New York Minnesota: Do You Have to Leave to Succeed?

A survey of a few photographers from the extremely vivid photo scene in Minnesota who have made it. Now that theyre a success, inquiring minds want to know: Are they going to move to New York? Alex Starace decides to ask...

For those of us who grew up in flat, open places, there’s a mythos to the Big Apple: The buildings are bigger. The people are smarter. The ideas are better – New York is a real place. The very streets are famous. (Park Avenue, Madison Avenue, Fifth Avenue, one after another: bing, bing, BING!) You can see celebrities. (Yesterday I saw Chuck Close in a wheelchair, smoking a cigarette out front of MoMA – it wasn’t all that big a deal, but, boy, it sure sounds cool!) Plus, New York’s expensive and far away. It’s dangerous (watch the purse!), competitive, and mean-spirited. Murders happen on a daily basis. Oh, and television shows are shot here. Senators and politicians visit all the time. It’s the world’s capital of finance, publishing, and fashion. It’s not for the faint of heart. … In short, as a Midwesterner, you come to believe that New Yorkers are better dressed, more intelligent, more worldly, and just out-and-out better than you are.

Of course, it’s not true. As much as New Yorkers might hate to admit it, there are as many narrow-minded, parochial people in New York City as there are anywhere else. The sort of people, who, had they lived in Nebraska, for example, could quite accurately be described as hicks. To newcomers, this is surprising: when I first moved here, I was shocked. Where were the super-humans? The eight-foot-tall men walking down the street in turtlenecks, sporting perfectly coifed hair and well-defined pecs? You know, the ones who spend their time discoursing upon Kierkegaard and his philosophical relationship to those glossy lipstick ads in Vogue? Those men?

…Well, it took me a while to realize that they don’t exist. But, once I did, it was with some amusement that I received an email from my editor suggesting I write a piece about how artists can “make it” in New York. A sort of describe-for-us-Minnesotans-how-to-succeed-on-the-ultimate-stage bit. Because the more I live here (it’s been a year now) the more I’ve become convinced that, aside from the obvious backdrop difference of scale (which includes the ever-present nodes of fame), the people here are mostly the same as people elsewhere. And, in some cases, succeeding in New York is actually easier. The city has an insane number of galleries, theaters and museums per square inch; basically, if you like cultural activities (and working in the culture field) it’s simply convenient to live here. But is it flat-out better? No, of course not.

In December of 2005 I wrote a review of the photography of the Upper Midwest. The exhibition I looked at, “Photocentric: A Photographic Biennial” at the MCP, had one rule: all entrants must reside within 525 miles of Minneapolis. The results were stunning and made clear that the Upper Midwest has some of the best photographers in the country. But what was most gratifying was that though there were a large variety of artistic styles, I could clump together several coherent aesthetic groups. And each group had a strong Midwestern ethos – the sort that made me proud to have grown up in Lincoln, Nebraska (a location within range of the project) and to have lived in (and loved) Minneapolis.

In the review, I say that “Brian Lesteberg’s Dad Field Dressing a Goose shows a man in hunting fatigues in the foreground, dressing a goose, while behind him, one can see seemingly forever – a few dusty roads cross in the far distance and open fields form a patchwork that one could imagine, from the height of an airplane, as a never-ending quilt dotted with silos.” The photograph still pulls my heartstrings; I’ve always been enamored with the history and vastness of the Great Plains. But, more to the point: such a photograph could not be taken in New York. And not just because there’s not enough space . . .

It’s not that Midwestern people are inherently different from those on the coasts, or that transitioning from one area to the other is cataclysmic. At core, each place has a similar range of the same sorts of people (though the proportional relations of these people may be somewhat changed from place to place). It’s just that there’s something different about living in the Midwest. It’s the physical space. The details. The day-to-day rhythms. The pace, the attitudes, the mode of transport, the busy-ness of the streets, the weather. The topography of the land and architecture, the types of food available, the smells, the history, the ethnic make-up, the public school systems, the local television channels, the available careers. These are what make the difference. A gradual accumulation of seemingly minor things.

