The Audacity of the Solo

After Saburo Teshigawara's recent performance, "Miroku" at the Walker, Camille LeFevre examines the impetus behind a choreographer's desire to create a solo piece for him/herself, looking at the hubris, virtuosity, sheer endurance such a task requires.

WHAT COMPELS A CHOREOGRAPHER TO CREATE A PIECE FOR HIM OR HERSELF? What about doing so “accompanied” only by sound or music, lighting and the most minimalist staging? Such an endeavor requires adventurousness and supreme self-assurance to be sure, but there’s more to it than that. No small amounts of hubris and bravado also provide the impetus, as the solo is, more often than not, a showcase for virtuosity — usually of the physical kind.

Consider Molissa Fenley‘s solos from the late 1980s and early 1990s, such as her 40-minute State of Darkness, (which she performed at the Southern Theater some time ago). Fenley’s choreographic version of Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” for example, was a tour de force of sheer stamina, concentrated energy, and deeply sourced physical rigor. She performed bare-breasted and in black tights, surging through abstractions of innocence, fear, exultation, and deliverance in a performance of mythic sacrifice.

Conversely, for some Butoh artists, extreme stillness is their purview, captured through seemingly immutable explorations of the slow in time and space. These extreme versions of the solo came to mind during Japanese choreographer Saburo Teshigawara‘s performance last weekend of his 60-minute solo Miroku at the Walker Art Center. This, too, was a virtuosic display of physical stamina, articulated energy, and extreme rigor, as Teshigawara’s body shifted from shadowy stillness, balletic fluidity, gestural suppleness, and weightless grace to a lightning-fast scissoring of limbs, distorted musculature, and seizure-like phrasing through long periods jagged kineticism.

Imagine a Butoh artist schooled in ballet and manifesting the DNA of a break-dancer with pop-and-lock expertise. But such imaginings only begin to describe Teshigawara’s virtuosity. At times, he appeared almost post-human. A small man with a large veined head, narrow torso, thin whiplash arms, and peg-like limbs, he appeared at once ancient and youthful. His movements were, at times, robotic; his endurance was machine-like. And in his unearthly red shirt, he often glowed like Edward Kac’s transgenic, fluorescent bunny.

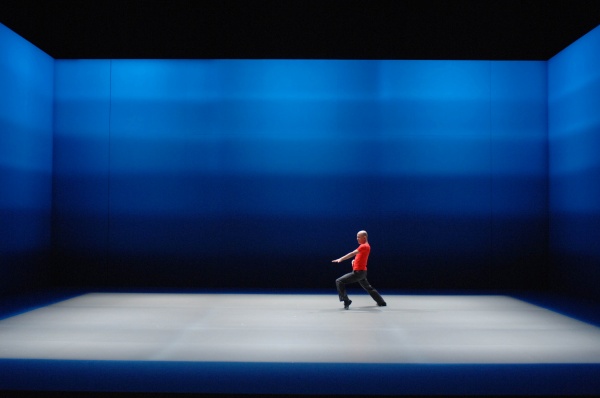

Miroku occurs on a set within the stage: a large, room-like box whose wall panels glow white, blue, grey, and blue-grey. When bathed in the greyest light, Teshigawara’s red shirt becomes a point of reference, a glowing ember among clouds. Bands of black, blue, and grey pulse across the walls; sometimes they appear as horizontal stripes, as in a Rothko painting; sometimes the colors frenetically run up and down behind Teshigawara and appear to crush him under their weight.

Bright rectangles of light periodically appear on the walls, like windows or escape hatches to an exterior world. Toward the end of the piece, Teshigawara handles a single lightbulb — displaying it like a penis, to illuminate his silent screaming, to conjure expressions of torture — while distorted rock music assaults the ears and bright white light blisters the retina, leaving afterimages of despair fading in the blackness.

In Japanese mythology, Miroku (also called Maitreya) is envisioned as the Buddha of the future, a savior to come. In the contemporary Japanese anime program InuYasha, Miroku is a Buddhist monk cursed with an “air void,” meaning he must be kept covered lest, as if he were a black hole, he pull in anything that passes by. Both interpretations of the figure “Miroku” resonate with the character Teshigawara enacts in his solo.

Teshigawara’s iteration is a creature in this time and yet not of it, with the self-confidence, nay hubris, to present the ugly beauty of his awe-full, sublime divinity, where fear and love co-mingle. His Miroku has to have the endurance of a saint to exist in the container of his own making; indeed, his Miroku expresses little interest in escape. For us in the audience, as with any long-form solo, our role is simply to witness virtuosity of the soloist’s performance. Our task is to attend to the physical and spiritual expressions of the work’s making, so that the soloist, despite his or her singularity, is never really alone.

Noted performance details:

In a joint presentation by the Walker Art Center and Northrop Dance at the University of Minnesota, Saburo Teshigawara/KARAS performed Miroku in the Walker’s McGuire Theater April 22 – 24.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Camille LeFevre is a dance critic and scholar, arts journalist and college professor.