Reality Show

Contemporary life blurs the boundaries between fact and fiction, reality and fantasy - we're accustomed, even numb to that fact. "More Real?" at the MIA takes a direct dive into this murky territory, where such questions and conundrums abound.

Situated at the end of a long, stately series of galleries, the entrance to More Real? Art in the Age of Truthiness is framed by white columns and a pediment — an ersatz classical facade that is itself ornamented with a triptych of LED screens. These bear the show’s title in animated graphics of the dazzling-yet-commonplace kind. This odd, ungainly appending of the digital to the classical signals that the world of More Real? is neither one nor the other. Rather, it’s the contrast and friction they generate, the questioning and disorientation, that are the essence of the exhibition.

In one sense, the 28 international artists represented in More Real? are simply carrying forward the venerable tradition of illusionism (in her catalogue essay, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts’ curator of contemporary art, Liz Armstrong, recounts Pliny the elder’s story about grapes painted so realistically they fooled birds). But they are doing so in head-spinning, often uncomfortable ways whose complexity matches that of contemporary life. Over the last few decades, technology and digital culture have given artists access to sophisticated tools exploring (and exploiting) realism that go far beyond paint, marble, film, and photography. Incorporating these tools, the works in More Real? are also characterized by layers and juxtapositions: new and old, digital and analog, classical and contemporary, factual and fanciful. Like the exhibition entrance, they show that it’s not a matter of the fake replacing the real, so much as the coexistence of both.

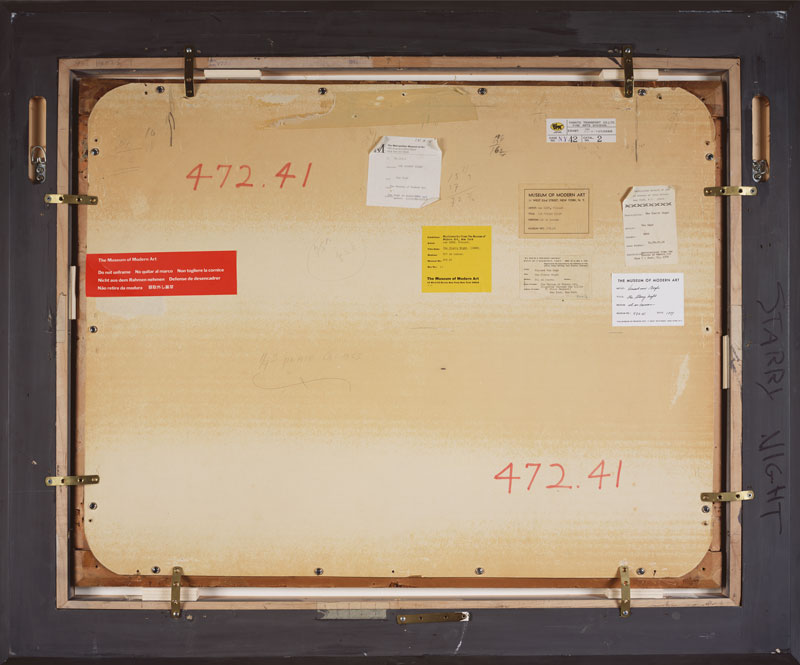

The exhibition is handily summarized through three noted themes – “Deception and Play: From Trompe l’oeil to the Authentic Fake;” “The Status of Fact: Unreliable Narrators, Parafiction, and Truthiness;” and “Reshaping the Real: Cinema, Memory, and the Virtual” – but once you’re inside, there are any number of ways to slice and dice the ideas on view. Indeed, that very open-endedness contributes to the hall-of-mirrors vibe throughout the show. For instance, another theme could be artists intervening in other artists’ works. Vik Muniz supposedly offers up masterpieces of Western art like Starry Night and American Gothic, but only their verso, or back side, is on display. So we’re left to marvel over how Muniz, known for creating astounding likenesses of people and landscapes with materials such as chocolate sauce or sugar, has mastered the art of forging the aged museum labels affixed to the backs of these works. Similarly, Ai Weiwei has appropriated a group of Chinese Neolithic pots and coated them with layers of lurid day-glow paint – but why trust the artist’s pronouncement about their age and authenticity, when he’s also run a studio of artisans turning out extremely convincing fake Neolithic pots?

