Roshan Ganu: Language and Illusion

A conversation with the 2022/23 MCAD–Jerome Fellow on experimental translations, longing and belonging, and the emotions held by materials

Yuanrong LiYour interdisciplinary practice is a combination of personal and cultural influences. How does your Goan upbringing and experiences as an immigrant influence your work?

Roshan GanuFor somebody from Goa, this question might mean something different than for somebody from here. Even within Goa, there is nuance in the experience of the place, just like there is tremendous nuance in the immigrant experience. When I respond to my Goan upbringing I am conscious of the multilayered, multilingual, and multicultural experience I’ve had of the place, which might not be the same for someone who has five generations of personal history growing up in Goa. My interdisciplinary work comes from this space of being transplanted. I’m seeking belonging in a new environment while being confronted with unfamiliar spaces. It is an emotional journey navigating this changing landscape. I am in the process of building a sense of place and understanding my relationship to this geography, nature, astronomy, and our communal place in the contemporary world.

YLCan you speak about your use of multiple languages in your art and how it contributes to your conceptual framework?

RGFormal language is a means to our consciousness. But consciousness itself knows no formal language. I am interested in a transdisciplinary translation of concepts and the fluidity of our human experience. I speak and understand six languages: Marathi, Konkani, Hindi, English, French, and Portuguese. Each language ignites its own consciousness and in each language I understand myself differently. The immigrant experience complicates this by introducing a foreign context. I am interested in this interflow of meaning in a multilingual and multicultural framework.

YLI’m interested to learn more about the meaning behind the work चांदोबा : A Trip Into The Moon and the significance of the Marathi children’s poem that inspired it?

RGOver the past few years I’ve been observing the recurrence of a dialogue between my internal and external world. This conversation builds a relationship between the landscapes on both sides of this glass pane, which in turn instills in me a sense of belonging. I believe that this is an inherent part of the migrant experience. We continually impose memory and an alternate reality onto the present moment, until it becomes familiar and soft. In चांदोबा : A Trip Into The Moon I decided to exaggerate these landscapes into superlatives: internally as an unfulfilled longing and externally as outer space. Just like mythology does to existence, I chose to ground the work in a popular, memorable Marathi children’s poem that seduces these extremities while igniting a childhood song. All together, the work was an exploration of isolation as a state of mind: the melancholy, survival, the self, longing, calm, movement, water, the moon, illusion, reflection, object, and materiality.

YLIn उत्कंठा, you use neon and moving images to convey emotions. Can you talk about the process of creating this work and your thoughts behind not providing a translation for the Marathi word used?

RGउत्कंठा planted a seed in me that is still germinating to this day. It brought “language” to the forefront, but not in the linguistic way. Each language is a whole world, a whole consciousness. One understands themself differently in each language based on the sociopolitical, cultural, geographical, historical, ethnographical, scientific, artistic, imaginary, mundane contexts of the experience of that language. In this way, linguistics is merely one small window in a Hawa Mahal (“wind palace” that has hundreds of small windows to keep the palace cool, a fusion of Rajput and Mughal architecture). I am interested in transdisciplinary translation, experiential translation, language as consciousness. With an awareness of six languages, I have adapted language to build thought, belong, build relationships, rather than to impose. It’s okay to not know.

YLCan you discuss your use of materials, such as animation, neon, mirrors, handmade papier-mâché sculptures, and water, and how they contribute to the immersive, emotional, and aesthetic experiences in your installations?

RGI seek materials that can hold emotions and illusions, giving me freedom to maneuver worlds in space. Neon and mirrors are immersive to a level of dreaminess and trickery. Color is emotion. Water and reflection can be meditative, hypnotic, or destructive. Handmade papier-mâché sculptures foster nostalgia, vulnerability, and monumentalized memory. All these come together on stage through the school of thought called Cinema of Prayoga, which is an alternative to experimental and avant garde, but of which they can both be a part. Amrit Gangar, the creator of this thought, says, “Prayog is a Sanskrit word which could mean ‘experiment’ or ‘use’ or ‘put together’ or ‘design’ or ‘cause’ or ‘effect’ or ‘performance’ or ‘play’ or ‘representation’ or ‘practice’. So the Cinema of Prayoga can be a much wider, much deeper, notion than ‘experimental cinema’.” While I am still probing my place in the larger system of cinema through moving image and installation, Cinema of Prayoga lays emphasis on the collective, relational experience of the different elements in my work, rather than prolonged focus on their individual significance.

