The Exuberance of Young Dance

Ballet, like many classical arts, begins with form, discipline, steps - not improvisational play and feeling. And authority comes later so much later that most students (and many professionals) never get there. Not so with Young Dance.

A FEW MONTHS AGO, HEARING I WAS A DANCE CRITIC, a woman asked me to recommend a dance school for her daughter—“somewhere that won’t give her a messed-up body image,” she added. This question came on the heels of another—where in town could she go for good ballet? She asked that last with a bit of a sigh that implied she didn’t want to muster up cheers for hard-working hometown scrubs; she wanted to sink into the real deal, flawless and willowy classical sylphs. Together, the two questions piqued me: What?, I wanted to ask; Eating disorders are fine for other people, just not for your daughter? I don’t remember how I answered her question, but I wanted to say something like this: “Just send her to ballet class. Sure, she’ll get screwed up, but everyone does, and at least ballet, like Catholicism, is an interesting screwing-up — one with history, beauty, discipline, ideas.”

That’s the answer I would have liked to give a few months ago, anyway. But I’m not sure what I would say now—now that I’ve seen Young Dance.

Saturday afternoon, Young Dance takes over the unused rooms in the Hennepin Center for the Arts. Where should I go? They’re upstairs, on seven, they’re downstairs on two, they’re on some floors in between as well. I head for seven, where Justin Jones is teaching a warm-up to the younger kids (seven to eleven or so), with Brian Evans accompanying on the piano. Jones leads the kids through a series of s-curves, dipping to this side and that, then forward and back, trying to get them to feel the head’s weight sitting on the spine like a poppy bud on a flexible stem. This is a difficult exercise, demanding a silky coordination and freedom, and the kids (despite the stereotype of kids as instinctual movers) have trouble; one girl cracks herself up as she tries to lead with her head instead of her neck. “The way I do it might not be the way you do it,” Jones encourages them. Despite the difficulty, they’re mostly game, especially when Jones gives them a two-minute space to improvise on the feeling. One little guy bops around, forgetting his mobile spine and instead tossing out twitches and sudden reorientations, incipient breakdance moves. One girl who paid almost no attention to the exercise before throws herself into the improv, ending up ten feet away from where she started. A girl in a wheelchair holds hands with another girl, feeling the dance through her, her own dance subtle and angular. Most of the kids wobble around like snakes tasting the air. There’s no wrong answer. Almost toppling over, Jones comments, “My head took me off balance. Sometimes that’s really fun.”

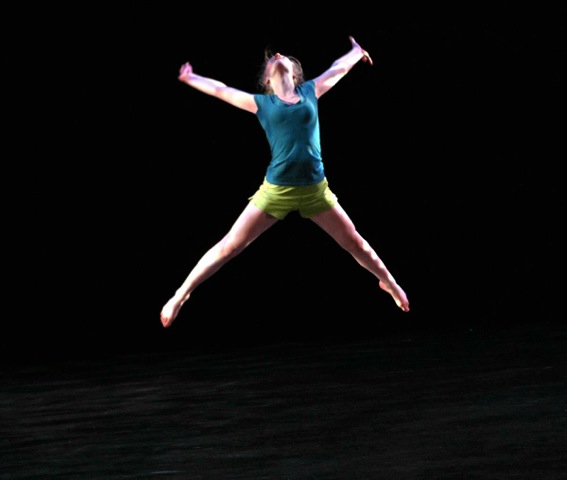

I’ve never seen kids trying to do an exercise like this. When I say this to Jones later, he says, “Thanks.” He goes on, “If this had been around when I was a kid. . .” Young Dance, celebrating 25 years this year, is not a typical dance school. For one thing, Young Dance concentrates on dance as expression and art rather than discipline and technique. For another, it has no building, instead borrowing and sharing space around town. And its student dance company (about thirty-five kids, ages 7-18, selected at audition for desire to dance rather than technical skill) works with professional dance artists like Jones, Evans, Patrick Scully, and BodyCartography, as well as professional artists in other disciplines. Altogether, Young Dance proposes an entirely different experience by way of dance education.