Other interventions include Sharon Lockhart’s large-format photos of two museum workers installing Duane Hanson’s realistic human figures in a gallery, and a film by Eve Sussman | Rufus Corporation, 89 Seconds at Alcazar, which imagines the minutes leading up to the composition of Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor), Velázquez’s 1686 portrait of Spanish royalty and their court. In the case of Catt, a sculpture involving a real (albeit taxidermy) cat and bird, its creators, Eva and Franco Mattes, deliberately attributed the work to another artist, Maurizio Cattelan, building on a disturbing trend both in culture and politics: the ease with which something can be passed off as true or authentic, simply by proclaiming it so (or just wishing it were so, as with Stephen Colbert’s coinage “truthiness,” a touchstone for the entire exhibition). In that vein are Dreamland: The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and Its Circle, 1926-1972, Zoe Beloff’s extensive, fanciful historical display built around (it appears) only one true fact – Freud’s 1909 visit to Coney Island; and Walid Raad’s I only wish that I could weep, a video showing a series of sunsets from a Beirut boardwalk, banally beautiful views that supposedly distracted a supposed Lebanese secret agent from filming illicit activities.

That video is one of eight moving-image works included in the show, an unsurprising number given that film has been an essential means of blurring reality and fantasy practically since its invention. Certainly a show on this topic can’t ignore film and video, but the presence of these media in such numbers prompts questions: How many of these works does the average visitor watch in their entirety? Is doing so necessary or even intended by the artists? And when the number of film/video works reaches a critical mass in exhibitions such as this one, does that diminish their individual power to be affective, rather than just effective? That diminishment may not stem from any theoretical or conceptual flaw in the work itself, but is perhaps more a result of the degree to which screens permeate and mediate our everyday lives. In fact, that very phenomenon is demonstrated to disturbing effect with the Mattes’ video No Fun, which documents what happens when participants in Chatroulette, an online service whose users meet up randomly, encounter a supposed suicide on their computers.

By contrast, there’s Omer Fast’s Spielberg’s List – a 65-minute questioning of the ways history and memory mingle with storytelling, revealed during interviews with extras from Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List. Oddities and incongruities rise to the surface, but build slowly, as with any narrative film, and here are often near-impossible to ascertain.

______________________________________________________

Setting aside all logical flip-flops and double-takes and complicated back stories in the works on view, the show as a whole offers a cogent, convincing update to that dubious New Age tenet, “You create your own reality.”

______________________________________________________

More Real? expertly combines such works with others that have a blunt, more visceral power, such as Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s Phantom Truck, which is actually the dark heart of the show. His simple but sinister-looking fake, looming in a dark gallery, was inspired by a 2003 speech in which the U.S.’s then-Secretary of State Colin Powell claimed Iraq was manufacturing chemical weapons in special labs inside trucks, and showed computer-generated images of the supposed trucks. The invasion of Iraq, which just marked its tenth anniversary, took place a year later.

Spielberg’s List and Phantom Truck are just two of many works in More Real? that deal with war and/or politics. While not an official theme, taken together, these works not only give the show a gravity and timeliness but also serve as a reminder that the evanescence of politics leads to very real consequences of war.

Which brings us back to the first works viewers encounter in More Real?: Photographs from Thomas Demand’s Presidency I-V series, situated just behind that fake Greco-Roman entrance. The images seem authoritative at first glance, even if you know they represent a life-sized imitation of the Oval Office constructed entirely of paper. But once you notice the absence of key details like stars on the flag or faces for the figures in the picture frames, these simulacra serve as a metaphor for the ways in which image and surface trump in-depth reality in so many contemporary contexts: Why offer a complete picture when a sketch will suffice — and when often it’s all that’s desired anyway?

Writing on these works, Armstrong says Demand shows how “reality is not something that exists but is something that we construct.” In fact, setting aside all the flip-flops of logic and double-takes and complicated back stories in the works the curator has brought together, the show as a whole offers a cogent, convincing update to that dubious New Age tenet, “You create your own reality.”

For many of us, though, lived reality is already characterized by the notion of “blurred boundaries” — between fact and fiction, truth and simulation, reality and fantasy. We’ve become accustomed and even numb to breezy acknowledgements of this state of being. The punch of More Real? comes from its direct dive into this murky, edge-less territory, where questions and conundrums abound, but answers and absolutes are absent.

______________________________________________________

Related exhibition details:

More Real? Art in the Age of Truthiness will be on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts through June 9, 2013. For more information on related events and programs: http://www.artsmia.org/more-real/events.php#events

______________________________________________________

About the author: Julie Caniglia is a freelance writer and editor living in Minneapolis.