Profile of a Printmaker: Cecilia Lieder

Julia Durst describes the life and work of Cecilia Lieder, a printmaker and gallerist in Duluth, one of the founders of the Northern Print Alliance, which opens a new show October 14.

Across from the bustle of Whole Foods Co-op on 14th Avenue East in Duluth sits a world many walk by but few have explored. Inside a rambling, century-old green-and-white home snuggled into the steep hillside is a trove of art prints. Printmaker Cecilia Lieder has transformed the first floor of her house into a gallery that exhibits only prints by regional artists. A daunting task for most, opening the gallery was just the next natural step for Lieder, whose career in art has spanned decades and weathered many trials and travels.

All Roads Lead to Duluth…

Her fierce loyalty to Duluth leads one to believe she’s a born-and-bred Hillsider, but Cecilia Lieder actually hails from Minneapolis. She received her B.A. in fine art and English from the College of St. Catherine in St. Paul in 1964. She settled in Duluth with her then-husband Steve in 1970, where she earned her M.A. in fine art (sculpture and printmaking emphasis) from UMD.

Both she and her former husband worked as professional artists in Duluth–he as a potter, she as a printmaker. The couple had three sons and made their living at art fairs. Following a car accident her husband was involved in, and prompted by their 16-year-old son’s desire to further his ballet career on the East Coast, the family moved to Boston in 1983. Steve would learn to make violins and Cecilia would continue doing art. She got a chilly reception by the Boston art community, though, and recalls how hard it was to find venues to show her work.

“When I’d walk into a gallery and ask about having a show, I was actually told, ‘You have to be dead to show in this gallery.’” Lieder laughs, shaking her head in disbelief. “The community just didn’t really support its artists.” The decade spent in Massachusetts wasn’t a total wash—Lieder exhibited in a handful of shows in the state from 1986 to 1992.

Duluth’s art community underwent a massive transformation in the time Lieder was gone. When she moved back in 1993, she was stunned by the progress the Tweed Museum of Art, the UMD art department, and the Duluth Art Institute had made. Galleries were thriving; artists were staying. Looking back to the thirteen years she spent in Duluth in the 1970s and early 1980s, Lieder remarks, “It was a hard time for artists in Duluth… We were poor, but we made a living on art. That was amazing, but we didn’t realize it at the time.” The artist population lacked community support then, she insists. “Artists were leaving Duluth like rats off a sinking ship.”

Thrilled by what she found upon returning, Cecilia Lieder has called Duluth home for the past eleven years, assuming an active role in the local art scene by joining existing organizations and starting some of her own. She’s an organizer by nature, a rare specimen who has grand ideas and then systematically executes them. Her resume is a mile long, and she shows no sign of slowing down. It’s easy to forget what is buried beneath the titles and degrees. When the accolades fall away, there is an artist.

A Printmaker’s Printmaker

Artists, if you think about it, are a sort of an anomaly. They are laborers, attacking canvases, massaging clay, nicking at birch plywood in the pursuit of something more important than just the product of their toils. But they are thinkers too, ideamongers with six-minute soliloquies explaining the selection of a specific hue. They contradict the notion that society divides itself into the thinkers and the makers. Architects design bridges, but they don’t dirty their hands building them. Artists, on the other hand, often relish the calluses.

Cecilia Lieder epitomizes the thinker and the maker. Her years as a student, teacher, and artist have yielded great technical proficiency, which matches the intellectual, almost existential, way she discusses her work. She is experienced in both printmaking and sculpture.

Lieder works in relief printmaking most frequently, describing her prints as “painterly woodcuts.” She uses birch plywood for her blocks and usually works with eight colors (the minimum she says she needs to achieve realism), sometimes using up to sixteen. She prints editions of 50 to 75, and hand-rubs all of her prints. The process is labor intensive, but it allows her to control the color density and texture of the ink.

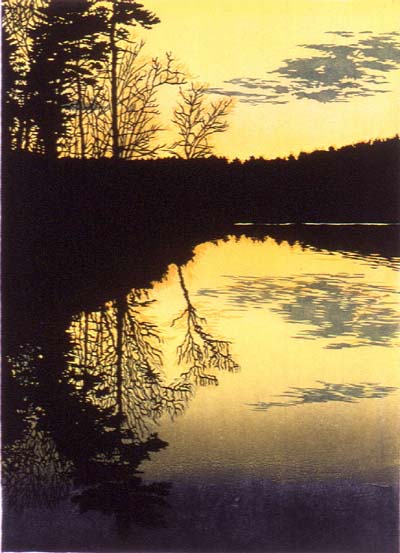

The effect is amazing. Perhaps best known for her renditions of the natural world, Lieder’s prints are detailed and engaging. Her ability to translate the changing light of dusk and the nervousness of water defies the characteristic hard-edge appearance of relief prints. “Immanence,” a seven-color woodcut, reveals Lieder’s sensitivity to color and form. Veiny tree limbs creep past the horizon into a honey-colored sky. A smattering of clouds punctuates the glowing atmosphere as day ends, the darkened earth below already welcoming night. The medium neglects to assert itself—even educated eyes forget that this is a print, the work of inexhaustible hands. (The edition of 75 has seven colors, meaning likely over 500 rubs of the blocks.) You know this place– you’ve seen this color sky and tasted this air. It becomes real.

