Poetry in Motion

Writer Alison Morse checks out a collaboration spearheaded by acclaimed poet Todd Boss and animator Angella Kassube, "Motionpoems," which aims to use moving images to "embed poems in people's consciousness," and to create a larger audience for both forms.

Every time I walked into an elevator at the 2009 Associated Writing Programs conference — an annual gathering of thousands of writers, poets, and writing teachers from all over the country — I heard the strangest muzak: a tinkly synthesizer riff, crowd murmurs, then a disembodied voice reading a poem. At the same time, on a tiny video screen above the elevator buttons, the words of the poem scrolled, danced, or popped on and off, accompanied by crudely drawn animated images.

This elevator entertainment, funded by The Poetry Foundation and created by students at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, is part of a project called Poetry Everywhere; it is designed to bring “a broad spectrum of poetic voices,” by some of America’s most respected living poets, to people unaccustomed to reading poems, in order to “build an appreciation and an audience for poetry.” Anyone can view the 34 videos on the Poetry Everywhere website, on YouTube, after Masterpiece Theater, and in the occasional elevator.

Some people might balk at the pairing of a medium used to sell Coca-Cola with what is arguably the pinnacle of literary art, but, as a former animator and sometime writer of poetry, I love the idea. Animation and poetry have a lot more in common than you might think: both are time-based, play with rhythm and repetition, and rely heavily on strong images and non-linear logic.

The Poetry Foundation is not alone in its ambition to turn erudite poetry into short cartoons. Twin-Cities animator Angella Kassube and St. Paul poet Todd Boss teamed up in 2008 to make their own version of animated poetry, which they call Motionpoems. The spark for Motionpoems was ignited when Angella, an art director at video post-production house HDMG and an avid reader of poetry journals, found one of Todd’s poems in Poetry magazine. Inspired by his musical, accessible poetry and Midwestern farm boy roots, which mirrored her own background, Angella began to follow his work. She finally introduced herself at one of Todd’s readings. “I didn’t know what to say,” she remembers; so, she told Boss she was an animator. Boss, the director of external affairs at the Playwrights’ Center when he’s not writing poetry, knew nothing about animation at the time, but he sensed its promotional possibilities. He emailed Angella a poem, “Poverty and Paint,” from his debut collection, Yellowrocket:

don't mix. You can tell real hicks by the raw barn board. Red's a long- retired cliché; a modern farm is gray on gray.

He also sent her a simple idea for an animation: scroll the words of the poem over an image of a red barn that fades to gray.

“When he first told me, I thought it wasn’t going to work,” Angella confesses. But during her twenty-five minute commute to work “it started to form in my head. I picked a photo and font,” and two weeks later, with the addition of music and the voice of Todd himself reading the poem, “Poverty and Paint” became an animated short. “It’s still one of my favorites,” agree Boss and Kassube in a recent interview, and I can see why. The short’s spare imagery, minimal, but perfectly timed movement, with banjo melody underneath Todd’s clear, informal voiceover, together create a haunting interpretation of the poem.

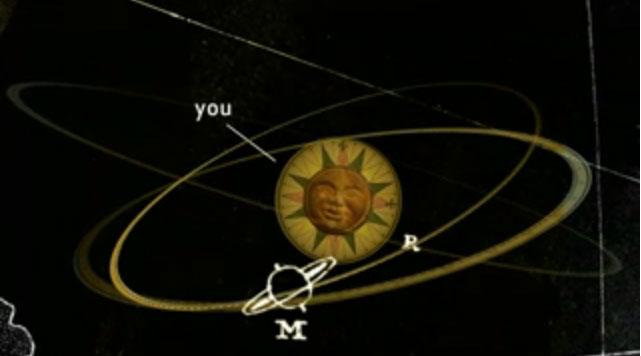

But Kassube wanted to show Boss what else animation could do for poetry, so she charted out a full storyboard for a second poem, “Constellations.” Todd had never seen a storyboard before. “I said, ‘Holy shit Angella .’ It looked so ambitious. But I thought, if she wants to do it, she should. By then, we’d built up a certain trust.” Soon Angella had turned three of Todd’s poems into short animated films and the new partners became even more ambitious.

“From the beginning,” says Angella , “I’ve wanted to bring poetry to people who don’t read, to friends of mine, people I work with.” She and Todd decided to expand their range to include several animators and multiple poems by revered national and local poets. They dubbed their initiative Motionpoems.

