On Criticism and the Glory of the New

Alex Starace peruses some recent art criticism, in particular articles on the Whitney Biennial. He discovers that, regardless of how good or bad the show was, reviewers could probably do better.

They say the art was ugly and childish; they say the curating was idiotic. They say the captions and wall texts were long, tedious, and didactic. I’ve read a lot of complaints about the Whitney Biennial, the paradigm new-art survey show. Writers say that the artists aren’t talented, the work is trite and infantile, gallery-goers don’t enjoy or understand what’s going on, and the curators are such pompous, conceited jerks that they can’t help but talk down to attendees in a fog of convoluted, empty jargon. (This article uses the Whitney show as an example, but similar complaints can often be found whenever a broad survey of new art is mounted.)

Laurie Fendrich in her article “Blowing Art-Theory Smoke” written for The Chronicle of Higher Education cites particularly egregious examples of bombastic and imprecise curatorial writing, dissects the problem with such writing, and makes suggestions for better, clearer statements (or, in many cases, no statements at all). And she’s convinced me with her judicious, witty, and methodical arguments. However, Fendrich seems to be an exception: most of the criticism I’ve read about the Biennial has come across as whiny and little more. Perhaps it’s because the show is so large that critics have difficulty taking the time to talk in detail about specific pieces–or perhaps the Whitney Biennial provides such an easy, juicy target that critics can’t help but take a lot of intellectual liberties when ripping into the thing.

The most common criticisms seem not directed at the show but at the direction the art world is heading: the schism between what people enjoy and what’s being created by artists is growing too large. As Lightsey Darst says in

“Whitney Again: What Does It Do?”: “When confronted with an installation consisting of many jars of pickled film, I feel irritated, I have to confess, annoyed at the dream of privilege in which someone thinks pickling film is a worthwhile contribution. Please, Mr. or Ms. Artist, go to the library, read a book, ask your neighbor for a story, examine the grass in your yard, do something, and then come back and talk to me.”

Darst assumes that her readers (and art viewers) can all agree that the activities she proposes are wholesome and life-affirming to the artistic mind. But is she correct? Are the behaviors she suggests truly salutary to artistic creation? Roughly speaking, she wants you to research the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at your local library, read a novel by John Updike, listen to your elderly neighbor spin a yarn full of colloquialisms and moral precepts, and then go outside and revel in the intricacy and glory of nature. This, she supposes, is what true and good artists do and think about. However, her suggestions, if followed casually, could also go this way: you go to the library and check out a DVD of Jaws, “read” Kenneth Goldsmith’s The Weather, shout at your jackass neighbor for playing his music too loud, and then go out to the parking lot of your apartment building and gaze at the pavement. Of course, despite your following her general outline in the latter case, this isn’t at all what she’d want you to do; Darst has a very clear sense of what’s important to her, how art should be arranged, and what art should do. The Whitney Biennial affirms none of her ideas about these things, and so, for these reasons, she doesn’t like the Biennial.

She’s entitled to this and, to her credit, she does a decent job describing a few of the problems with the show – in fact, she seems more even-handed than many critics. But I can’t shake the sensation that she’s relying a bit too much on glittering generalities and flippant remarks: I’d like to debunk the following idea: if only artists would once again make simple, beautiful, straightforward, and intelligent art like they did in the past, then the art world would get back on track and we’d no longer have to endure such sillinesses as the Whitney Biennial. It’s a lament that a chorus of onlookers is singing – philistines and art-lovers alike – and it’s a lament that strikes me as a bunch of hokum.

The Whitney Biennial is probably a good thing (no matter how bad it is), a fact that was recently affirmed for me while I was touring the galleries of the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts for the umpteenth time. Walking around, I was not getting the lift I used to get: as a high schooler, I considered the MIA the greatest building on the face of the earth. And even in college I was very fond of gazing at the paintings: it was there that I was first awed by the work of Chuck Close and Frank Stella. But now, in my mid-twenties and having been there many, many times, the general, “sampler” galleries are getting a bit stale – i.e., the work of Larry Rivers, though still fantastic, is no longer exciting. It is not new – I have seen, if not the exact piece hanging, many like it, and so seeing a particular one, scattered among other, similar pieces of a given era is, well, kind of boring.

