Turtle Theater Collective: Storytelling as Connection

A conversation with Ernest Briggs, artistic director of the Turtle Theater Collective, on nomadic practices, collaborative models, and cultivating spaces for Native artists

Arguably the oldest of artistic practices, theater and live storytelling have a rich history of creating alternative art spaces, whether in radical theater communes—where lines between performing arts and life blur—or in roaming troupes. Founded in 2016, the Turtle Theater Collective is a Twin Cities–based group dedicated to supporting Native performers. Founding member Ernest Briggs traces how the tradition of nomadic storytelling continues to shape and inform art and life in the Twin Cities.

Jake YuznaCould you introduce yourself and the Turtle Theater Collective?

Ernest BriggsSure, my name is Ernest Briggs, and I’m the artistic director of the Turtle Theater Collective, started in 2016 by Marisa Carr, Sequoia Hauck, and myself. The collective’s focus is on supporting Native artists and telling Native stories in a modern context or reimagining old classics.

Early on we wanted to reimagine Shakespeare with all Native American casts, to give young Native performers a chance to be cast as leads in a Shakespeare play, which very rarely happens. Another goal was to employ Native persons behind the scenes, such as sound designers, set designers, costume designers, stage managers, and directors. To give opportunities not just for actors and writers, but also to all roles and crafts in theater and performance.

In addition to reimagining classics like Shakespeare and Our Town, we also performed new works, like Larissa FastHorse’s What Would Crazy Horse Do? and Almighty Voice and His Wife by Daniel David Moses. With Our Town, the Gibbs family was all Ojibwe actors, and the Webb family was cast with Dakhóta performers. In addition, we organize a series of workshop readings as well as an educational program.

During the pandemic, we started a partnership with the Guthrie Theater that helped us expand our educational focus. This is allowing us to do something really important to me, which is inspiring and educating the next generation of Native performers and Native artists. At the same time, we held a lot of workshop readings that aim to cultivate Native writers. These readings and workshops were all held over Zoom, and this fall we’ll be having live performances for the first time in almost three years. That’s really exciting. In November we’re going to be doing Marcie Rendon’s play Say Their Names and This Way, Yonder by Montana Cypress, which will run for about two or three weeks.

JYHow did the collective start?

EBMarisa Carr and I were very young performers and writers living and working around the Twin Cities. We had talked about starting a theater company or a theater collective together. We decided on a theater collective because it allowed us to also expand what we did into a lot of different areas of live performance, like theater, dance, and performance art. We landed on Turtle Theater Collective as the name, which was something that we were really proud of at the time. But, mostly, the idea to create a theater collective was born out of a need to re-envision the classical theater canon to include Native storytelling and artists.

We also wanted to bring forward new works of the Native theater canon. Plays like What Would Crazy Horse Do?, a great play by an amazing playwright in L.A., Larissa FastHorse. I was lucky enough to be a part of the workshop readings of it, and then we ended up getting the rights to perform it here in the Twin Cities at the Mixed Blood Theater. It was very well received by the audience. It’s a very challenging piece.

But, ultimately, Turtle Theater Collective was founded out of a need to cultivate the next generation of Native performers and Native artists. To create an outlet for Native performers to work in many different ways.

JYWhat were the experiences you encountered that led to the creation of Turtle Theater Collective?

EBBack when Marisa and I were young Native performers, it was pretty standard that if it wasn’t explicitly said that a character was Native American, the role was probably going to go to someone who is Caucasian. We wanted to create opportunities where Native performers and artists could perform a Shakespearean monologue, a Greek monologue, or any other kind of role that wasn’t readily available at the time. Without the chance to perform in those kinds of roles, and more modern roles, they would have a really hard time getting cast in other plays and performances. At the same time, we wanted to make more opportunities for plays from the Native canon to be presented to the public more regularly. To give Native artists a chance to stretch their legs and do different things. We essentially were founded as a way for Native artists to stretch themselves and get the opportunity to do amazing things that nobody else would cast them in.

JYCould you talk a little about some of these newer plays the collective is working on?

EBThe Marcie Rendon play Say Their Names is about missing and murdered Indigenous women. This is an epidemic that’s been going on in this country for many years. I’ve been trying to get a play written or produced about this for probably five or six years, since we started Turtle Theater Collective, because it’s very close to my heart.

Montana Cypress’s play This Way Yonder is about a family set in Southern Florida within a Native tribe. I don’t want to give too much away, but it is a very funny comedy. Montana Cypress is an amazing writer and I’m happy we get a chance to perform that piece this December.

