Night Haunts: What Creates the Body of the City?

Chris Atkins writes on "Night Haunts: A Nocturnal Journal Through 2006," a web project by Sukhdev Sandhu with visuals by Mind Unit and sound design by Scanner. It's one of Artangel's startlingly effective public art projects.

“With the vocabulary of objects and well-known words, they [urban narratives] create another dimension, in turn fantastical and delinquent, fearful and legitimating. For this reason, they render the city ‘believable,’ affect it with unknown depths to be inventoried, and open it up to journeys. They are the keys to the city; they give access to what it is: mythical”

–Michel de Certeau, “Ghosts in the City,” in The Practice of Everyday Life, Vol. 2

A living, breathing city is more than tangles of streets and alleys, traffic flows and jams, hidden histories and larger-than-life personalities. Some cities, as they grow and continue to grow, as people think them and write them, become more than collections of lives – they become characters in their own right. It’s as if the millions of words that have been written on the city streets have spilled into the gutters and now course like black blood through pipes and sewers, under streets and behind wallpaper.

Sukhdev Sandhu’s ongoing Night Haunts narrative is an online project. Every month he’ll release a dispatch from his forays that will then be posted on the Night Haunts website. Readers can subscribe to the website and be informed when each dispatch is available.

On the site, each story is accompanied by a visual collage and sound installation. Sandhu has tapped deep into the flows of London’s stories and streets with Night Haunts, documenting the nocturnal city that continues to move and flow while most of us sleep.

London’s city streets have been graffitoed and washed clean thousands of times, yet the city continues to absorb innumerable journeys and to inventory overlapping sojourns. London is a mythical city – and by this I don’t mean to imply that the city is in some way coeval with Atlantis and Babylon or that its history has somehow placed it beyond the realm of the real. London’s status as a city that has remained itself through millennia of change has created a mythology about it, with and through contemporary realities. That is, a multitude of stories have been written about London but it also contains stories that have yet to be written.

Having recently relocated to Minneapolis from London, I’m constantly trying to acquaint myself with this city. Instead of spending hours driving through the streets and pounding the sidewalks, I’ve found other means to look under the city’s surface and learn what lies beneath. Many of the Minneapolis and Minnesota blogs and vlogs like MN Stories and Perfect Duluth Day use journalistic or documentary formats that provide news and insight into unique personalities and sub-cultures: they don’t, though, ask any questions about the city itself and its diverse communities, languages, and ethnic realities. In seeking to look further into Minneapolis, or any city, how might an online project like Night Haunts help us reconfigure our ideas of our own urban histories and spaces?

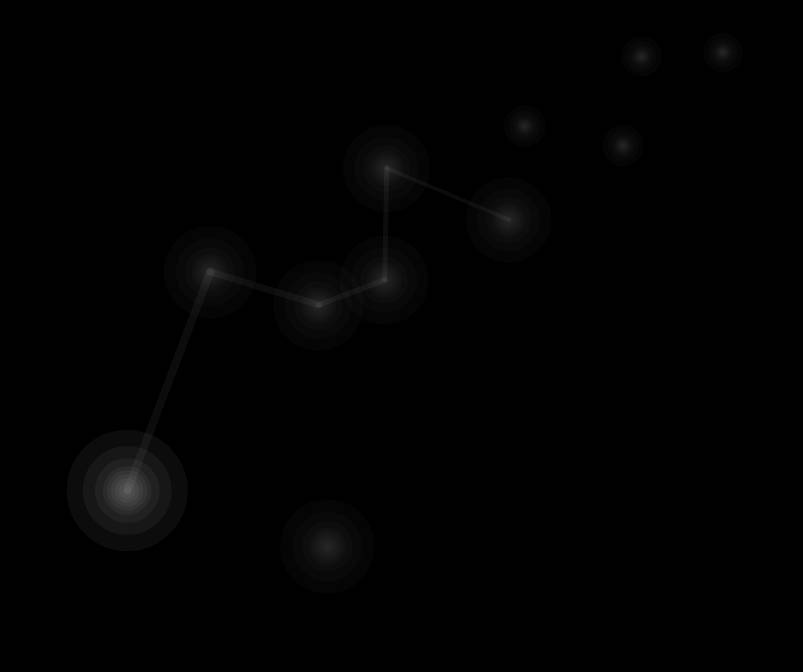

The idea of the mythical city is well-suited to the starry array that serves as the Night Haunts site map. From the opening page, what we see is a narrative constellation that makes its way through the night sky. The chart is different during each visit to the site: points are arranged across the sky in an ever-shifting line from beginning to middle to end. Each star that appears on the opening screen of the site represents a story. The string of these stars, as a new one appears each month, will eventually draw a line through the night sky of the screen.

