Tender Regard and Comic Melancholy: Alec Soth at MIA

The Trialogue series at the Minneapolis Institute of Art features discussions between a critic, the artist, and the audience. Here's a transcript of Glenn Gordon's discussion of Alec Soth's show. Michael Fallon's take is next on the site.

I volunteered to be one of the critics in today’s Trialogue (together with Michael Fallon) because I am a photographer as well as a writer, and from the perspective of my own experience working as a photojournalist, there is much about the way Alec Soth approaches portraiture that I appreciate. I mean this not so much with respect to his command of camera technique, which is evident, but to his whole manner of handling the physically demanding and psychologically exacting ceremony of making pictures of other human beings.

I like the way Soth goes about things. He has a shrewd and sardonic eye, and he’s always alert to the unpredictable, nonstop strangeness of the world, but he rarely goes after weirdness for its own sake. He is sensitive to the currents that flow back and forth between himself and his subjects, subjects who, because of the time it takes to fiddle around and set up a shot with his large-format camera, cannot help but be aware of the thirst of his lens. In other words, in his encounter with his subjects he is always candidly a human being himself — he doesn’t use the camera to distance himself from other people.

If you’ve ever tried your hand at street photography, you may have some idea of the kind of logistical, social, and technical challenges Alec Soth encounters in the field. It’s one thing to sneak around shooting surreptitiously with a little rangefinder camera, stealing images like a purse snatcher, in the manner of Cartier-Bresson or Gary Winogrand. It’s another thing to show up on location with a tripod the size of a small giraffe and a camera that looks suspiciously like an accordion, conspicuously set this rig up, then put an executioner’s black hood over your head and try to get people to open up and cooperate with you.

I admire the way Soth risks and initiates direct human engagement, including living with the possibility that his approach and request to photograph a prospective subject might be rebuffed. Those who do consent to pose for him he engages head-on, more often than not photographing them standing full-length, head to toe. They aren’t caught off balance or taken by surprise. For the most part, his subjects stand there with a stolid and unembarrassed dignity, unsmiling, but essentially calm. They have agreed to the encounter and their consent to pose before Soth’s antique photographic apparatus lends a measured, nineteenth-century formality to the occasion even when the setting is casual and the photo is apparently candid, seeming almost a snapshot. Soth sometimes photographs people in pairs but most of his subjects here are solitary individuals, centered in the frame in singular and concentrated isolation. The formal, almost iconic stability of his portraits is a natural result of his methodical use of the large-format camera. The process, as I’ve said, is measured and deliberate, the furthest thing from point and shoot. His old 8 x 10 wooden view camera is a mahogany confessional. The camera’s bellows breathe in the sitters’ souls.

Photography is now a phenomenon so ubiquitous that most of the time when you’re doing it you aren’t conscious of just how amazing a thing it is, but when you take half a step back to think about it, the capture of the image of a human being is still an incredible transaction. It happens a million times a day, but it’s still incredible. Soth’s best pictures succeed in conveying this afresh, as though photography weren’t commonplace, but an astonishment invented only this morning.

For reasons I don’t completely understand, the pictures as exhibited here, unlike those in Alec’s show at the Weinstein Gallery last year, are presented in several different sizes. Exhibiting them like this sets up a hierarchy of scale that makes me wonder — since contemporary photography is currently in the midst of a big craze for the gigantic — if we’re being signaled by this to think the bigger photographs more important. It would be ironic if that were true, because for me one of the two or three strongest photographs in this show, “Danielle, Liverpool, United Kingdom,” is one of the smallest.