JYFor readers who are not familiar with the Twin Cities and Minnesota, could you give a little context to the Native community here?

EBMost of the tribes in the southern part of Minnesota are Dakhóta and Lakhóta, and the tribes in the northern region are majority Ojibwe. I am Ojibwe and an enrolled member of the White Earth Nation. I also grew up in the Twin Cities, so I am what some might call an urban Native. That isn’t a bad thing. I self-identify as it.

There are also a lot of Native people who are very much intertribal. There are numerous tribes, not just Dakhóta and Ojibwe people, although those are the vast majority in terms of Native populations that exist here in the Twin Cities. And we have tons of places here that people can also embrace. There’s the American Indian Center, which has been a great place for people to come together and work on various projects in various capacities. There is the Division of Indian Work as well, just to name a few. It’s a very rich, vibrant community that stretches across the entire state.

JYHow is the collective structured?

EBWhen we started Turtle Theater Collective it was mostly organized and run by myself, Marisa Carr, and Sequoia Hauck, who left for New Zealand shortly thereafter. It became Marisa and me running the collective and making decisions on a lot of things. Then Marisa left to be a full-time writer in Chicago a couple of years ago. So that left me in charge to be the sole artistic director right now. Currently, a lot of the decisions run through me right now. (Laughs.) I would love it if we could have more people join the collective and add more leadership and new ideas.

JYDo you have a group that you work with?

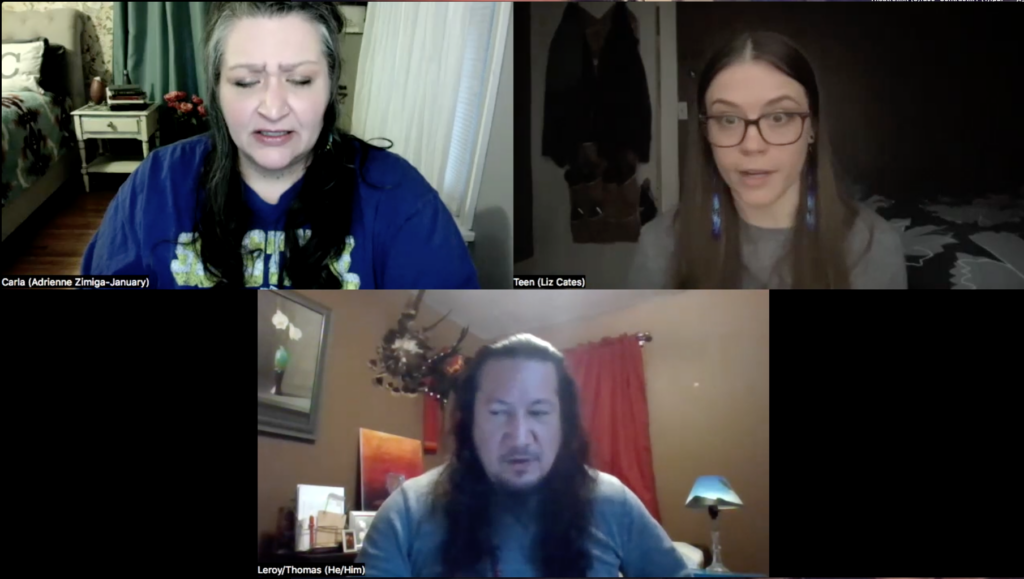

EBThere is a roster of performers and artists that I collaborate with regularly, including Katherine Pardue, Marisa Carr, Ajuawak Kapashesit, Roy Taylor, Brian Joyce, Kirby Hoberg, Elizabeth Cates, Addrienne Zimiga-January, Jei Harold-Zamora, Katie Johns, Nathaniel Two Bears, Kholan Garrett-Studie, Thomas Drascovic, Montana Cypress, and Larissa FastHorse.

JYHow do you view how the collective is structured in comparison with traditional theater troupes?

EBI don’t think of us as a theater troupe model. That term makes it sound like we’re going from town to town and putting on plays. I like to think that our model is a little bit different in that we collectively consider what types of plays and performances we are staging as well as how they are made—who is working behind the scenes as much as who is on stage. We put a lot of effort into the due diligence of making sure that our way of working supports Native artists in all aspects of what we do. It is more than just staging a play. That’s important, but only the last part of a deeper process.

