Starry Night

Andy Sturdevant revisits the long, strange career of Martin Woodrich with this story on the Minneapolis-based artist's surprising adventures in space.

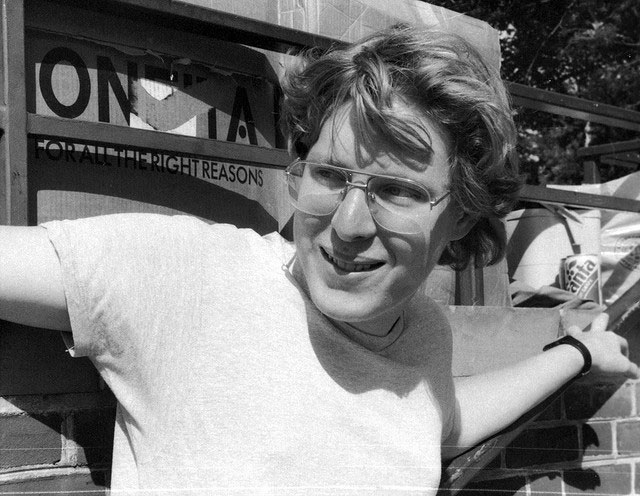

MARTIN WOODRICH ISN’T HAVING A GOOD YEAR. “I haven’t had a good year for a couple of years,” he says over coffee at a downtown Minneapolis Dunn Brothers. In 2011, the 61-year-old artist lost both his home and his job of over 30 years, as artist-in-residence for the Metropolitan Sports Facilities Commission. In the time since, he’s busied himself with making new artwork, trying to find a permanent place to live. He’s trying to make sense of the strange career that has taken him from Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) to the Metrodome and, now, to the furthest reaches of the solar system.

“Actually,” he says, staring down in his coffee, “they’re not not-good years so much as they are weird years.”

I notice his cellphone keeps buzzing. It’s on silent, so it just rattles its way across the top of the table every few minutes. It’s an old clamshell Nokia, given to him by a nephew. His old apartment, attached to his longtime studio at the Dome, had a landline with the same number for 30 years. He snaps the phone off the tabletop and tries to shut it off by mashing three of the keys together. “I don’t know why I have it on,” he says, frowning. “How are people even getting my number?”

I ask him who’s calling.

“Dorks. Mouthbreathers.” He frowns again at the phone and apologizes. “I’m sorry. That’s ungracious. They’re nice folks, mostly, but they’re a little obsessive. You know, science people, I guess. They’re all calling about Stevens. My painting — or, one of my paintings.” Apparently, there is suddenly a great deal of interest in a particular painting Woodrich completed more than 35 years ago. The original painting was a 2′ x 3′ abstract on canvas, Untitled (Stevens Square #3), created during his senior year at the MCAD. It is notable for two reasons: The first is that the painting was awarded a yellow ribbon at the 1975 Minnesota State Fair. The second is that it’s the only image of an oil painting made by an Earth artist to have traveled beyond the solar system into interstellar space.

It’s the latter distinction that keeps Martin’s cellphone buzzing.

***

In April of 1976, Martin Woodrich was 23 years old, a native of Judson Township, Minnesota (population 591) and a recent graduate of the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, where he earned a bachelor of fine arts in painting. That August, he boarded a Greyhound bus with a cardboard suitcase, a vinyl portfolio of small works, with a one-way ticket to New York City. “I had nothing going on in Minneapolis,” he says. “A trip to New York seemed like the natural thing for a young artist do. I didn’t know anything much about the city. All I knew is that was where artists lived.” He was looking to shop some of his paintings around in New York City, in hope of finding gallery representation.

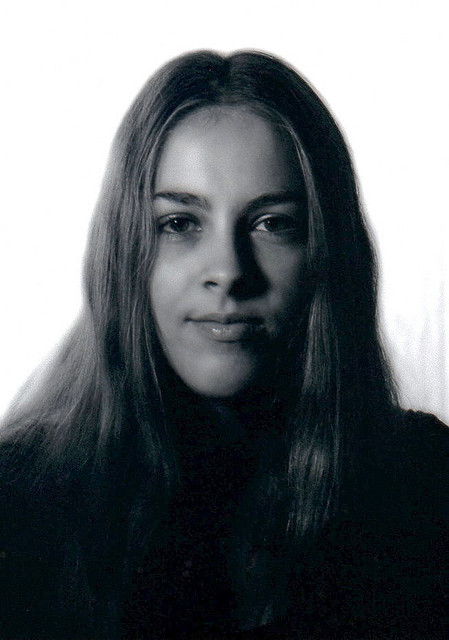

Martin didn’t make it to the city, though. He’d made plans to go, first, to Ithaca to stay with Sandra Jancourt, a friend and fellow MCAD alum. “I figured Ithaca was still in New York,” he explained. “I guess I thought I could just get a subway from Ithaca to Chelsea.” The two cities are, of course, nearly four hours apart by car. Martin didn’t make it down to New York City that summer.