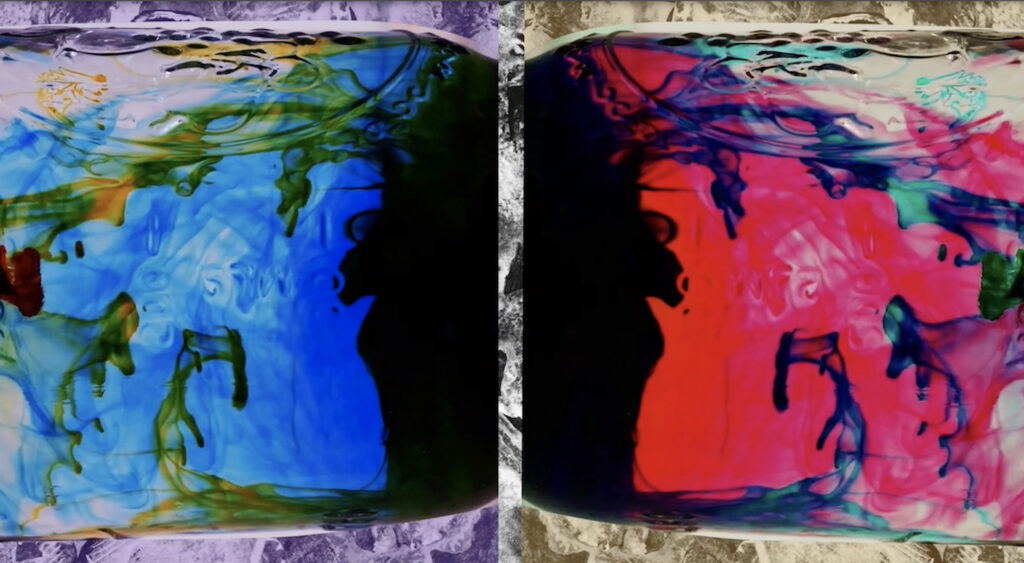

Roshan Ganu, Personification Of The Moon (चांदोबा), 2022.

Roshan Ganu, Cygnus Loop, 2023.

Roshan Ganu, Personification Of The Moon (चांदोबा), 2022.

YLYour work often touches on themes related to the human condition, can you tell us more about how you approach these themes and how you want the viewer to respond to them?

RGNot knowing, the obscure, the night, the limitless. It is terrifying and scares the daylights out of me. But I tug at it, is there a mashaal (torch) I can find? Is the darkness the mashaal? The human condition, for me, is grounded in the mundane, in relationships we build with nature, people, animals, song, spoken and written thought. During the deepest and darkest days of winter, a big feat for a tropical person whose oneness is with the sun, I turned the camera lens onto my interiority and started documenting these obscure spaces. I would film myself late into the night, alone, by the windows at my studio and outside, and the mundane would surprise me. I can go on about this process. But for my viewers, I would love for them to respond to my work with their time. By spending slow moving time, as much time as is available, and to be surprised and/or find their own place within my work.

YLHow has winning the Jerome Fellowship affected how you approach your work?

RGThe Jerome Fellowship means so much more than what we read on paper or on the website. Personally, for me, winning the Jerome means opportunity, institutional and financial support, a career push, a belief in my cause, a bright beacon to keep going, to up the game, to think big, to dream, to make things happen. It means a next step in my career, access to resources, studios, and equipment. So many things.

YLIf you could describe your work in one word, what would it be?

RGSlow, contemplative, open, liminal, poetic, limitless… They are all one word which is yet to be created.