The Colonial Logic of the Independent Artist

Emily Gastineau recaps a conversation on "Place, Race, Geography and Power" at the recent Hand in Glove conference and asks: For white-led organizations, how does your consumption of resources, your cultural voice impede someone else’s sovereignty?

At the panel titled “Place, Race, Geography, and Power” at this weekend’s Hand-in-Glove conference, the panelists and audience wrestled with the concept of ownership: its personal significance and its historical violence. Responding to moderator Chaun Webster’s prompt to discuss “defying colonial scripts”, Shawn(ta) Smith-Cruz spoke about her desire to own her own home in New York City. She stressed the practical and symbolic importance of ownership as a person of color because it greatly reduces the likelihood that she will be displaced by gentrification or discriminatory housing policies. Fellow panelist Dylan Miner, a Wiisaakodewinini (Métis) artist, activist and scholar, then weighed in on the overarching concept of ownership, proposing that the very idea of private property is violence. The panelists and the crowd fell on both sides of this fundamental question: Webster stressed the power of ownership for people whose ancestors did not own their own bodies, while an audience member argued that ownership seems like a band-aid on a huge wound, and racist laws can still result in the seizure of property. Webster agreed that ownership is “a strategy, not a solution”: a temporary, tactical move to reclaim power in the present, rather than a means to take down the system itself.

As a white artist, this conversation prompted me to examine what other types of colonial thinking might be present in the field of arts organizing. The artists and organizers of color on this panel strongly reflected their need to carve out spaces of self-determination within an oppressive system. By their nature, organizations founded and run by white artists enact a similar move towards self-determination—though from our different social location, it takes on a different significance. What do we mean when we call ourselves “independent” artists or “independent” art spaces? If we examine the funding streams, we see that even “alternative” and non-profit organizations are very much implicated in capitalism, benefiting from corporations and other bodies whose ideologies they oppose. For white people, I wonder to what extent the act of self-organizing mimics a colonial mentality, laying claim to space on a supposedly open frontier.

I’ve heard some language at Hand-in-Glove describing an “outside” to the system we find ourselves in, and the underlying assumption that we can strike out on our own to create a new or different space, separate from the status quo. If we think about it spatially, it is suspiciously like the colonial premise that there are always new frontiers, untouched places we can build from scratch, with resources we have the right to mine through hard work. The narrative of founding an artist organization, one’s own DIY space or autonomous project, is not so dissimilar from the “up by the bootstraps” American Dream myth. It includes the pleasure of being one’s own boss, and assumes a linear progression of history in which we move towards that which is new, different, better. Our actions imply that resources should follow with hard work and strong values, including the values of community interdependence and opposition to capitalism that I heard throughout the conference. As Miner also noted, capitalism has a way of bringing everything into its fold, including alternative cultural production. We tend to romanticize the “outside”, but I don’t think we should operate on the belief that it really exists.

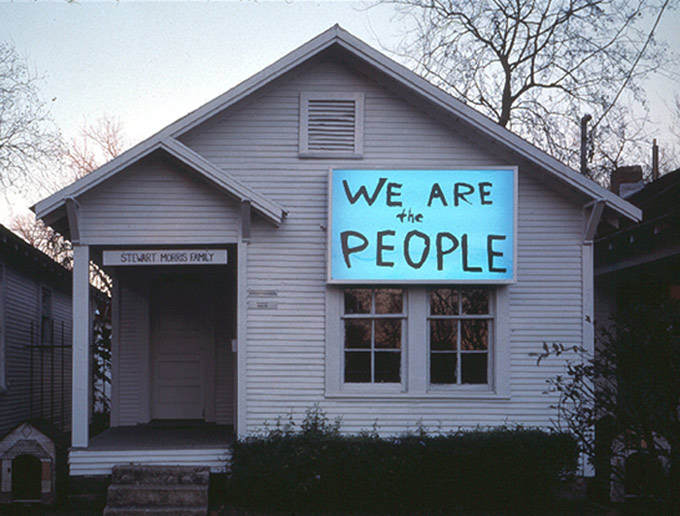

If we move from the spatial imagination to the spatial reality, we find that many autonomous projects headed by white people occupy space in low-income neighborhoods, with many people of color and indigenous residents—and thus contribute to the process of gentrification, no matter their tiny budgets or anticapitalist politics. (N.B.: I am personally implicated, having recently moved into a studio space in a mostly non-white neighborhood.) Most attendees of Hand-in-Glove seemed to be quite familiar with this cycle, but it demonstrates how white artists’ claims on autonomous work space contribute to the ongoing displacement of indigenous people and people of color. And in discursive space, when white artists found organizations dedicated to a particular type of work—whether it’s contemporary art, alternative practices, printmaking or performance—we tend to assume that our space should automatically cover all artists working in that realm, framing and claiming the work of artists of color within our own categories. For white-led organizations, how does your consumption of resources or your cultural voice impede someone else’s sovereignty?

Furthermore, when artists who carry racial and economic privilege “exit” the system in this way, is it an abdication of responsibility? Of course, white artists and organizers can experience oppression along axes other than race, and even well-connected arts organizations with privileged founders often experience financial hardship. As most everyone at the conference has experienced, artist-driven projects require massive time and energy to build from scratch and to fulfill the requirements of being a nonprofit. I wonder if the energy spent maintaining these sovereign positions, or the futile project of staying on the “outside,” distracts white artists and organizers from institutions where they might have greater effect. If we have greater access to the halls of power, and we profess our intent to change the system, why are we leaving to set up shop on our own?

I absolutely share the desire for my work to live “independently” rather than under the umbrella of institutions (note the word in my bio below). I am personally and professionally invested in the existence of artist-run spaces, and I believe they serve a vital cultural function by birthing artwork that is not primarily beholden to the marketplace. The panelists inspired me to follow their line of questioning, all the way to the very premise of the conference.

For white arts organizers: let’s continue to question our attachment to independence—what it means for us to claim it so easily, and at whose expense that occurs.

Conference information:

Hand in Glove 2015 (#HIG2015) took place September 17 – 20 at the Soap Factory in Minneapolis. For more information on topics, sessions, and related events, visit the convening’s website:hig2015.commonfield.org.

You can stream video of all the sessions online: http://livestream.com/commonfield/convening. Find more information online about Common Field.

Find more coverage of the 2015 convening on Mn Artists, mnartists.blog in the coming days and weeks, and read more essays — from conference participants, session hosts, and audiences on-site and online — in Temporary Art Review’s rolling “Hand in Glove Social Response.”

Emily Gastineau is an independent artist working in and beyond the fields of dance, performance, and criticism. She collaborates with Billy Mullaney under the name Fire Drill. They work along the disciplinary boundaries of dance, theater, and performance art, conducting experiments around the notion of contemporary and how performance art is meant to be watched. She is the co-founder of Criticism Exchange and Program Coordinator for Mn Artists.