Sandra was the only person in New York state Martin knew, and she’d invited him to Ithaca for a reason. Sandra was a few years older than Martin — she’d briefly dated his older brother — and had gotten her MFA from the College of Art, Architecture and Planning (AAP) at Cornell University, where she was teaching in 1976. She suggested there might be some opportunity for him to do the same; one of her colleagues in the painting department was taking a leave of absence for a semester, and she’d recommended Martin as a replacement. Martin made a good impression on the department faculty, and in Cornell’s AAP community, almost immediately upon arriving in town. A charming, good-natured and handsome young man who seemed older than his 23 years, he fit right into the academic lifestyle, making the rounds at dinner parties, university social functions, and art openings. He schmoozed effortlessly with the faculty. So, in September 1976, he began a temporary job at Cornell University teaching “Introduction to Drawing.”

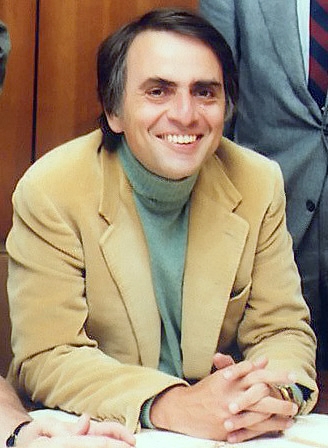

In October of the fall semester, Martin was sitting in a common area at Cornell’s Willard Straight Hall reading a copy of Charles Mackay’s 1841 catalog of scams and manias, Extraordinary Popular Delusions. “I’d been doing some stuff based on floral paintings,” Martin explained, “and there’s a great chapter in there about the Dutch tulip mania. I was trying to connect flowers and painting and commerce.” A thin, dark-haired professor wearing a turtleneck and corduroy jacket approached and told him Mackay’s books were also some of his favorites; he said he’d been including it on reading lists assigned to his students for years. The two men began discussing the book and hit it off immediately. The professor gave Martin his phone number and asked him to stop by his house that weekend to have dinner with him and his wife, also an artist.

The friendly stranger was Carl Sagan, director of Cornell’s Laboratory for Planetary Studies, and still a few years away from becoming the most well-known astronomer in the world. And so Martin Woodrich began a friendship with Sagan and his wife, the artist Linda Salzman. Once a week or so, he’d head over to their small house for dinner and conversation.

***

In late 1976 and early 1977, Sagan was engaged in putting together the continuation of a project he’d began with the Pioneer space probe in 1972. On that probe, he and Salzman had created a copper plaque that outlined a figure of a man and women, with some additional pictographic representations of Earth’s place in the solar system and the trajectory of the spacecraft, all for the benefit of intelligent extraterrestrial beings who might happen upon the craft in the centuries to follow. For the Voyager probe, which would travel even further into space, beyond our solar system, they’d expanded the idea significantly: in addition to a pictorial representation of a man and woman, Voyager would carry a golden record cataloging the sounds and sights of Earth at the end of the 20th century. In terms of its scope and its optimism, Voyager’s record is perhaps the most idealistic work of art in all of human history: thousands of years of humanity, summed up in a relatively tidy package, all in service to a cultural exchange that, if realized, would become the most important event in human history.

The cultural sampling on the record covers not just music, but also the sounds of nature: whales, the ocean, birds. It carries greetings in 55 languages, including Nepali (“Wishing you a peaceful future from the earthlings”) and Swedish (“Greetings from a computer programmer in the small university town of Ithaca on Planet Earth”). The music selections range from Stravinksy, Beethoven and Chuck Berry to performances from the court gamelan of Pura Paku Alaman, Senegalese percussionists, and a mariachi band from southern Mexico.

