State Fair

World of Worlds

I’m sitting here after 16 hours at the State Fair, walking, seeing, eating, smelling. Especially the latter. It was hot out there. I’m trying to think about the 91st State Fair Art Show and finding it difficult to do so.

What do I have to show for all those hours? A heap of souvenirs and images, stuffed mermaids and fans-on-a-stick. Images of immense draft horses with feet the diameter of pizza pans, harnessed to small carts driven by sturdy men in fine woolens, driving in a line down Judson Street, turning in at the Hippodrome. A program from the horse-jumping competition. Lots of photos of cute bunnies, fancy pigeons, chickens. Some pictures of cows and sheep. A card from an artist in the “Wonders of Technology” building that speaks of art as “aesthetic research.” Photos of the lit-up Ferris wheel at night (the ride, invention of the American engineer George W. Gale Ferris, was a wonder of nineteenth-century tech). Images of rows and rows of pickles and beets in jars like jewels. And a stone sphere, some kind of fluorite, that I bought at a rock dealer’s stand, that is riven by striations on at least three different axes, visible only one at a time.

The sphere made me realize why the State Fair is written up so much. What’s the fascination? Well, like the stone ball that houses three different climates of light in the same small space, the Fair houses many superimposed volitional worlds.

Once upon a time, it seems, culture was dominated and formed by perceived historical necessity. There was a past and a future, and only one present moment to connect them. That moment had an internal consistency that meant that everyone grew up into the same world. You might want to do different things with that world, but in it 1930 was 1930, 1956 was 1956, and maybe 1970 was still 1970.

In this year of our various lords 2002, however, at least at the Fair and I think elsewhere too, it’s simultaneously 1890 (for the draft horse drivers), 1920 (on the midway), 1950 (in the buildings full of crafts), and so on. It’s a sort of concentration of the larger culture, which nowadays has decided on simultaneity. We live all historical moments at once, calling the ones we want to home. The loss of teleology is the gain of volition, of desire. The canners of vegetables and hookers of rugs can reside in a preindustrial aura; the booths in the “Wonders of Technology” building can invoke an unambiguous futurism that’s reminiscent of 1962 as much as it is of 2002. We inhabit the museum of history, which may or may not have a door leading to some self-consistent future.

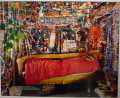

So in the Fine Arts Building it’s every decade of the twentieth century, and a few from various other points in the millennium. Every possible era of making is represented. Twenty years ago there was not the extreme diversity of style that one finds now: everything from beaux-arts landscape to seventies-style organic formalist ceramics to cute feminist underwear art to zine-like photocollage to formal abstraction to high midwest barn painting and animal art. The effect is somehow exhilarating and a little nauseating at the same time, sort of like a midway ride. The consistency of the world is upset, gravity is transgressed. Time travel, like spatial disorientation, can cause vertigo.

Is this the future of the artworld? It’s goofy to say that the State Fair Art Show is the rubric of the new avant garde, but the Fair makes an interesting case for a culture that is not heirarchically formed by ideas of necessity but grown from below, out of appetite, desire, and choice.

To see the work of some artists from the site who are involved in the State Fair Art Show, follow these links:

Leslie Anderson is the juror for paintings in watercolor, gouache, casein, and tempera.

Vince Leo is the juror for photography.

Kate Christopher is a past winner at the State Fair Art Show.

Photos by Erik Kalstrom