Native Son

When once-hidden details of Native heritage eventually come to light for later generations, people so assimilated they have come of age mostly oblivious to those roots, is there way to reconnect with that history and culture that doesn't feel false or, worse, like appropriation?

Mary Lethert Wingerd’s history tome, North Country: The Making of Minnesota, is a thorough chronicle of the state’s territorial era, with the Dakota War of 1862 as a tragic, definitive endpoint. While the full-blooded and outwardly Native population was alienated, ostracized, and eventually displaced, another group simply opted to redraw their bloodlines:

In the wake of the hysteria set off in 1862, Indian ancestry was not only reviled, it was also dangerous. Of those who favored their Euro-American forebears, many chose to invent a selective genealogy that expunged all trace of their Indian roots, often “vanishing in plain sight.” They blended into white society, some with more success than others. Suggestively, “French Canadians” radically declined as a percentage of the population of St. Paul in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Some simply anglicized their names to disguise their backgrounds, others migrated to ethnic enclaves like Little Canada and Centerville, just a few miles from the city, where they were not subject to whispers about their suspect bloodline.

My last name, “Patrin,” comes from a line of those “French Canadian” Metis, its pronunciation shifting over time along with the exact nature of its cultural origins. And for more than half my life, I never really gave much thought as to what that ancestry might mean or where it came from. That’s the kind of thing that comes to my mind whenever the phrase “white privilege” is brought up: being given the opportunity to pass, to downplay your identity for a bigger piece of that privilege, has to be one of the most culturally fraught ways of redefining yourself and your family’s future. And I wonder: When the details of that hidden heritage eventually come to light for someone of a later generation, somebody who’s been so assimilated that he could come of age mostly oblivious to those roots, is there a way to reconnect that doesn’t feel false or, worse, like appropriation?

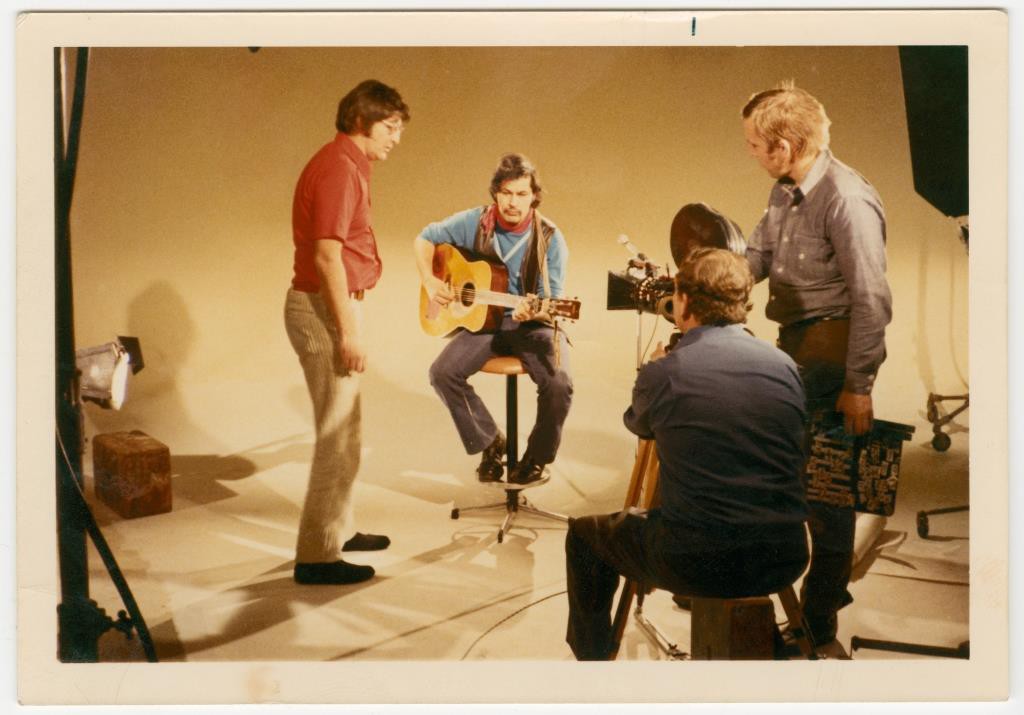

Willie Dunn. Photo courtesy of the artist and Light in the Attic Records.

The possibility for such reconciliation, or at least a route towards that possibility, might be found in the arts. And two current works drawing from Metis and other indigenous cultures, reflecting on their place in a contemporary North America, help make a case for restoring a living connection to those roots for people, like me, who are looking for one. Specifically, I’ve found some of those threads in two unlikely, apparently divergent forms: independent folk-rock music and custom lowrider bicycles.

Seattle’s Light in the Attic Records has been one of the best archival and reissue labels of the last ten years, largely on the strength of their ear for the underheard, from reggae recorded by Jamaican ex-pats living in Toronto to two volumes’ worth of country/R&B crossover. A notable, recent double-CD release — dropped, ironically enough, this past Thanksgiving Day — is Native North America Vol. 1: Aboriginal Folk, Rock, and Country 1966-1985. As much a miniature history book as a music compilation, the thoroughly researched collection is fascinating enough for folk and rock fans who long suspected that vein of cultural expression didn’t just stop with Buffy Sainte-Marie.