So it seems a shame to not have artists live in a variety of places. Almost anywhere deserves some sort of sustained attention. In the exhibition “Photocentric: A Photographic Biennial,” that place happened to be the Midwest. And the artists in that show happened to be extremely talented. So if anyone has a chance of succeeding in New York, it’s these artists. Which makes them, conveniently enough, prime material for an article about transitioning to the Big Apple.

All sorts of questions abound: If they moved, how would their aesthetics change? Would they lose their ability to perform a careful cataloguing of the Midwest? I mean, in one sense, shouldn’t they stay where they gained their success? Don’t they owe that much to their fellow Minnesotans? Or is it fair to expect them to stay? Do they want to stay? Do they owe it to themselves to go to New York? And, hell: are they even leaving for New York? I decided to ask. I conducted email interviews with four of the six artists I mentioned in my review. The results were fairly emphatic: none wanted to relocate to Manhattan.

Two of the four recognized that, as Chris Faust put it, “it is still apparent that New York has a certain magic touch for one’s career.” But all the artists were skeptical about how to capture this “touch” because, as Chris Bohnhoff writes, “I don’t really understand whether finding success in New York or the Midwest is a matter of careful planning, target marketing, dumb luck, or a combination thereof.”

This sentiment isn’t bitterness. It’s merely the practicalities of the matter. Having lived in New York for only a year, studying and working for museums and galleries, already I can recognize that leveraging social connections, knowing the right people, and being in the right place at the right time are as important as being hardworking and talented. It’s not one or the other. You need both. Even the now-revered Alec Soth, a Twin Cities photographer who got selected for the 2004 Whitney Biennial and overnight became nationally famous, accedes to this. In a 2004 article written by Michael Fallon, Soth admits: “I know I got lucky. Just the fact that anyone knows who I am now is fascinating to me. That anyone in the photography world in New York has heard of me is a new concept.”

However, what’s lost in the midst of a discussion of ‘making it,’ is this: Soth, even after he was a big hit in the Big Apple, never actually moved to New York. A quick check of his homepage reveals that he still has his studio in St. Paul. Presumably he likes where he lives just fine, thank you very much. And this seemed to be the case with all of the artists I interviewed: it wasn’t that they were particularly intimidated by New York, or that they felt that they ‘weren’t good enough,’ to go there. They just didn’t see the need to move. Partially because it was too expensive, partially because it’s emotionally exhausting to pack up and move somewhere brand-new after having made lots of connections in one place, and, partially, as Martin Springborg put it: “I honestly love it here [in Minnesota] – for the place, the people, the culture. Not much would make me leave it.”

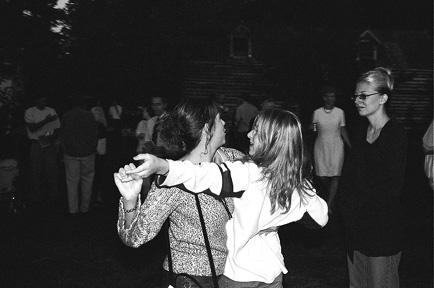

This attitude is evident in these artists’ work. Martin Springborg, according to his website, is continuing to photograph the St. Croix River (one of those photographs, Cabin Screen, appeared in “Photocentric”). He seems quite at home where he is, particularly in his series “Eliza’s Wedding.” In one image Eliza bends over a chafing dish of chicken wings, while looking ahead with a blithe, newlywed grin – someone off-camera is trying to tell her something witty. Behind her stands her husband Michael and an insouciant party-goer. Christmas lights form the trim of the shade-tent they’re under. The happiness is palpable, just as it is in another image – a scene where two women are dancing without having planned to. One woman still has her purse strung over her shoulder. But both seem amused. In the dusk-obscured background we can make out minglers and the roof of what appears to be either a barn or a house. The photo is gorgeous: a patch of trees in the upper lefthand corner reminds you of the pleasure of an outdoor party on a summer night. This is the Midwest.