Because of that, I try as best as I can not to follow a traditional theater model when it comes to the rehearsal process. I like more of a circle mentality, where everybody has a lot of input. I’m very familiar with the standard theater format, and I know that that can be very effective. But I thrive in an approach where everybody can throw in an idea, and then we see what’s working and what isn’t. Maybe we try something out and, even if it doesn’t work, it’s good that we tried it. (Laughs).

JYDid you choose to be nomadic and not have a physical space, a theater that was your own, or was it by necessity?

EBWhen we started, we really liked the idea of being semi-nomadic. We knew that our artistic home is right here in the Twin Cities. We could perform at all kinds of venues, like Southern Theater, Playwrights’ Center, Mixed Blood Theater, and the History Theater. Although it was partially by necessity, it was very helpful for us, especially when we started. We didn’t have to worry about the costs and other factors of having our own space. I’ve always actually kind of enjoyed being nomadic, and the Ojibwe people were semi-nomadic. They moved with the seasons. There is just something about it that works.

I like being able to go to a new venue and say that we can perform here, or there, or anywhere. It doesn’t have to be in one place or venue. It also allows us to reach people who wouldn’t expect to see theater and performances by Native artists. I’ve had people approach me after a performance and say, “I wasn’t expecting to see What Would Crazy Horse Do? at Mixed Blood.” That was a treat. I’m always happy to be a surprise for people. It allows us to embrace flexibility, not being stagnant in one place.

JYYou mentioned that the founders of your collective were proud of its name. Could you speak about its significance?

EBThe easy answer to that question is Marisa Carr is a member of Turtle Mountain. When we were sitting around the table working on creating the collective, we couldn’t come up with a really good name. We kicked around a few other ideas, but since our founding idea was centering on Native artists, Marisa suggested Turtle Theater Collective. I said “Oh my gosh. That sounds really good. Where’d you get that?” She said, “I like turtles.” (Laughs.)

But the turtle is a symbol of wisdom in a lot of Indigenous cultures, as well as in my own. A lot of people know the story about the earth being on a turtle’s back. But there is more. There is a lot of respect and reverence for turtles because they have a lot of wisdom. They do things with a lot of patience, and that is how our theater collective operates. It just fit us in a lot of ways.

JYYou mentioned working with the Guthrie and other kinds of official art spaces. How have those relationships been beneficial to an alternative group like yourself?

EBThe partnership with the Guthrie has been beneficial mostly because we get to advise on what is happening within the Native community. We can create opportunities for members of the Native community to travel to the Guthrie and see performances and take workshop classes they wouldn’t normally get a chance to do. We offer free classes through the Guthrie that are taught by Native performers or Native artists. For instance, we recently had several students travel from White Earth travel down to the Cities and see a show at the Guthrie and have a workshop. A lot of them said that it was a great experience. It is an opportunity for Native kids to discover that it is possible to be a performer or work in the arts.

Cultivating the next generation of Native performers is important to me, and our partnership with the Guthrie has been very beneficial to that. I’m also a member of the Native Advisory Council at the Guthrie, which allows us to open up dialogues about a lot of issues that are going on in the Native community. They’ve been very generous to us in terms of donating rehearsal and performance space. I can’t even begin to tell you how helpful that is. Especially when the cost of rental spaces and performance spaces are the biggest item in a play’s budget.

JYDoes the collective engage in other performance art forms, or do you center on theater specifically?

EBRight now, we mostly focus on the theater productions we have coming up in the next six months. But I just had a grant come across my desk that might make it possible for us to bring touring artists here to the Twin Cities and work with venues that do some forms other than theater. For instance, there is a Native dancer from the Carolinas we’d love to bring to the Twin Cities. We’ve also always wanted to partner with performance artists and see if there’s something we could do together. We’re moving towards expanding what we do.

JYWith such a rich history of alternative spaces organized by artists working in theater and other performing arts, a history that goes back hundreds of years, I was curious what your thoughts are on why this is such a part of performing arts’ DNA.

EBThe simplest answer is that everybody all around the world has stories to tell. If you don’t see stories of your people and your experience being performed, or you don’t see yourself being represented on stage somewhere, artists go make it.

I got this advice many years ago: “If you don’t see it, you should write it and put it up somewhere.” A lot of people have embraced that model for many years. Recently, there is even a new wave of it happening with a lot of different theater companies, organizations, and collectives popping up. It’s because they don’t see themselves, the way they experience the world or the work they want to be doing, represented anywhere else. You have to create your own opportunities.