“I call what I do ‘intentional realism,’” says Lieder. “I work from things outside of me. I didn’t always– it became a discipline for me. You have to really look at things… I search for the meaning of things, not their purpose… what they really are. In that constant battle between what I think and what is, that tussle, eventually I give in and grow.”

Formerly curious about surrealism and abstraction, the artist finds her brand of realism the most challenging and satisfying. “I’m not resisting anything anymore,” she says. “At age 52, something happened, something changed… and I made 50 prints in a short amount of time.” She came to realize that “the artist’s responsibility is truth—not just the happy and the pretty.”

Artist as Curator

In 1998, a small group of local artists “wanted to do something with the Hillside,” recalls Lieder, referring to the downtown area and just beyond, a part of the city known for its socioeconomic and racial diversity and its troubles with homelessness and crime. “We wanted to re-image the Hillside. In Boston they called it gentrification.”

She joined with Robb Quisling and John Steffl in organizing “Perspectives on the Hillside.” The project included musical performances and a three-week exhibit of artwork by over 30 men, women, and children from Duluth’s Central Hillside neighborhood. The Washington Center (a studio/gallery co-op) and Sacred Heart Music Center hosted the show.

The project’s impact on the community and on Lieder herself proved greater than she anticipated. “It was like I found my roots in Duluth again, meeting everyone… It was the first major visual arts event at Sacred Heart… and there were over 1,000 walk-in visitors. The whole community welcomed it, not just the art community.” She cites its importance as twofold: “First, it was a forum for the value of art. It got people talking, brought attention to the art community. Secondly, it gave a disenfranchised population an identity. The people of the Hillside were given a voice.”

Since returning to Duluth in 1993, Lieder has been involved with the Duluth Public Arts Commission, the Tweed Museum of Art, and the Duluth Art Institute. She has taught at UMD and done several workshops, and is currently the director of the Talley Gallery at Bemidji State University in Bemidji, Minn. In 1999, she founded the Northern Prints Alliance, and in 2003, opened Northern Prints Gallery to exhibit its members’ work.

Northern Prints Alliance resulted, as Lieder tells it, from a dare put forth by Joel Cooper, another local printmaker. Lieder had marveled that no such organization already existed and, as is her style, became pro-active to remedy the situation. The NPA strives to “promote traditional printmaking techniques through exhibitions and educational opportunities for the public and its members.” The group started with six members and grew to 20 by the end of 1999. Members include several familiar and well-established area artists: Betsy Bowen, Larry Basky, Jeffrey Kalstrom, and Earl Austin. Lieder intends to keep the group small and plans to cap the membership count, currently 28, at 50. Any regional printmaker can apply to join.

The group exhibits regularly at Northern Prints Gallery, yet another of Cecilia Lieder’s undertakings. In late 2003, the artist was faced with a vacancy in the lower duplex of the east Hillside house she owns. “I thought, I can rent it out or I can do something for printmakers in it.” She felt a gallery catering exclusively to prints would be a worthwhile effort. “I think it’s an unfair competition, to put prints next to other two-dimensional work. Prints are kind of on the dividing line between craft and art. In galleries, they never sell as well as paintings do.”

The gallery features only prints, but the variety is astonishing. The exhibited work, all by the members of the NPA, varies in scale and color, technique and style. Etching, lithography, screenprinting, woodcuts, wood engravings and linocuts fill the walls of Lieder’s home. With its lush red rug, majestic fireplace, small upright piano and comfortable chairs, the gallery’s environment is comfortable. The domestic setting makes the art more approachable and allows potential buyers to better see how the artwork might look in their own home.

Northern Prints Gallery has hosted eight shows thus far in its inaugural year. For each show, Lieder puts out a call for work to the NPA and they submit prints to fit the show’s theme. Past themes include black-and-white prints, the alphabet, and, most recently, northern landscapes.

“Shared Visions,” the gallery’s ninth exhibit, opens on October 14. The NPA paired with the Lake Superior Writers for the collaborative show. The writers authored poems, and printmakers then selected ones for which they would make corresponding prints. The 24 previously unpublished poems will be on display alongside the printmakers’ interpretations of them. Lieder was very enthusiastic about the two organizations teaming up and says they’ll do it again—only next time, the printmakers will do their pieces first, and the writers will have to tackle the task of translating it into their medium.

Her boys are now scattered across the country—one son in California, one in Milwaukee, one nearby in Duluth. She’s also no longer married. The business of art consumes as much of her as the art of art, with her own gallery to run and her work at the Talley. But Cecilia Lieder has come to where she is, a green-and-white house that breathes the lake wind, in a round-about-detour-through-Boston sort of way. It doesn’t bother her. Life is a lot like printmaking— a process. Some people send it through the press; Lieder does it by hand.

Considering the concept of process and how it implicates value, she recalls a quote by Henry David Thoreau, paraphrasing, “The cost of thing is how long it takes.”

Her experiences, then, are priceless, and the knowledge and perspective they bring, golden.