Photographer Chris Faust also demonstrates a commitment to his locality. On the cover of his book Nocturnes, which was just released this year, is the Stone Arch Bridge taken from a low-angle shot that looks across the Mississippi towards lit-up downtown Minneapolis. The black-and-white nighttime air looks wintry and crisp. The city seems to be rising from the vanishing point of the bridge. This is Minneapolis at its best. However, some of Faust’s other more socially conscious work shows metro areas at arguably their worst.

His “Suburban Documentation Project,” which he completed between 1990 and 1996, does just what it claims. In one image, Development Approaching Apple Valley, MN (1994), we see that Apple Valley was once (not that long ago) fields and barns. Not any more. Similarly, New Development, Byron, MN (1993) is simultaneously uplifting and horrifying. There’s the hope of a few houses claiming the land: man’s ingenuity, technology, and spirit give us a domesticated and leisurely (yet slightly rugged) world in which to live. Though it’s hard to be too pleased when the inevitable looms: within a few years, cookie-cutter houses will cover the farmland, turning it into a tangled net of cul-de-sacs, tricycles, SUVs, and sprinkler systems.

While both Faust and Springborg clearly focus on Upper Midwestern geography, all four interviewees and I seemed vaguely uncomfortable with the nebulous, mostly-indefinable category of “Midwestern aesthetic” – classifications can be made, but not every artist fits. I suppose this is part of the problem with deciding that New York is the ultimate goal. Such a viewpoint implies certain hierarchies, which in turn imply certain categories. In this view, to describe and label something “Midwestern” is necessarily pejorative – the Midwest is lower on the totem pole. Moreover, the label becomes a catchall for everyone and everything from Minnesota. A way to ignore differences (and to ignore talent). Because we all know that no one in the Midwest (any more than in New York) is defined simply by where they live. Nor does every Midwesterner have the same interpretation of the topography around him or her. I mean, who’s to say what’s “Midwestern,” after all?

Chris Bohnhoff and Celeste Nelms (the other two artists I interviewed) make art that doesn’t immediately jump out as Minneapolis-based, even though each lives in the Twin Cities. For instance, Bohnhoff, with elegant, technically flawless images that abound in lush colors, seems to have a placeless aesthetic, the sort that’s defined more by its composition and its subjects than by any geographical or architectural features in the work. Unsurprisingly, then, he gets lots of solid assignments. (Including a trip to document Western Africa as part of the Sierra Leone Plymouth Partnership.)

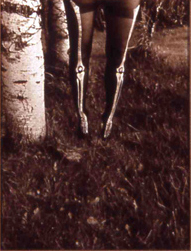

Compared to Bohnhoff’s universalism, Nelms’ work swings in the other direction. Her photographs are so personal (she includes herself in nearly all her images) and so specific (discarded manmade possessions placed in organic settings) that to say she’s a “Minnesota artist” is beside the point. She makes toned gelatin silver prints. With them, she creates a spooky olden-time world of ghosts, junky toys, child-like playing, and nostalgia. For example, the photo Stockings shows legs wearing skeleton stockings dangling down into the picture frame. There’s a birch tree to the left. And I wonder: the woman attached to the legs – Is she swinging on a branch, or has she hanged herself? …. Or maybe it’s Halloween? The photo’s in good fun, and yet it’s profoundly creepy. Ditto for her image, Sucker, in which Nelms, glassy-eyed, leans against a birch and looks off-camera. She has enormous, crooked, toy-fake teeth – and, well, the photo gives me the heebie-geebies. Her whole body of work does. There’s something so inbred, so personal and out-of-place about this woman, these objects, and these settings, that her photos are wonderfully mortifying and original.

Really, all four artists are fantastic – I could go on about each for a while. But what does this have to do with New York? And what does New York have to do with Celeste Nelms or Chris Bohnhoff or Martin Springborg or Chris Faust? I’m not sure. I guess the lesson about New York is this: if you want to move here, you can, but it’s not going to change your life or make you a better person. If you’re confident of your abilities and you want a bigger stage and more networking possibilities, a move to the Big Apple might be worth considering. But – and this is important – you can become a success or a failure in almost any location.