Constellations, as we know from ancient myths, are groups of stars mapped over the night sky that create some sense and order out of an infinite multitude. Tied as they are to mythological storytelling, constellations are also a form of writing. They aren’t just random shapes drawn in the sky but actually organize the night sky into a text where myths are written and read, and move across the evening sky looking down from above. As shapes rather than words, each constellation stands for a character rather than a complete story. In locating Orion by his belt of three stars perhaps we can be reminded of his stories of heroic strength.

The same is true of the Night Haunts narrative series, but instead of looping back on itself in order to create a closed form like Orion or the Big Dipper, the Night Haunts project is a collection of unfurling narrative points without an end.

While Sandhu presents his constellation map as if each story lies across the night sky like a mythological technology, his work, I think, also maps a walk across London’s pitch-black nighttime topography. As a nocturnal flâneur, Sandhu writes his stories at the street level. After one chooses a point in the site map, that map disappears, leaving room for only Sandhu’s forays. His words emerge slowly onto the screen and emphasize their appearance, drawing attention to the darkness as they amble across the page. Under cover of darkness, the Night Haunts walk an irregular path through the city without references to the named streets, central squares, and magnetic monuments that mark out London’s familiar tourist landscape.

This is an episodic pedestrian narrative, its events presented in isolation, and there is no obvious link between the sites that Night Haunts visits. In other words, Night Haunts is a poetic topography, as opposed to a literal city map. Readers must create their own narrative connections from place to place.

In addition to the written stories, Night Haunts also includes visual and sound design components that open up London’s sensory presence. The city is not reduced to text. Instead, the text is complemented and read in concert with ambient visuals and sounds that sometimes work together, and oftentimes don’t, in order to create a livelier foray into the night. While Sandhu’s texts seem to describe a situation or place, the sounds that accompany it are more ambient and atmospheric. As for the pixels and images lying behind the text, they come into a nice proximity with the words in order to highlight their nature as overlaid and temporary components, part of an impermanent placement that will be written over, erased, then written over once again.

A palimpsest was a manuscript page that had had its previous text scraped off in order to be reused; sometimes the previous text could be still seen through the new one. This project is a similar palimpsest. Its layers of traces are metaphoric for the city that is written on: both as an inscribable surface and as the subject of a text. As we move through each page of Sandhu’s forays, the text does not remain for long before it is effaced by another page and new atmospheric sounds.

The critical difference between this piece and a palimpsest is that there aren’t any traces of the old text remaining to be read through what is currently on display. Sandhu is not working on an implicitly historical project of archeological recovery and sedimented narratives. His project is affective, akin to walking through the city with a miner’s helmet, shining a light on the city’s dark and tender corners.

When we click on the individual dispatches that Sandhu has written, how are they different from the other sorts of landmarks or stories that we normally use to understand or navigate through a city? Sandhu says that he will be “moving over newer nocturnal topographies”; Night Haunts explores the city of London via previously unexplored paths and locations.

In “Avian Police” Sandhu flies about the city in a police helicopter, spying on the people and buildings below. In “Night Cleaners,” he accompanies the semi-invisible street sweepers along their evening rounds in an elaboration of the English domestic worker tradition. In each foray, Sandhu positions himself within one of London’s nocturnal micro-communities and writes with them instead of simply looking at them.

Other forays describe a sensory topography that is woven into the physical geography of London. In “Loneliness,” Sandhu writes to chart the desperation and depression that circulates through the city at 3 am, “the hour of the wolf.” The Samaritan volunteers at a phone bank patiently tele-collect the loneliness that arrives from the city’s aching nerve endings, turning their Soho office into a sort of urban ganglion, attached to the outside’s wounds via phone lines.

There is still more to come. Night Haunts is an ongoing project. There are a few tantalizing clues to where we’ll find Sandhu over the next few months, but I’m sure we’ll continue to be surprised by London’s specificity and by its proximate virtuality.