There are, however, no images of paintings or sculptures on Voyager’s golden record. Not exactly.

“We decided not to include artwork,” writes artist Jon Lomberg, who was charged with assembling visual images for the record. “Mostly because we didn’t feel competent to decide what art should be sent … We were so rushed in putting together the picture message that we couldn’t assemble experts in all the various visual arts and have them agree. And we thought extraterrestrials would have enough trouble interpreting photographs of reality or simple diagrams without our including a photo of a painting, which is itself an interpretation of reality.”

Instead, Lomberg and his colleagues assembled a selection of photographs from National Geographic magazines and a pile of reference books. These depict scientific images, but also photographs of, among many other things: an Amish barn-raising, the Great Wall of China, the United Nations building at day and at night, rush hour traffic in Thailand, and an astronaut in space. Several landscape photos by Ansel Adams are also included, more for their documentary than artistic value. (Though the extraterrestrials might be interested to find some significant differences between the landscapes as viewed in person and how they’re represented in the work of Adams, an enthusiastic retoucher).

“The criteria for the picture message was informative, not aesthetic, value,” concludes Lomberg.

***

In early 1977, Woodrich was back in Minneapolis, living and painting alone in the front room of a dilapidated mansion on Portland Avenue in South Minneapolis — the only room he could afford to heat in winter. His semester at Cornell had ended, and he’d returned West to make the most of the post-collegiate connections he still had in the Twin Cities. But Woodrich and Sagan kept in touch, writing letters and occasionally talking on the phone. (“He’d insist I call collect,” Woodrich recalls, “because I certainly didn’t have the money.”) Sagan also shared his work on Voyager’s golden record, which Woodrich found fascinating. “‘Carl,’ I’d say, ‘you’ve got to put a painting in there,” he remembers. “‘You’ve got to get a De Kooning in there, at least. If the aliens are going to know about what sort of stuff goes down on Earth, they’ve to know about paintings.’”

“At the time, I thought De Kooning was the best way to get that across,” he laughs. “I was a young man then. Now, of course, I’d say — oh, I don’t know, Agnes Martin. I’d send Agnes Martin into space. It sends a more…” He searches for the right word. “…a more optimistic message.”

“Martin,” Sagan told him one evening, in that famously distinctive voice. “You’re an authority on painting. You’ve taught at an Ivy League school. You have a good eye. We’re going to bring you in on this.”

Sagan informed Woodrich they needed a color photo of fire in action — ostensibly to showcase the Earth’s oxygen atmosphere — with some human models. And so, on a cold January night in 1977, Woodrich invited his friend Sandra Jancourt over to his house on Portland Avenue to take a photo. Jancourt was in town, visiting her parents over the break before classes at Cornell began again, and she was leaving for Ithaca shortly. She set up a tripod and Pentax camera in his home and took three shots of her and Woodrich. In the images, Woodrich sits on a stool, grinning and holding up the back of one of his paintings resting on the ground. The top half of his body is covered by the canvas. It’s about three feet high: a red, black, blue, brown, and white abstract painting, vaguely reminiscent of work by Richard Diebenkorn.

The painting in the photo is a piece he completed in 1975, formally called Untitled (Stevens Square #3). It was made in his studio in the brownstone Minneapolis neighborhood of the same name, while Woodrich was a senior at MCAD. It’s one of the pieces he brought with him to Cornell in that vinyl portfolio, hoping to win the notice of a New York gallery. In the photo, Martin sits next to a burning fire in the open hearth; Sandra is pictured sitting on the front bricks of the hearth. You can just make out a shutter release hidden in her left hand. Both are grinning wryly. Altogether the image looks a little bit like documentation of a performance art piece.

The requisite fire and the human subjects are there, but the painting is clearly the focal point. Jancourt brought the roll of film back to New York, where she had it developed. She passed the negative onto Sagan, who then passed it on to the committee.

And that is how Sandra Jancourt’s photograph House interior with artist and fire, depicting Martin Woodrich’s 1975 abstracted Minneapolis landscape, Untitled (Stevens Square #3), was included on the golden record sent aboard the Voyager spacecraft, now hurtling past the heliosphere into interstellar space. The only physical representation of a painting in human history to travel so far beyond the Earth is not by Da Vinci or Van Gogh or Hokusai or Caravaggio or Kahlo or Willem De Kooning or Agnes Martin — but by Martin Woodrich.

