On TASK

Andy Sturdevant reports back from the Twin Cities TASK party held in late April at Minneapolis College of Art and Design, the most recent of Brooklyn-based artist Oliver Herring's traveling community art-making parties.

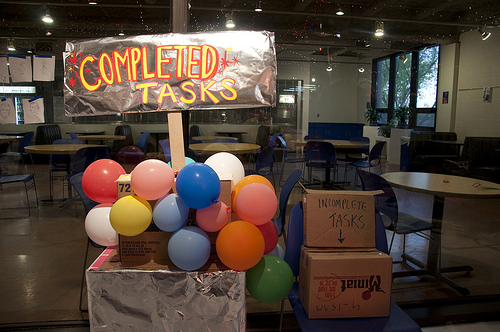

THIS IS HOW BROOKLYN-BASED ARTIST OLIVER HERRING’S TASK PARTIES WORK: first, everyone shows up at an appointed time and place. Many times the parties are held at a college, but they’ve also been at libraries, parks, and other public venues. Next, there is typically a box, and this box will be filled with slips of paper with open-ended tasks written on them by the participants. After the slips of paper are placed in the box, the participants draw them at random. The participant’s job, then, is to carry out the task in any way he or she interprets it. There are props all around the staging area for people to use, should they need to — paper, paint, glitter, tinfoil, etc. Once the task is completed to the participant’s satisfaction, it’s filed away in a second box, and the participant writes down a new task and submits it and draws a new one to carry out. And so it goes from there.

The Minneapolis College of Art and Design and Bethel University held a TASK party at MCAD on April 20, a day that held great significance for college students everywhere: a new episode of the cult television program Lost was airing, and it was 4/20, National Pot Smokers’ Day, the traditional day for celebrating marijuana use in its many forms. In a way, this was perfect — the vast majority of the TASK participants at the event were college students, so the evening already had a certain undergraduate woolliness to it. There’s a certain energy present in a room filled with college students, many of whom are likely thinking about smoke monsters or white widow. I showed up at 7:00 p.m., and stayed until 10:00, to observe Oliver Herring, who was present, as well as the college kids and everyone else participating, for the purposes of this account. To an equal extent, of course, I was also there to participate myself.

It’s impossible to write about a TASK party without inserting oneself right in the middle of the action. Everyone at a TASK party is an active participant in its creation and execution. To some extent, then, everyone is equally responsible for the success or failure of the venture. Though TASK parties are open-ended in such a way that there is not supposed to be “success” or “failure” in any objective sense, it’s completely reasonable to think certain behaviors would make for a more rewarding experience for everyone. A bad TASK party would be one where everyone showed up and argued with, contradicted, or actively ignored one another. The greatest TASK party would be the one in which all participants threw themselves into their projects with complete, uninhibited abandon. I imagine most TASK parties fall somewhere in the middle of this spectrum; actually, most human ventures fall somewhere in this middle of this spectrum. It’s in negotiating between these two poles that interesting socially-based art is made.

My first task struck me as fairly difficult. It seemed like it might be a kind of inside joke between two peers, but, even so, it worked well enough as a task anyone could carry out. The slip of paper read, “Find Jeremy So-and-So (guy with brown hair and glasses in a white ski resort t-shirt) and annoy him for 10 5 minutes.” Apparently, my unseen tasker decided at the last moment that asking for 10 minutes of annoying behavior was too much, a point I agreed with him or her on. Jeremy So-and-So, or at least a guy strongly fitting his description, was right in my line of sight, directly across the room. He was idly stacking boxes atop one another, stepping back to look at them every so often and scratching his head. Evidently, Jeremy was carrying out an inscrutable task of his own. His t-shirt had the name of a well-known ski resort on it. Obviously, he was my guy.

“Hey, guy!” I shouted in my best Louis Skolnik voice, as I walked up to Jeremy. “Hey,” he said back flatly, a response typical of college kids who’ve grown up on Adult Swim and 4chan and now find nothing bizarre. I continued: “What’re you working on? Isn’t this a crazy event? All these tasks!” I shuddered a little. I was already annoying myself.

Jeremy didn’t seem particularly annoyed, though. He was overly polite, if anything, so I pointed at his t-shirt and began telling him a loud, boring story about the ski resort that it advertised. As icky as I might have felt about it, my job was to annoy Jeremy for five minutes. If Jeremy wasn’t trying to get away from me, I wasn’t doing my job. I wondered if it might be more annoying to him if he were aware I was carrying out a task. I decided it would not be. It would be more annoying if he just thought I was a clingy jerk with loud, boring stories about ski resorts to share.

I must admit that few works of art have caused me to consider the metaphysics of annoyance in quite so immediate a way.

______________________________________________________

Getting art students to act out and wear tinfoil on their faces is no trick. Most would do so for no reason at all, which is why they’re in art school to begin with and not studying at the Carlson School of Management.