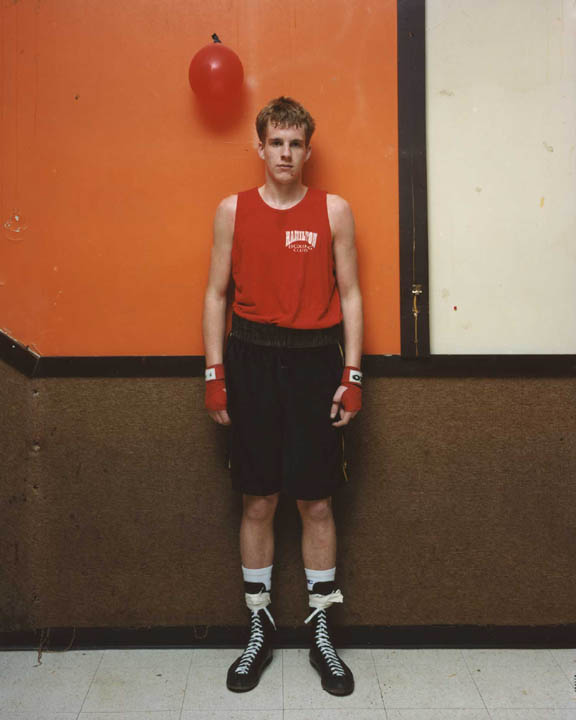

Someone pointed out to me that the exhibit’s opening shot, on the wall outside the gallery, “Daniel, Niagara Falls, Ontario” — the photo of the young boxer against the background of a kind of found Mondrian — is mounted on a spot nearly back to back with the provocative “Young Woman of Beijing” on the gallery wall just inside. As it happens, both of the figures are wearing shorts, and both have on tall black laced-up boots, so the parallels are clever and have some validity, but I think the real counterpoint to Daniel the Boxer is Danielle the Debutante. The composure of the subjects and the composition of both these portraits are dead-on. Daniel the boxer is linear — the roundest things in the picture are that sad little balloon and the neck of his singlet. Danielle, meanwhile, is heart-shaped: her face, her bodice, her slight plumpness. Her qualities reverberate through -– they could almost be said to inform — the pattern of the wallpaper behind her. Both pictures have stairs coming down at the same angle from the left. The two images are so serendipitously harmonic it would be fun to see them hung side by side. (Or we could make it a triangle, with the temptress from Beijing.)

There are eighteen portraits in this show. Looking at the representations of the women and then at those of the men, it emerges that Soth sees men and women almost as two entirely different species. The tenderness of his regard for women is apparent in Danielle’s composure and in wistful little Sydney from Tallahassee; and in his empathy for the frowning “Stacey, South Plains, Texas,” with those puzzled sheep looking at us through the fog; and in the slightly stiff pose and trace of uncertainty in the face of “Odessa, Joelton, Tennessee”; or in Soth’s capture of the way the “Young Woman of Beijing” tilts her pretty shoulder towards the camera.

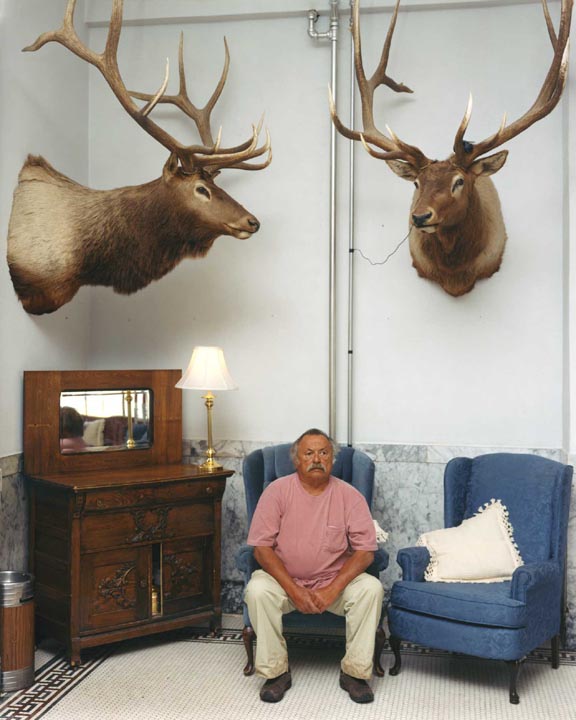

By contrast, most of the men in these portraits are regarded with a sort of comic melancholy. In one way or another, most of them are either doing something faintly absurd, like Josh with his military formation of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches or Boris feeding carrots through the juicer of his brain. Or, they’re captured amid the obsessions on which they stake their identities. The artist Andy Goldsworthy is portrayed earnestly maneuvering icicles; a couple of totally cool rockers stand in front of a totally cool meat locker; the novelist Jim Harrison, whom I believe has a wall eye, sits — his feet in exactly the same position as the armchairs’ –- juxtaposed under some plumbing with a couple of big elk heads on the wall, one of which has a security camera parked in its antlers, the eye of that camera as live as the stags’ glass eyes are dead; or, finally –- one of my favorites in the show –- the carefully composed portrait of Soth’s dealer, Martin Weinstein, standing there under the basketball hoop on the garage, an almost too perfect parody of a big shot with a cigar.

It’s hard to tell if Soth’s intent with these portraits of men is satirical or if it’s just the inevitable result of the fact that as men — especially when we’re men on a mission – we can’t help being ridiculous. Before I give you too much evidence in support of this conjecture myself, I’d like to turn this over to Michael Fallon who’ll now give you his own insights into Alec’s work.

The next article is Michael Fallon’s take on Alec Soth’s work from the same Trialogue occasion at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.