringe may be oversized, but Minneapolis is pretty small, and the best way to get people to your show is by word of mouth. The tent is one more way of building community and encouraging Fringers to discuss shows.

Other innovations this year include the Fast Fringe (five new 10-minute plays by local playwrights), the Digital Fringe (shorts presented on the website throughout the festival), the Kids’ Fringe (all shows by, about, or for children), Stand-Up Fringe (bring your own tomatoes), the Spoken Word Fringe (in a theatre instead of a coffee shop), and a Visual Arts Fringe – presented in galleries for the first time. Overwhelmed? You could simply buy an UltraPass, which’ll give you unlimited shows for $100. The Festival’s website (www.fringefestival.org) will help you with all your scheduling needs as well as provide access to audience reviews, festival blogs, the Digital Fringe, and links to other Festivals.

“The Fringe exists to break boundaries and create a space for artists without resources,” says Cooper. “ And it excels at diversity in styles of performance.” This year the Festival is stretching to more fully embrace that concept. “My long-term goal for the Festival is to expand – not the number of shows, but to provide more venues for different forms of art. I imagine a Music Fringe, a Visual Fringe, a site-specific performance art festival, a real art crawl.” In Cooper’s not-yet-realized world, Minneapolis is a city defined by its cultural institutions, not its malls. “If you keep starving artists, they’ll live, but it will mean the death of the small theatre, like Chicago or San Francisco. We’re the only Fringe in North America with no state or city financing.” When asked if maybe the Fringe has outgrown itself, Seal’s opinion mirrors Cooper’s. “I don’t think the Fringe is too big. It’s a major cultural attraction for Minnesota and should be subsidized.”

For an event that has become a “lasting landmark on Minnesota’s cultural scene.” (Papatola again), the lack of public funding seems ridiculous, at the very least severely misguided. “It would be nice if we had a society wherein corporate culture felt compelled to volunteer and contribute,” stated Cooper, matter-of-factly. “The city and the state need to realize that small to mid-size groups make Minneapolis better…people who work for non-profits should get a tax cut or something.” Cooper then stated, “Even a mediocre nonprofit is probably being run by a sharper, more creative staff than a for-profit. I don’t know what the right [business] model is, but you have to make decisions – hopefully well – and live with the repercussions. We’ll keep embracing diversity and make room for everyone.”

Hopefully the Fringe Festival, like wine, cheese, and rambunctious teenagers, will age gracefully and expand under the auspices of state funding, rather than collapsing under its apotheosis. In true tragic form, the ascension of the Fringe could one day be put in a perilous position. So head on out to that corporate beer tent. You might meet some interesting people, see some great shows, and be inspired to create your own, all the while helping support artists who care passionately about creation and don’t give a damn about commercialism. Which is exactly as it should be.