Motionpoems, Todd says, “is a great way to break the poetry distribution cycle,” where poems lie tucked away in poetry books or poetry journals that must be purchased in order to be read. “Individual poems become consumable for free in the hopes that people will read more,” said Boss; his aim sounds a lot like the mission statement for the Poetry Everywhere project.

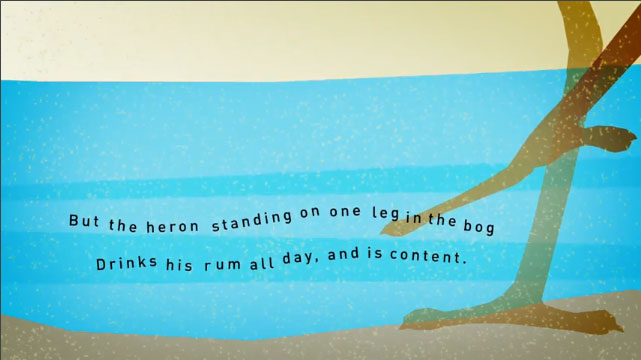

But unlike the animated poems commissioned by Poetry Everywhere — low-budget shorts by students — twelve of the thirteen completed Motionpoems are unpaid labors of love by professional animators (Angella supervised the only animation designed by an HDMG production intern), on state-of-the-art computer equipment. And it shows. These motion poems, as polished as any commercial work, employ lush color or equally evocative black and white, complex motion, and image-making techniques as diverse as layered video, multimedia collage, and 3D computer animation. The best of these animations do more than illustrate a poem; they “complexify” (to use Todd’s word) the reading experience. In Greg Mattern’s animation of Boss’s poem “How Smokes the Smolder,” Todd reads “no one races through the rooms alarmed,” while the camera pans across a group of marionettes with sculpted human heads on bodies made of household junk — it’s not a literal translation but an emotional interpretation of Boss’s words. When Kassube brings to life Thomas Lux’s coughs and “thank you” in her animation-in-progress of his poem, “Render, Render,” she adds another layer to my experience of the text: an awareness of the author himself and the uniqueness of this particular reading.

But can Motionpoems really create new audiences for poetry?

By the end of the first day of the AWP conference, I remember dreading the sensory assault of the Poetry Everywhere animations — and I was not the only one. Those elevators became battlegrounds for a war between passengers, who turned off the tiny TVs, and the conference staff, who turned them back on. Folks talked about how relieved they felt when they did not have to hear “those annoying animations.” Will the more professionally produced Motionpoems be seen as noise too?

The proof will come after distribution, a topic given relatively little attention by Kassube and Boss — at least for now. At the start of 2010, Motionpoems has a website, a channel on YouTube, and a deal with Twin Cities Public TV to begin airing Motionpoems on a new arts program, MN Original, in April; they’ve also landed a couple of film festival gigs. But, say Todd and Angella, “our concentration has been on creation.” They don’t yet have a plan to prevent Motionpoems from becoming as annoyingly ubiquitous as a TV commercial.

Still, if anyone can bring new audiences to poetry through animation, these two can. Both are smart, passionate promoters (and former 4-Hers), open to any and all possibilities for their project. They talk about bringing Motionpoems to schools, creating a feature-length film, and turning the animations into iPhone apps. Motionpoems does not yet have a range of culturally diverse poetic voices on their website, but there are at least twenty new animated poems in the works. As a fan of animated poetry and all its possibilities, I hope Kassube and Boss’s Motionpoems succeed in their ambitious plan, as Angella says, “to embed poems in people’s consciousness” and create a larger audience for both art forms.

Related event: The “motionpoem” below, “The God of Our Farm Had Blades” created by Pixelfarm’s Tom Jacobsen, Jesse Marks and Ken Chastain around a poem by Todd Boss, will be screened in this year’s Minneapolis/St. Paul International Film Festival, April 22, at St. Anthony Main.

About the author: Alison Morse’s poetry and prose have been published in Natural Bridge, Water~Stone, Rhino, Opium Magazine, The Potomac, and a bunch of other journals. Her short short story, “The Apartment,” was a 2009 mnartists.org miniStories competition winner. She is currently spit-polishing a novel, The Beethoven Frieze, about animators during Yugoslavia’s collapse. For twenty years she animated everything from cigarettes and glass shards to Barbie doing aerobics on the beach in Cancun. Now she teaches at North Hennepin Community College and runs TalkingImageConnection, an organization that brings together writers, contemporary visual artists and new audiences. The next TIC reading, “Back to the Garden,” will be on March 27, 8pm at the Soap Factory.