______________________________________________________

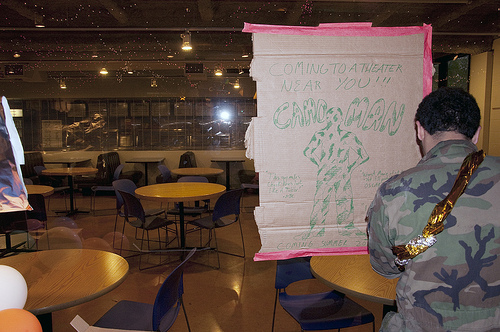

My inquiry came to an end two minutes in, when Oliver Herring himself walked up with a video camera for a quick Q&A. “What is your task?” he asked. I had no choice but to tip my hand. “I am supposed to annoy Jeremy for five minutes,” I said, showing him and Jeremy the slip of paper with the task written on it. “You are Jeremy, right?” I asked. “Yeah,” he said. I thanked him for taking the whole thing in stride. “I figured it was something like that,” he shrugged. I saw Jeremy wander by intently later on in the evening with a “KICK ME” sign taped to his back and tinfoil on his head. At the time, though, I was wearing an eye patch fashioned from pink masking tape.

Some of you reading might cringe at reading this — a roomful of art students milling around in pink eye patches and “KICK ME” signs. You might argue it sounds juvenile and silly and trite.

I admit I did wonder how TASK parties might vary from venue to venue. I have read quite stirring accounts of TASK parties that have occurred in public spaces with a full range of children, professional adults, and students. I hate to keep bringing up the college kids, who were uniformly a joy to interact with, but art school is an environment that rewards one-upmanship, histrionics, and grandstanding. Getting art students to act out and wear tinfoil on their faces is no trick. Most would do so for no reason at all, which is why they’re in art school to begin with and not studying at the Carlson School of Management.

An interpretation of TASK parties as an excuse to give self-absorbed youth another opportunity to yell, “Look at me!” misses a very important part of the equation, however. Half of the expectation for you, as a participant, is to assign tasks and, in doing so, to carefully consider what sort of tasks are worth assigning. It’s in these encounters that one begins to see the value in broad collaborative work of this nature.

The first task I submitted instructed the bearer to do the following: “Find another person roughly your age. Have a brief (3-5 minute) discussion about your personal memories and impressions of the Clinton presidency.” This year’s college freshmen were born in 1992, meaning they were eight years old at the end of Clinton’s term. Most of the TASK attendees at this event were college-aged kids, which means they are 22, at the oldest. I have such vivid and strong impressions of Bill Clinton, who was elected on the night of my 13th birthday, impeached my senior year of high school, and finished out his term my sophomore year of college. I wondered if people who had been children at the time had equally strong, though obviously quite different, impressions of his tenure. I began looking around the room, wondering which attendees were chatting about Bill Clinton, and what they might be saying about him.

Of course, even if this task was carried out — it may not have been — I have no way of knowing what kind of conversation the bearer of the task and his or her selected partner had. I can only trust that it was worthwhile for them in some way. Perhaps two people shared memories of watching the mid-term elections on TV with their parents in 1994 and considered how what they heard and saw molded their awareness of the larger world. Or, perhaps the person read the assignment, found it boring, and blew it off completely — there is no mechanism for enforcing task completion. That’s the thing about these events: you’re not only entrusting an unseen collaborator to carry out the task, you’re relying on them to do a good job with it as well. The party doesn’t work unless people are making a good faith effort to craft their requests, and an equally good faith effort to carry out those they receive.

To that end, one of my favorite interactions was based on a request that read, “Tell a boy a secret,” in a flowery, feminine hand. It may have been intended to give a female peer an opportunity for flirtation, but it was me — ungirly-ish me — that got the task. So I grabbed the shirtsleeve of a gangly freshman with braces who was walking by. “Hey, kid,” I told him. “This sheet says I have to tell you a secret.” He looked nervous. “Uh, OK.” So I told him the best secret I know of, which is to get your degree in four years and no more; you can always go back to school later if you want to, but you’ll be saddled with a ton of unnecessary debt later if you dawdle in your undergraduate years. He seemed relieved at the markedly non-salacious quality of my secret. We talked earnestly about college for a few minutes. It was a fairly good effort, I’d say, on both of our parts. More importantly, it was not a conversation I’d have had otherwise. After it was over, he went off to arrange a group of girls by their shirt color, and I went off to run three laps around the entire room at the request of yet another unseen collaborator.

______________________________________________________

Watch video from a TASK party from the University of North Carolina held March 20, 2010

Related exhibition:

Oliver Herring’s large-scale photographs, videos, performance work, and photo-sculpture are on view in a solo exhibition, TASK +, at Bethel University, in the Olson Gallery, through May 30. A second photo-sculpture by Herring is on view at MCAD.

Watch a video clip from an interview with Oliver Herring for Art21:

______________________________________________________

About the author: Andy Sturdevant is a writer, curator, and artist living in South Minneapolis.