“We selected this picture primarily because it had a fireplace,” Lomberg wrote in 1977.

______________________________________________________

The only physical representation of a painting in human history to travel so far beyond the Earth is not by Da Vinci or Van Gogh or Hokusai or Caravaggio or Kahlo — but by Martin Woodrich.

______________________________________________________

All of this would just be an interesting footnote in local art history if that had been the end of it. But another 1970s-era space probe has since entered the picture and changed the meaning of Martin’s painting significantly. Last month, the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute, a nonprofit organization based in California dedicated to the discovery and exploration of life in the universe, made an announcement regarding the International Earth-Sun Explorer-4 (ICEE-4). The ICEE-4 is currently winding its way back to Earth after traveling around the sun since its launch in 1978, gathering data about solar wind and cosmic microwave background radiation. Though it was only created to operate and transmit data for a limited window of time, the ICEE-4 seems to be completely operational even now, decades later.

“NASA has said it no longer has the code to communicate with the spacecraft,” reads a SETI Institute press release. The engineers who programmed the original code are long retired, and though it’s passing close enough to Earth for the first time in two decades to communicate with, there doesn’t seem to be the interest at NASA in expending the time and money necessary to recreate the commands needed to access the probe’s data. So the ICEE-4 has been pinging at Earth, asking if we’re here, and waiting for a reply. Whatever it’s found around the sun in the past few decades is, at the moment, unknowable – the codes and commands necessary to request that information scrapped a decade ago. So, the ICEE-4 is incommunicado, waiting for requests in a language we no longer remember or have the capacity to understand.

Amateur radio operators, on the other hand, are a different matter. They have ingenuity and time aplenty to work to reproduce the code needed. And on March 15, a ham radio operator in Shakopee, Minnesota announced that the probe had passed close enough to Earth for him to detect a signal by way of a 10-foot helix antenna he’d rigged up in his backyard. He claims that, with the help of a few dozen colleagues across the world, he’d been able to work out commands to order the probe to release its data. The resulting information was readable on some custom radio equipment he’d connected to a 1970s-era oscilloscope he’d set up specifically for the purpose of interpreting the ICEE-4’s archaic transmissions.

The radio operator claims that the data he’s received from the ICEE-4 create a sort of pattern unlike anything typically associated with solar wind or background radiation. When shown on the oscilloscope, using time and bandwidth as axes, the duration of the pulses from the probe seemed to form shapes, like thick bars – too orderly to be simple background noise.

Of course, the online technical, scientific, and conspiracy communities exploded.

The original radio operator had put the information out there, asking if anyone could make sense of the results. Another Twin Cities-based amateur SETI enthusiast noted the unlikely similarity between the signal transcription from the ICEE-4 and the forms in Untitled (Stevens #3). Many others immediately agreed — there is some kind of link between Woodrich’s image and this data from the ICEE-4. Woodrich’s work may not be well-known in the larger art world, but in SETI circles, the Voyager golden record is one of the most famous artifacts around. Woodrich has a bit of a following among its enthusiasts.

Which raises numerous questions: what connection could there possibly be between decades-old readings of background radiation, itself millions of years old, and an encoded image embedded on another space probe that’s going in the exact opposite direction? Is this just a mistake on the part of the radio operator? Is it merely a passing resemblance of abstracted forms inflated in the imaginations of overeager amateurs? And even if the connection between them is rooted in truth: why Woodrich’s painting? Why not any of the other images on the golden record? Or what about the music that was included?

NASA has steadfastly refused comment on the matter. Some have suggested that NASA is fully aware of the connection, and their assertion that they were unable to access the data from ICEE-4 is an evasive maneuver, an excuse to not have to deal with this odd and potentially enormous issue right away. “Since when,” one tweet from an associate professor of astrophysics in New Jersey asks, “does NASA sleep on any tidbit of transmitted data?”

Look at the original painting side-by-side with a visual representation of the signals from ICEE-4, and there’s an undeniable similarity, as if someone were sending a description of the painting over Morse code, or painting a picture using signal strength and time in lieu of brush and oil paint. Woodrich’s abstracted, blocky vision of Stevens Square brownstones floating through red, thickly painted space translates surprisingly well into the format of a visualized radio communications on a screen or page. Carl Sagan, as noted earlier, had said as much himself.