The reason you see a lot of this kind of thing in the Twin Cities is because we have a lot of great artists here who 100% understand if there’s not that opportunity for me, then I’ll go make it happen. You can do a Fringe Festival show, or something outside in the public, or wherever. Those are all great ways to start your theater collective or theater company. One of the really beautiful things about the Twin Cities is we have a great arts community. It boils down to the need that we have to tell stories. I’ve started every class that I ever teach, whether at universities, high schools, middle schools, or at the Guthrie Theater, by explaining that I’m a storyteller. If I wasn’t doing this for a living or lived at another time in history, or if I was living a tribal existence in a small village, I’d be the keeper of the stories. I’d be the one telling the stories. I was always amazed when I was young and would hear my elders tell stories. I would see the people telling those stories act them out. That was my first introduction to theatricality. Turtle Theater Collective is what allows me to tell stories. Everyone has that need for stories, and I think that is in the DNA of theater and performing arts.

JYOften people from outside of the Twin Cities don’t realize how big a theater town it is. People are familiar with New York or L.A., but Minneapolis often comes in third for theater in the country. Do you have any thoughts on why theater is so rich here?

EBThe beauty of the Twin Cities is we like to do experimental theater. We like to experiment with art. Things that you wouldn’t normally see in other places. We fund and create interesting opportunities for people to be artists and share that with the world. I have yet to find another place like the Twin Cities, and I’ve lived in Los Angeles, Florida, Chicago, and other places. The Twin Cities has a great community that supports one another. If someone loses their lighting designer or costume designer, the community comes to their aid: “I know so-and-so who would be perfect. Let me help you out.” That sort of thing.

I’m not saying that’s not the way it is everywhere else. I’m sure it is, but it just feels like in the Twin Cities we understand that we’re helping everybody to succeed.

JYDo you have any advice or recommendations for anyone who might be interested in making their own theater performance group or collective?

EBStart writing. (Laughs.) For me, that’s always the hardest thing. I have the patience to perform. I have the patience to direct. I don’t have the patience to write my own scripts. (Laughs.) Writing is hard. It has to come from a very truthful and honest place. You have to be comfortable with turning that work over to other performers and saying, “I’m going to step back and let you interpret the work in a completely different way.”

Then start small. Put on a small performance, maybe 30 minutes long. I always like to name-drop the Minnesota Fringe Festival because a lot of theater groups have gotten their start there. You can get a venue and a chance to perform for five performances, and possibly more if your show sells well. That is a great place to start and then build up an audience of people who want to see the work that you’re performing.

If you decide that a troupe or collective is something you want to do, then it becomes a question of what kind of group you want to be. Do you want to be fiscally sponsored? Do you want to be a nonprofit? How do you want to operate? Do you want a leadership model that has a hierarchy, or do you want a collective model where everybody weighs in on everything? These are all important questions to ask yourself when you are starting. The better idea you have of what you want to create, the easier it will be to do it.

JYWhat role do you think performance and theater have in a larger arts community?

EBI have always believed that art reflects the world we’re living in, the society we’re living in. You should see art and have a reaction. It should elicit a response that you didn’t have before.

For instance, years ago when I was living in L.A. I saw a dance performance by two older dancers in their 50s. The piece was called A Marriage. It had no words. The female dancer walked forward and dropped with all of her weight to the floor. The other dancer would catch her before she hits the floor. They kept doing this. Over and over. That’s always stayed with me. At the time, I wasn’t married, and now it’s funny because I realize that sums up marriage. (Laughs.)

That work has always stayed with me from the time that I experienced it. Now, as a person who’s been married for almost ten years, it resonates with me much more. That is the beauty of art in any form. It can reflect the society you live in while eliciting a reaction deep within you because it’s either something you never noticed before or something that you’re not paying attention to.

If it is eliciting a response in you, then you should do something about that response. If the work being performed in front of you angers you, makes you like feel something needs to change, then hopefully it can lead to that change. If it excites something in you or makes you see something from a completely different perspective, that’s not a bad thing either. I think we should all walk away from the art we view with a different perspective. What is unique about theater and performing arts is that you’re with these artists live—together in a room, or outside, or wherever—having that response in real time with other people. It spreads out and can affect change or make an impact on other art forms.

It goes back to storytelling. With storytelling, you have the opportunity to express something very personal in a way that makes a connection between people. Theater and performing arts are just one form of that history of storytelling. It’s how we connect to one another and pass on who we are.

Ernest Briggs also recommends: