Identity, Art, and Responsibility: An Artist’s Journey in Diaspora

A conversation with artist Ziba Rajabi: on painting as a representation of the body in space, the complexities of translation, and how her immigration experience has changed her practice

A conversation was held between two friends, both of whom exist within the art world while occupying what feels like an interdisciplinary liminal space. One an immigrant and the other a non-immigrant temporary visa holder, they spent an evening discussing how these circumstances inevitably affect the creative process, and, more importantly, the emotional nature of human existence. What follows is an attempt at capturing the main points of their discussion.

The dialogue began with reflections on identity. Ziba Rajabi expressed how her appearance often takes precedence over her artistic work, leading to professional discrimination. She believes that identity and the essence of an artist’s work should be considered together to move forward. Ziba recalled a challenging experience:

“I was a part of an exhibit which required us to put aside all political commentary and adhere to personal narratives regarding immigration. It is important to specify that I don’t have an immigrant status in this country while holding the O visa. During this exhibit, someone came up and asked me how long I have been separated from my family. I said it had been five years. They enthusiastically and almost optimistically dismissed the five years as nothing. My subject for that exhibit was the usage of 2D digital platforms for contact with family and loved ones for years, and how after some time, there is no concept of your family’s 3D occupation of space. This individual’s response had one message for me that day: ‘Your pain is not entertaining enough for me.’ It asked questions such as, ‘Why is it that you haven’t seen your parents for 20 years?’ ‘Why are they alive and well?’ ‘Why are you a successful artist exhibiting at a museum?’ ‘Why don’t you share the same fate as the less fortunate ones?’ ‘Why don’t you match my cliche of you?'”

Ziba pursued the O-1B visa1 to expand her professional experiences in the U.S. as an artist. She highlighted the financial and emotional challenges of obtaining and maintaining the visa, as well as the limited opportunities it offers. These limitations are not just due to its temporary nature, but also because many institutions choose not to work with an O visa holders, due to a lack of understanding regarding the visa’s requirements and worry regarding the complexities it may impose.

Ziba talked about her approach to her medium, painting, specifically as a result of her immigration experience. She emphasized the importance of breaking hierarchical norms in art and embracing various materials to express her fragmented identity.

“One of the last series I created when I was still in Iran was inspired by German Romanticism, specifically the work of Casper David Friedrich.2 They were all landscapes exploring the relationship of humans and external forces, may these forces be nature or concrete. The landscapes I created for that project were all imaginary, though inspired by Friedrich’s work. They acted as alternate realities for me, considering the lack of nature in Tehran where I had lived for 30 years. When I moved to Fayetteville, Arkansas, I was seeing the real depiction of those paintings with my own eyes every day. The light was noticeably different. It made the continuation of that type of work pointless to me, especially because I have never been a representational painter. I had to tend to the dual reality I was experiencing: the physical space I was now in, along with the psychological space I regularly occupied, which consisted of my memories, dreams, thoughts of home, etc. Both had an extremely strong presence. I had gotten used to a certain understanding in Iran regarding painting. Painting in Iran seems to have been established as a random selection of a period of history without much context. In the west, painting has historic continuity. It is attached to institutions, White men mostly engaged with it; it was predominantly done on stretched canvas, and it engaged with hierarchy of material. Oil and acrylic usage were, and continue to be, highly segregated, especially as determined by White men. In Iran, such hierarchies and separations exist, but they have a completely different nature. As I tried to work here in the U.S., I came to realize we simply don’t have a common language, and the way my White faculty members understand painting is considerably different from mine. Therefore, what I can do now is to disrupt the foundation of painting at large. I had to redefine it in a way that made sense to me. I began to think about the definition of painting: what principles are dictated and how can I break them? For example, I detached paintings from the wall and hung them on self-standing structures in the middle of the room. White painting continues to rely on attachment to the wall, while [Iranian] painting has lived in numerous different forms, such as the rugs we walk on every day. We have walked on those stories for years.

I realized that painting, for me, has also been a representation of my body in space. As political relationships between Iran and the U.S. got more and more complicated, I found myself on the floor of my studio, cutting my unstretched canvas apart. I began this process of cutting and restitching as a representation of my own fragmented identity that was now in constant flux. One of my pieces, Misordered Story, references the idea of size and scale as a political stance, because it is simply so large and occupies so much space that one can’t walk in a room and ignore it; it imposes itself upon the viewer.

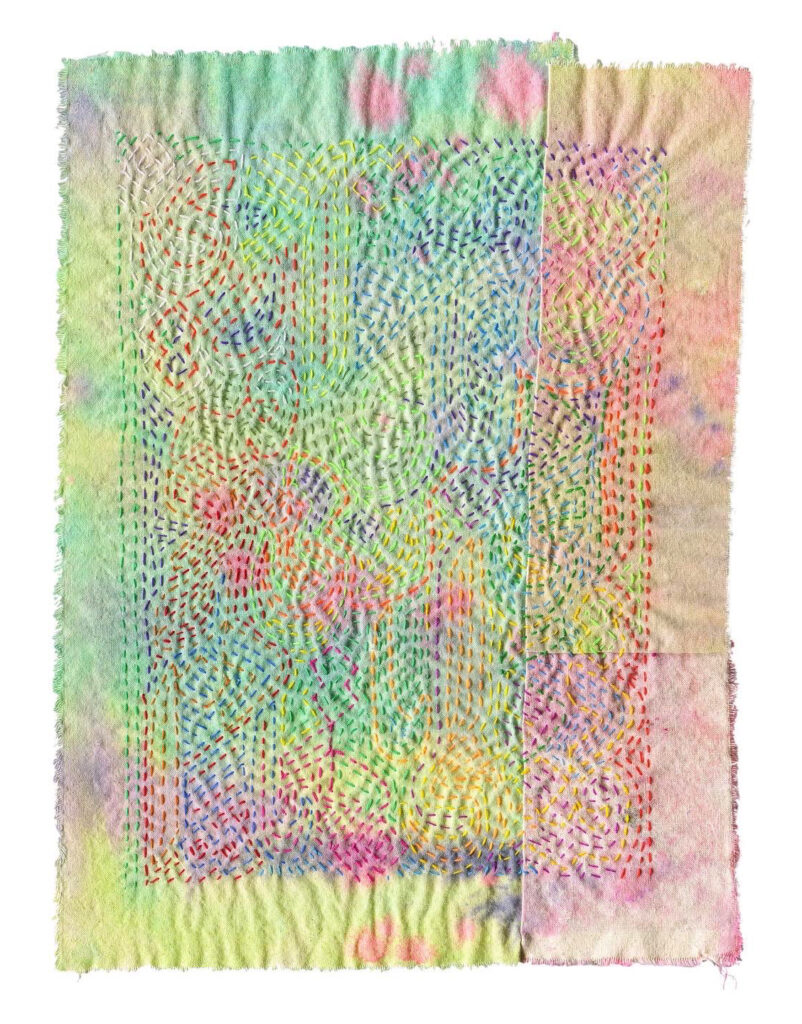

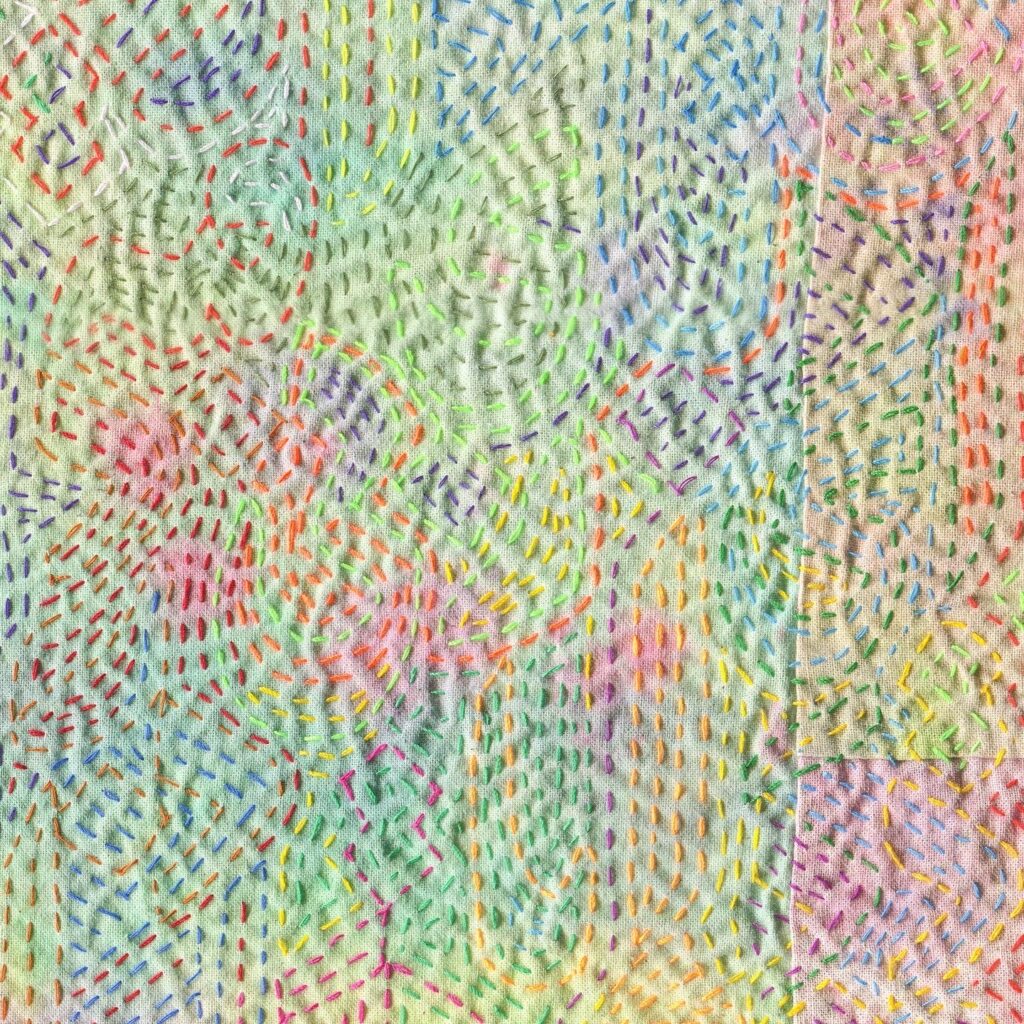

I had a studio visit with artist and long time activist Carrie Moyer.3 She advised me to read High Times Hard Times4 and to find my voice amongst others who have either struggled similarly or had asked similar questions. This quest has allowed me to work further and further with different materials. I currently work on muslin and have come to wonder: if we are questioning everything, then why not question mark making? Is mark making solely done via paint, pen, pencil? If I’m thinking of my female identity and my ancestors, did they not sew and knit to create? My current work is a quest of understanding those so-called domestic practices and how they can be brought into high art and occupy a space that has never been granted to them.”

We delved into the topic of approachability in art and how some artists intentionally utilize their exotic identity to appeal to certain audiences. Ziba shared her thoughts on audience consideration, stating that she wants her art to challenge and inform viewers, even if it may not always be immediately approachable.

“I’m saying this because [in Iran] I rarely considered my audience, while now, I have to negotiate all the time. For example, if I’m using Farsi in my work, I can no longer rely on the audience being able to comprehend it. I have to add a translation. Also, does the image have something that the audience can comprehend without reading it? In other words, from an aesthetic standpoint, does the work communicate or not? On the other hand, I strongly believe that as an artist I should never minimize my audience or to lower my work standard simply because I want it to make sense. The audience must be informed by the artist to the best of their ability, and from that point on the audience must put in the effort to try and understand. If the audience refuses to try to get it, it isn’t my problem to solve. The audience can be guided. Didactics can be added. Other methods can be used to invite the audience into the work. This is what I believe: it’s okay if art is challenging. Art shouldn’t always be approachable.”

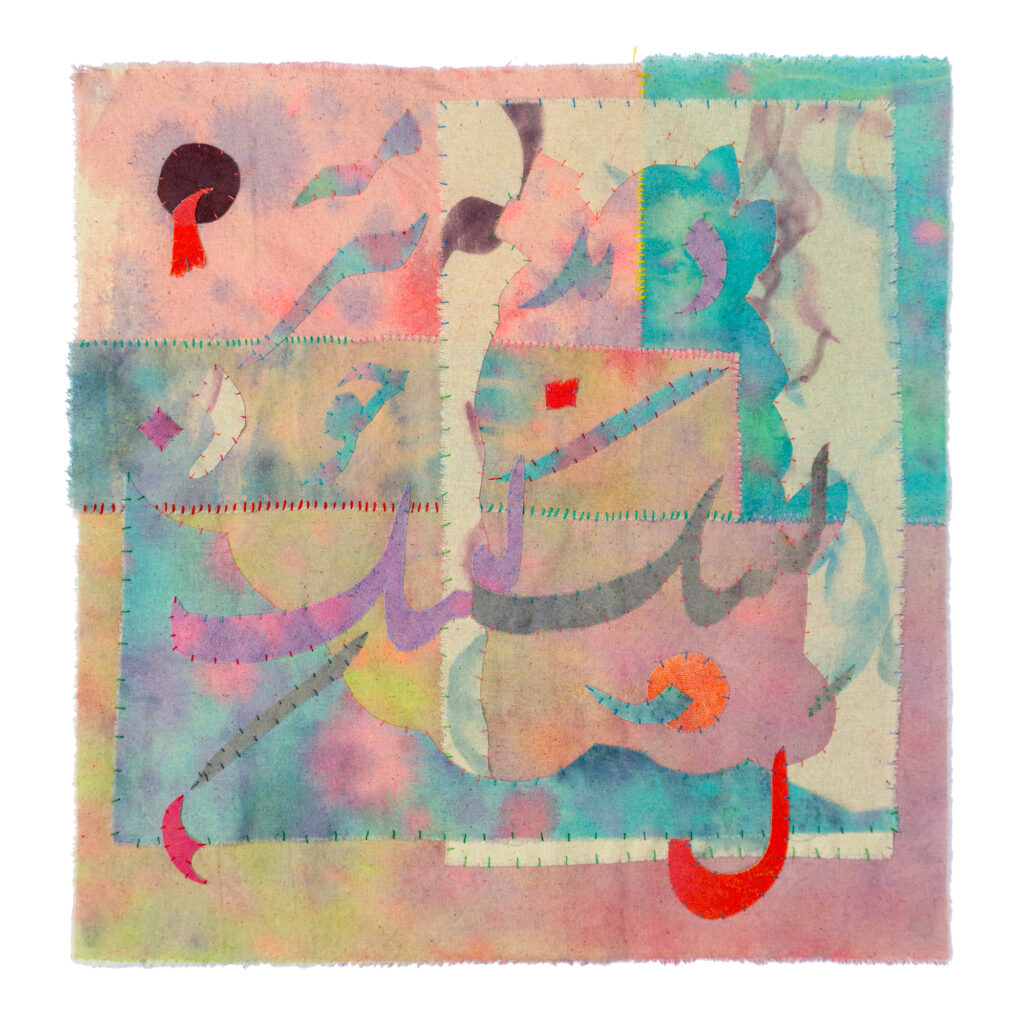

Ziba Rajabi, Deltang, 2023.

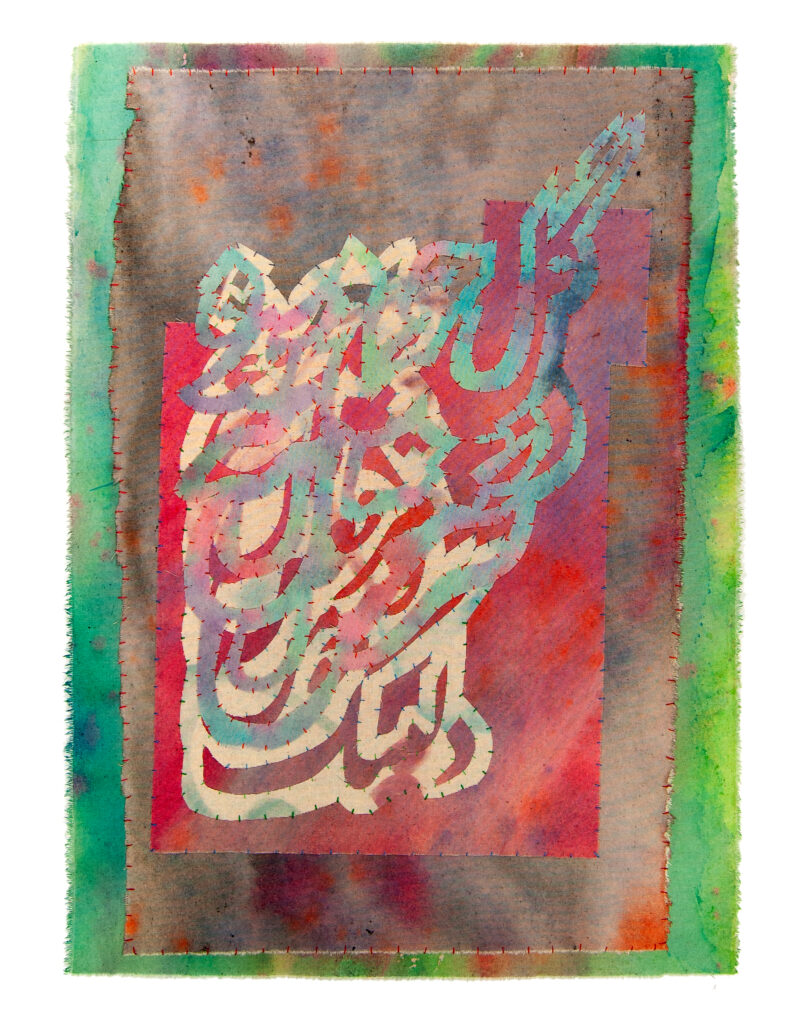

Ziba Rajabi, As a Bird Missing Her Land #1, 2023.