After the warm-up ends, everyone troops downstairs to big studio 2B, where I take ballet class during the week. Here Jones rehearses with the little kids on one side of the room while Evans coaches the high school dancers on the other side. Evans’s group (diverse in appearance and ability) is working on the concept of risk, thinking together about what might come across to an audience as a risk. “That doesn’t seem risky, that seems cliché. Explode and fall down? Come on!” one exclaims. Evans suggests a lift, watches it. “Now that’s risky,” he comments. “Bad idea.” Instead, they decide to create a series of lifts, one after the other, starting with one girl lifting one other girl and adding on until the entire group lifts the last dancer.

______________________________________________________

I have mixed feelings: It’s impossible not to enjoy and admire what’s happening here, but I miss the cruelty of art—the heartbreak of understanding and being unable, moments of ecstasy, the rarefied air of a classical form.

______________________________________________________

Should I point out that this doesn’t happen in your usual youth ballet class or rehearsal? Partnering class, when it’s available, is fairly codified, and rehearsal rarely turns into improv. People invent moves, sure, but on their own time. And working from a concept—creating a structure, then letting steps fill in—you don’t do that in your typical youth ballet.

But adult dancers in ballet or other forms do this frequently, with some companies and choreographers rely almost completely on the kind of invention that’s happening here. I know James Sewell Ballet spends chunks of time in what Sewell calls “research and development,” which his dancers call “play.” It’s just that ballet, like many classical arts, traditionally begins with form, discipline, steps, not composition structure, ideas, feeling. Or, to put it another way, what student dancers work at first is the appearance. Authority comes later—so much later that most students (and many professionals) never get there.

One girl jogs towards the group. She seems shy of throwing herself at the others (she’s not small), so Evans runs her lift over until she’s confident. It takes courage to jump and strength to catch—risk, trust. “Take care of each other,” Evans says. Jones and Evans both project a happy confidence that kids are not made of glass, mistakes are fine, everyone is well-intentioned, and dance is fun—which is invaluable for the potential bedlam they’re presiding over. After Evans’s group has got their lifts down, another group of high school students who’ve been quietly reconstructing or creating a dance phrase in the back come forward to teach their phrase, with infinite patience, to half of Jones’s little kids. The other half, let loose, go flying around the room like helium balloons.

I have mixed feelings about all this. On the one hand, it’s impossible not to enjoy and admire what’s happening here. On the other, I miss the cruelty of art. I don’t know what else to call it—the heartbreak of understanding and being unable, moments of ecstasy, the rarefied air of a classical form. Am I just nostalgic for my own screwing-up? Maybe. It’s hard for me to imagine a dance education without tears.

But it’s not as if ballet is incompatible with Young Dance. Several of the high school students attend Saint Paul Conservatory for Performing Artists, and I catch a few girls trying out ballet moves in the mirror. And I have to acknowledge my own increasing dissatisfaction with ballet education and my feeling, as I watch very accomplished young people soar through the air in ballet class, that I’m not seeing art there either. If I would still tell any would-be dancer to learn a classical form (not necessarily ballet), I might also encourage them, now, to seek out training like this.

Dance class isn’t all about dance, anyway. Evans’s teenagers are now sharing their lifts with kids just a little younger than them, pre-teens. They’re doing blind falls: you tip over backwards, without looking, and the person behind you catches you under the arms and bounces you back up. I watch one girl’s face: thought and worry as she topples, then absolute bliss as the older girl behind her catches her. “Again!” shouts the older girl: the older girl, who I imagine this younger girl looks up to so much. Fall, catch; risk, delight.

______________________________________________________

Related links and information:

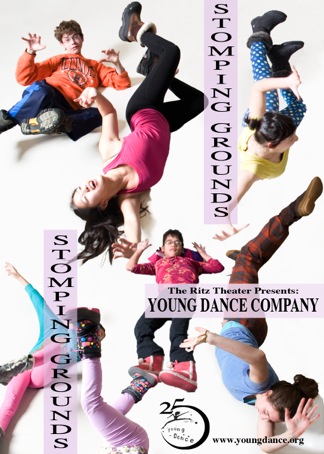

Young Dance celebrates its 25th with a gala on May 3 at the Ritz, featuring guest speaker Kevin Kling and live music by Dean Magraw, and performances by Young Dance, alumni and past artistic directors. Their annual concert, Stomping Grounds, runs May 2-4, also at the Ritz. Find out about summer programs and classes, upcoming performances and events on the company’s website. The next auditions for the company are coming up May 28 at 4 p.m.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl was recently published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She writes a weekly column on dance for mnartists.org.