And so what’s left? New stuff, of course. And that’s exactly what something like the Whitney Biennial gives us. Maybe, in the case of the Biennial, it’s bad new stuff – also boring, childish, repetitive, thoughtless, etc – but it is new nonetheless. And the fact that the evolution of art is continuing (however badly) is exciting: I’d rather go see the Whitney Biennial than stroll through the general exhibitions at the MIA for the nth time. This point seems to be lost among all those complaining about the Whitney Biennial: the art might be terrible, the curating unforgivable, and the combination of the two egregious, but (and this is passingly acknowledged in much of the criticism) a lot of the things tried are new. Unbearably long write-ups for each piece, an absurd amount of installations, infantilism and simplicity taken to dizzying heights: it’s all stuff that usually isn’t done – or at least that hasn’t yet been canonized. Someone, somewhere is trying – this I find refreshing and exciting. Perhaps the results aren’t great and maybe the effort is half-assed, but there it is: people are making new art, putting on a show, giving us something we’ve never seen before.

And yet most reviewers don’t seem to look at the Biennial as something to be engaged with on its own terms. As it seems to me, an excoriating review of the Biennial should first deign to take the show seriously, understand that it is intentionally unusual and reactionary, and then try to piece together reasons why it’s not successful. However, I’ve come across a distressing paucity of such reviews. Many writers are content to fuss that they personally didn’t like it, that it doesn’t display art that they are used to or fond of, cite an anecdote of some gallery-goers who were also confused/offended, discuss in sweeping terms the ills of the art world, and then reminisce about the days when art was art, men were men, and one could go to the gallery with a family and enjoy all the pretty pictures.

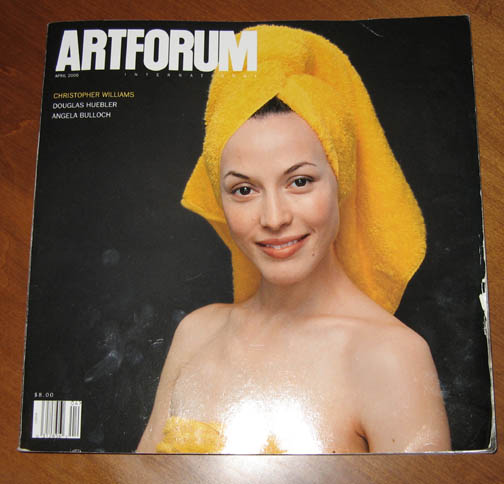

Maybe the Whitney Biennial has become another ArtForum, an endlessly pilloried entity in the art world, one that’s used as an emblem of various factions’ dissatisfaction. ArtForum is so consistently held up as an example of the folly of the academization of art that I decided to buy myself the current copy and read it – I was genuinely curious: Could this possibly be as opaque and conceited as everyone says? …Well, actually, no. The issue I read was filled with near-uniform excellence, intelligent and articulate. Sure, jargon was used and, sure, the articles required more concentration than a daily newspaper, but the results were worth it. The writers had ideas to express that couldn’t be expressed without complicated and intricate language. Furthermore, the writers wielded this language with precision and many of them showed a sense of humor. Moreover, the length of the main articles and the erudition of the reviewers (two commonly derided aspects of the magazine) served to give a depth to the ideas that simply isn’t available in shorter articles written by less informed people. Particularly memorable was the cover story, “What Does the Jellyfish Want?: The Art of Christopher Williams,” in which Bennett Simpson describes the visceral effect of attending a Williams show: “The decisive moment always lies elsewhere, buried deep inside the backstory of a chosen subject or ricocheting among groupings of images within an exhibition. This simultaneous deferral of and insistence on meaning lend a certain irony to the experience of Williams’s work.” Simpson’s article is complex, beautiful, and in its own way, a work of art. And quite a few of the other articles were as good as his: overall, I was deeply impressed with ArtForum and deeply disappointed that so many treat it with such glib scorn.

It seems the Whitney Biennial is falling into this category of misunderstood whipping boy. Maybe the show was bad – I didn’t see it; I live a long way from New York – but it seems reviewers should engage the art on its own terms, describe why it’s bad, what could be improved, and where it could go next. The Biennial presents us with an opportunity to wrestle with something contemporary and challenging, to use our intellectual skills, to think outside our comfort zone, to learn about new modes of expression, and to really write bang-up articles that explore new ground and that rigorously and effectively reject (or accept) what’s presented to us. It’s a chance to write a great review, and yet, as it is, it seems too many of us are simply forwarding our own preferences and preconceptions, whining and lamenting, and producing forgettable and trite screeds. This, to me, is a shame.