But there’s more to it than that. The collected musicians all pulled from their own perspectives as successors to a heritage constantly in flux, and that’s the deeper thread tying these pieces together. With a focus on Canada and Alaska, these musicians are representatives of many nations and cultures from above the once-meaningless International Border; many of them were brought up in boarding schools or otherwise alienated from their traditional heritage and looked to music as a way to find the route back and, more, a way to light that path, in turn, for others. Some of the featured artists came at it from the other end — they’re children of trappers or fishers or farmers who still had connections with the old ways but looked to these songs as new avenues for expressing them, after catching the sounds of Johnny Cash or Jimi Hendrix over long-distance AM radio waves. There are artists on this collection who sound like they’d fit seamlessly alongside Waylon Jennings (Ernest Monias’ “Tormented Soul”), The Allman Brothers (Willy Mitchell & the Desert River Band’s “Birchbark Letter”), or America (Brian Davey’s “Dreams of Ways”) according to the Canadian Content requirements of an early ’70s radio rock block. But they all come with uniquely First Nations’ perspectives, their songs speaking to spiritual and survival matters alike, with parallels to the conscious R&B and protest rock movements that swirled around the airwaves at the same time.

For me, two artists in particular stand out. Montreal-born Willie Dunn isn’t as well-known in the States as Leonard Cohen, but Dunn shares with the latter a home province, a multidisciplinary career, and a haunting baritone. And it’s through this familiar resonance that Dunn stakes a unique and powerful claim as a Metis voice. The compilation-opening protest song, “I Pity the Country,” contains jabs at the Hudson Bay company, colonial governors, and “saving-of-soul men” of the church; “Son of the Sun” dreams of peace and reaffirms the Aboriginal roots of his mixed heritage. Ontario-born Eric Landry later picked up on Dunn’s music — and his message: after being raised in a family that had severed itself from its Native roots, artists like Dunn and the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate musician/actor, Floyd Red Crow Westerman, helped Landry along in his drive to rediscover the beliefs and traditions of his lineage. The one commercial recording he released, in a career largely centered around live performance, was a 1985 acoustic number called “Out of the Blue,” which calls out the settlers Landry had once been raised to emulate: “I know you came here out of the blue/To this place, this land, this earth/You seem to think this place your home/Do you treat it well?”

That search for identity, sustainability, and connection with the old ways has carried over into a more contemporary urban environment, too, reaching far outside the reservations and into cities where those ancestral roots are more likely to be tangled, if not cut outright. Dylan Miner is an American Metis and working-class activist whose indigenous concerns are largely evident in the DIY, handmade ethic of his work, and particularly in his rejection of disposable consumption in favor of focusing on repurposing and maintaining durable goods. His traveling exhibition Anishinaabensag Biimskowebshkigewag (Native Kids Ride Bikes), on exhibit at the Weisman Art Museum through the first week of January, is an illuminating fusion of fashionable indie craft-culture artisanship and conscious cultural reclamation. It’s work rooted in indigenous cultures aimed at building stylish, functional modes of expression and transportation that also reach toward a guiding hand of just moral principles.

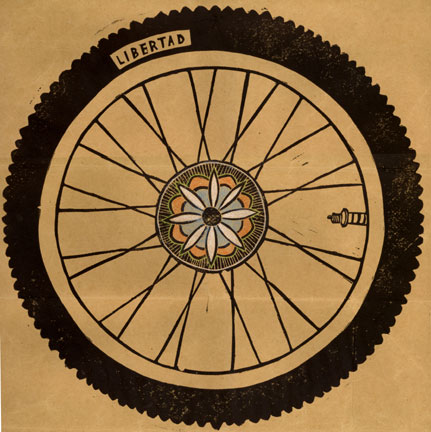

Dylan Miner, Native Kids Ride Bikes. Photo courtesy of the artist’s website.

In collaboration with groups of Native middle school and high school students, Miner oversaw the creation of seven different custom-made, lowrider bicycles to thematically represent each of the Seven Grandfathers’ sacred teachings in Anishinaabe culture: Wisdom, Love, Respect, Bravery, Truth, Humility, and Honesty. Given the number of Anishinaabe who once came to the urban cores of Miner’s home state of Michigan to work in auto factories, the Native Kids Ride Bikes project stands, in part, as a way to reconnect the younger, post-industrial generation with a self-built means of non-polluting, self-sustainable transportation. The resulting work is a cross-cultural means of expression equally indebted to the philosophies and craftsmanship of the indigenous Midwest, the Chicano lowrider culture of the American Southwest, and a contemporary hip-hop aesthetic of bright fluorescence and chrome.

Dylan Miner, bike detail. Photo courtesy of the Weisman Art Museum.

What it means to be indigenous in America, including what it means to be Metis or of otherwise mixed descent, is something that colonialist history has long tried to suppress and distort and shove into the footnotes of our nation’s official narratives. There’s a quote by Metis leader Louis Riel that Miner notes as a powerful motive for his art work, and as I’m looking to continue finding connections and inspirations in my own background, it resonates deeply for me, too: “My people will sleep for 100 years, and when they awake, it will be the artists who give them back their spirit.”

Related links and information:

Dylan Miner’s exhibition of lowrider bicycles created by urban Native youth, Anishinaabensag Biimskowebshkigewag (Native Kids Ride Bikes), is on view at the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis October 3, 2014 through January 4, 2015.

Find purchase information and listen to tracks from Light in the Attic’s newly released collection, Native North America (Vol. 1): Aboriginal Folk, Rock, and Country 1966–1985, on the label’s website.

Nate Patrin is a lifelong Twin Cities resident currently residing in St. Paul’s Uppertown neighborhood. He has written about arts and culture, particularly music, for over 15 years, and also counts graphic novels, film, and visual design among his many aesthetic interests. His work currently appears in Pitchfork, Wondering Sound, Greenroom Magazine and elsewhere.