Meanwhile, Martin’s phone continues to ring — amateur scientists, astronomers, tech reporters, anyone with an interest in extraterrestrial life wants to talk to him. The level of interest has, so far, been relatively focused to a small community. But that interest has been very intense and spreading outward – and it’s been happening quickly.

Just in the past few weeks, Martin has gotten calls detailing all sorts of schemes. One man in California called to discuss a Kickstarter campaign to raise money to send Woodrich to Washington, D.C. to petition NASA for an official statement in person. A newly formed 501c3 group in Nevada wants to recreate Stevens in the high desert, making it large enough to be visible from space. A petition is circulating online to make a simplified version of the painting the “accepted and universal symbol of the Earth and its culture, as a testament to this historic first communication between humankind and a higher intelligence we are just beginning to understand.” Woodrich’s art, it continues, “as a pure expression of human dignity, ingenuity and spirituality, unencumbered by the burden of slavish representation, is a universal language understood by all intelligent beings.” A wealthy collector and amateur UFOlogist in Taos, New Mexico has offered to buy as much of Woodrich’s work as the artist is willing to part with. Thus far, this has been coming from the more eccentric corners of the culture, and there are plenty of knowledgeable people out there that think this is all bad science. But even so, the idea that Woodrich’s painting might be a key to unlocking the secrets of human-extraterrestrial contact seems to be gaining momentum.

The funny thing is, Untitled (Stevens Square #3) is not actually that great a painting. This is a fact Woodrich himself happily admits. In fact, it’s not even as good as Untitled (Stevens Square #1) or Untitled (Stevens Square #2). The work a little sloppy and not particularly representative of his later paintings. In fact, it’s typical of his or any other painter’s earliest student work. Ironically, it’s just that blockiness, that crudeness of design, that makes it so well-suited for running through an oscilloscope.

“Of all the paintings I’ve ever made,” he says now, “it’s kind of embarrassing to think that’s the one that’ll be flying through space a million years from now.” He doesn’t even remember why he grabbed Stevens for the photo op — possibly because it had been with him to Ithaca and back, though he can’t remember if Sagan ever said anything about that painting, in particular. Sagan had seen a lot of his work; Woodrich had him over a few times. Sagan spoke about how, in particular, Woodrich’s love of intricate, messy patterns on his canvases reminded him of readouts of cosmic radiation.

“We talked a lot about science and art,” says Woodrich wistfully, gazing out the window of the coffee shop where we’re meeting.

Woodrich says he kept in touch on and off with Sagan until the scientist’s death in 1996; he traveled to Ithaca to attend the funeral. Sandra Jancourt remained at Cornell for another ten years, transferring next to the California College of the Arts and living in Oakland, where she became a fixture in the Bay Area art community. Jancourt died of lung cancer in 1998. Woodrich’s career, in the meantime, was not necessarily helped in any major way by his contribution to interstellar cultural exchange — he remembers, in an interview in 1982 for a residency program through the Metropolitan Sports Facilities Commission, “that they thought [the golden record material] was neat, but it wasn’t like, ‘oh, you’ve got your artwork in space, that’s cool, well, here’s a job.’ They were more like, ‘OK, you’re not a drunk and you showed up for the interview on time and no one else wants the job, here you go.’”

Another funny thing is that Martin doesn’t even own Stevens anymore. He hasn’t seen the painting for decades. He sold it to a wealthy collector in Minneapolis in 1981 — he’d prefer not to say who — where it’s remained part of a private collection for decades. And whoever the collector is, they’re not commenting on the recent buzz.

Woodrich is perplexed and somewhat bemused by the whole thing. He doesn’t know what to think. “I don’t want to say one way or the other. I think, if the aliens appreciate it, I have to think it just means they can’t paint,” he says, grinning. “Or, maybe that they can paint on the level of a college senior.”

“I guess if someone out there saw it and liked it enough to return the favor, I ought to be flattered. And I am flattered,” he says. “I just wish it had been a better painting.”

______________________________________________________

The actual photograph of Martin, Sandra Jancourt, and Untitled (Stevens Square #1) is still under copyright from Jancourt’s estate, and we couldn’t get permission to reproduce it here. To see the photo on her website and learn more about Martin Woodrich and some of the details mentioned in this piece, click here.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Andy Sturdevant is a writer and artist in Minneapolis. His most recent book, Potluck Supper with Meeting to Follow, was published by Coffee House Press in 2013.