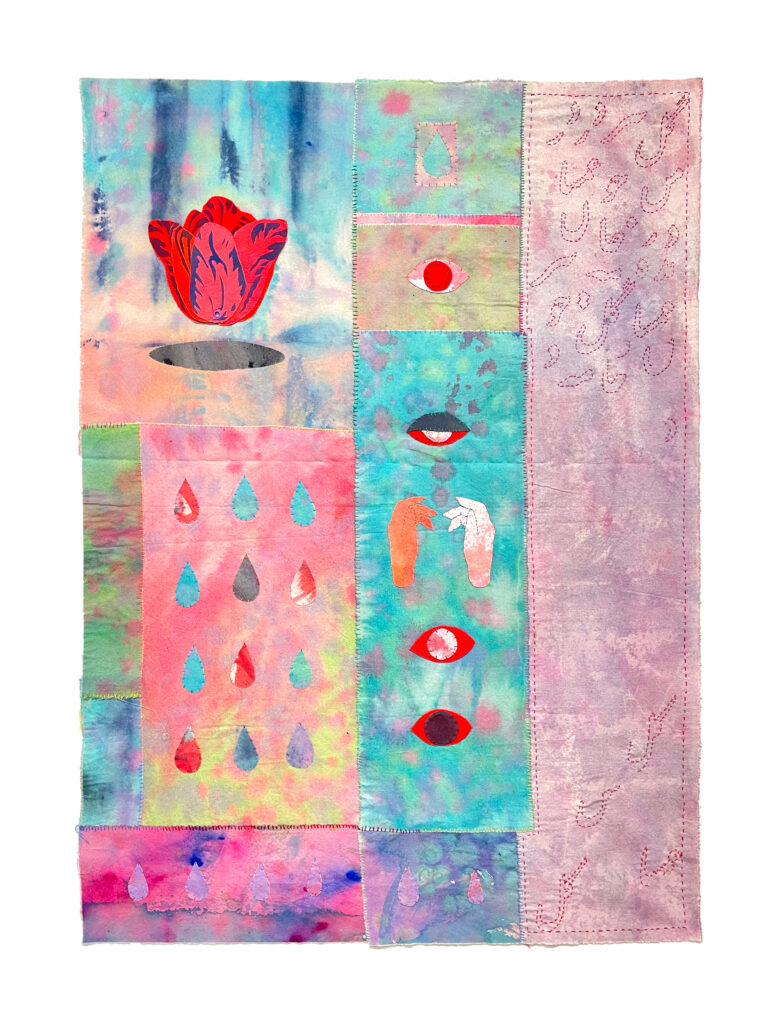

Ziba Rajabi, Only Tulips Grow on this Land, 2023.

Ziba Rajabi, Only Tulips Grow on this Land, 2023.

Ziba Rajabi, As a Bird Missing Her Land #2, 2023.

Complexity of utilizing translation in art was explored, especially when dealing with words and phrases that carry rich cultural meanings. Ziba discussed her struggle with representing the Farsi language and cultural nuances in her work for foreign audiences.

“Another example we were actually discussing last night was, ‘Ey yāreh rafteh.’ I asked my friend to tell me what it means to him. I found his response so interestingly unusual! Then I sent it to my partner and asked for his understanding. These were both vastly different from how I think of this phrase. For my partner, it represents a lover that has abandoned the beloved. For me, it represents us who have left our country and are being referenced from our family’s point of view. For my friend, it is a beloved who is currently traveling. This simple comparison shows the layers of translation. So we ultimately know that the meaning behind these words carries a history for each individual, and the history is not of a single-lined, linear nature and it’s thousands of years old. These words also change throughout history and find new meaning in the contexts within which they are defined and redefined. But when I have to choose a translation to supplement the didactic, I can only pick one. This again shows how communicating this experience becomes limited. But there is still a way. It is opening a door for the foreign audience member that most likely has no experience grappling with the layers of meaning embedded in ‘Ey yāreh rafteh.'”

As an Iranian female artist, Ziba reflected on how the recent uprisings in Iran influence her work. She considered the ethical responsibility of creating art related to these events without exploiting others’ suffering for personal gain.

“Despite the fact that this pain is extremely familiar to me and many of us, I have to tread very carefully as I create work regarding these recent events. I was in that exact room that Mahsa Amini was. What happened to her could have happened to any one of us. But I will never exhibit work that may bring me personal income that is generated from someone else’s suffering. My strategy from now on is to certainly keep the inevitable effects of the events in my work, however, I will never label or specify it with ‘woman, life, freedom.'”

The conversation concluded with discussions on the role of Iranians living in diaspora in creating change in Iran. Ziba emphasized the importance of listening to the requests of those inside Iran and being mindful of the cultural and political changes happening within the country.

“Wanting to do something is inevitable. We must continue to be allies while we also assess whether or not what we do is indeed helping. We have to accept that sometimes what we think as help can seem so from the outside, while actually causing harm on the inside. This has been the case with the most recent uprising. As hard as it may be, we must understand that we have to separate ourselves as those living in diaspora and listen to the requests of those inside Iran. We have to keep in mind that Iran is and has been changing at a high-speed rate. Being gone one year can mean total disconnect from cultural, social, and political understanding. It is fair to say that anyone who leaves carries with them a frozen snapshot of what Iran was like when they left it. Attempting to help from the outside without that deep inherent inside knowledge can mean helping with outdated means.”