Messy from the Start: Birth, Breastfeeding, and Abjection

Representations of pregnancy and motherhood in A Glitter of Seas, the inaugural exhibition at Dreamsong

Dreamsong is an exciting new development for the art scene in Minneapolis. Opened in the former co. (company projects) space run by Cameron Gainer, it now sports three beautiful galleries, one of which is a stunning screening room. In its inaugural exhibition, A Glitter of Seas, Rebecca Heidenberg curates a robust and accomplished group of women artists who explore the transformation that maternity has made on their lives. Heidenburg mixes the likes of Nan Goldin and Frida Orupabo with Julie Buffalohead and Nicole Havekost, all of whom hold court on equal footing.

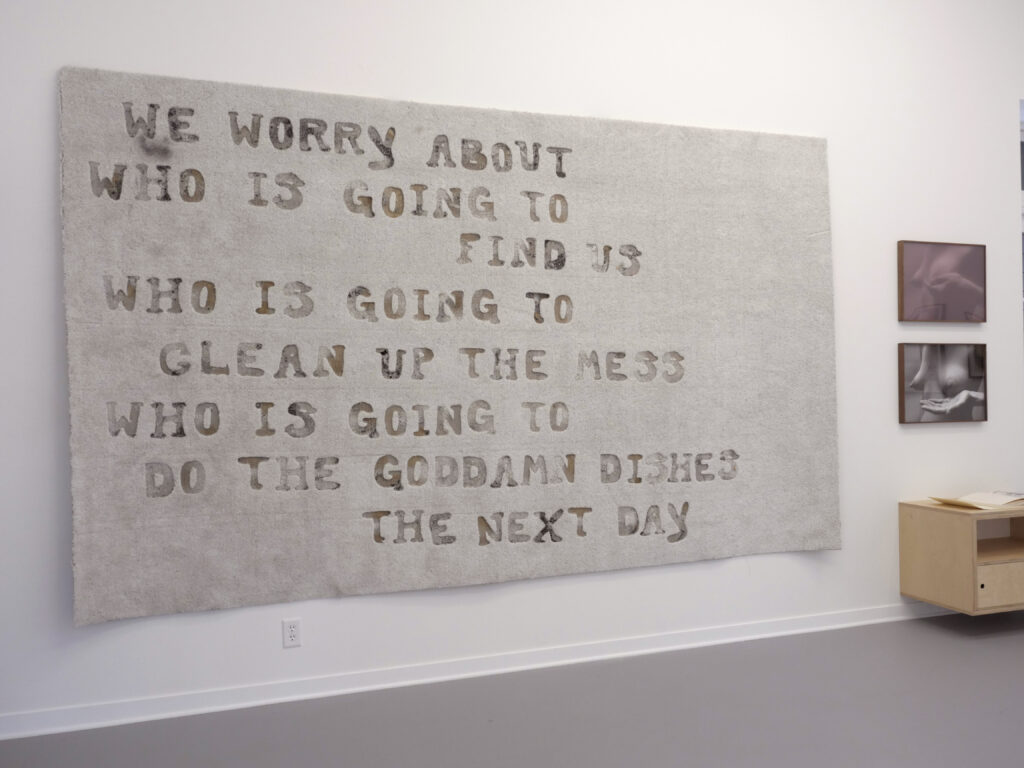

Little representation of the mother in art and visual culture comes from the aching source, the actual complex and conflicting experience. These representations typically exclude the taxing bodily experience of pregnancy, birth, and breastfeeding, the exact activities that A Glitter of Seas reveals in unflinching rawness. Maternity is messy from the very start and the artists suffer and revel in it, from bloody birth to leaky breastmilk and unkempt spaces. Take Allison Baker’s Night Mother, where large, all-caps letters burnt into an 11-foot rug convey a tragedy of the everyday domestic, including anxiety, fear, and isolation, still burdened by the need to get everything done. The branded hide of the rug is in concert with its text: “Who is going to find us / Who is going to clean up the mess.”

The show both begins and ends with the protruding bellies of full-gestation pregnancies, emitting feelings of exhaustion, confusion, hope, and hilarious monstrosity. I have gone through three pregnancies and births, and I will never forget the strange and unsettling sense of my body being taken over by this other thing, the absurdity of losing control and giving into the process of human-making happening inside myself. That unsettled sense of self permeates the show, reflecting on transformation both physically and psychologically. A large Nan Goldin photo of a bikini-clad woman resting on her side, Rebecca at the Russian Baths, NYC, is not the reclining female figure of art history. She seems tired, resigned but happy, as the belly takes over the focal point of the gaze, while the yellow- and green-speckled mold around her similarly gestates regardless.

The photo is visible as you enter the gallery through the arc of the neck of Burrow, a large soft sculpture of a pregnant being with its head buried by Nicole Havekost. This commissioned work for the show is created in Havekost’s characteristic style of muted felt, frantically sewn with red stitches while hooks and eyes scramble up the neck of its subterranean, missing head. Burrow expresses a body made more whole by its many scars, towering an arching passageway through to transformation. As the body gestates, it feels like a fracture into a million pieces that then come together in a different pattern.1 Both Burrow and the video piece Chewbacca by Laurel Nakadate, shown in the screening room at the end of exhibition, omit the identity, becoming all about the pregnancy. Where Burrow buries their head as a way of dealing with the feelings of uncertainty about what is to come and how their life will change, Chewbacca thrusts the belly out proud, bold in her monstrosity, united in force with the power of a sci-fi creature: she roars like Chewbacca.

How do breastfeeding and art go together? By creating the fluid of art, breast milk becomes the art material sourced directly from the artist’s body. Abjection is the interior becoming exterior, the presence of bodily fluids, captured by the artist’s hand and by the camera in Melanie Schiff’s photos Waxing and Waning. She displays the typically objectified breasts as leaky and utilitarian, holding her hand below her breast she catches the expressed milk as it falls. Across the gallery, Breastmilk Watercolours Series plays with the messiness of boundaries between the artist self and the artist-born child, between the inside and the outside of the artist’s body. Amy Wong collaborates with her child Rudi, who smears the watercolor crayon in playful assuredness, while mom uses her breast milk to blend and mix.

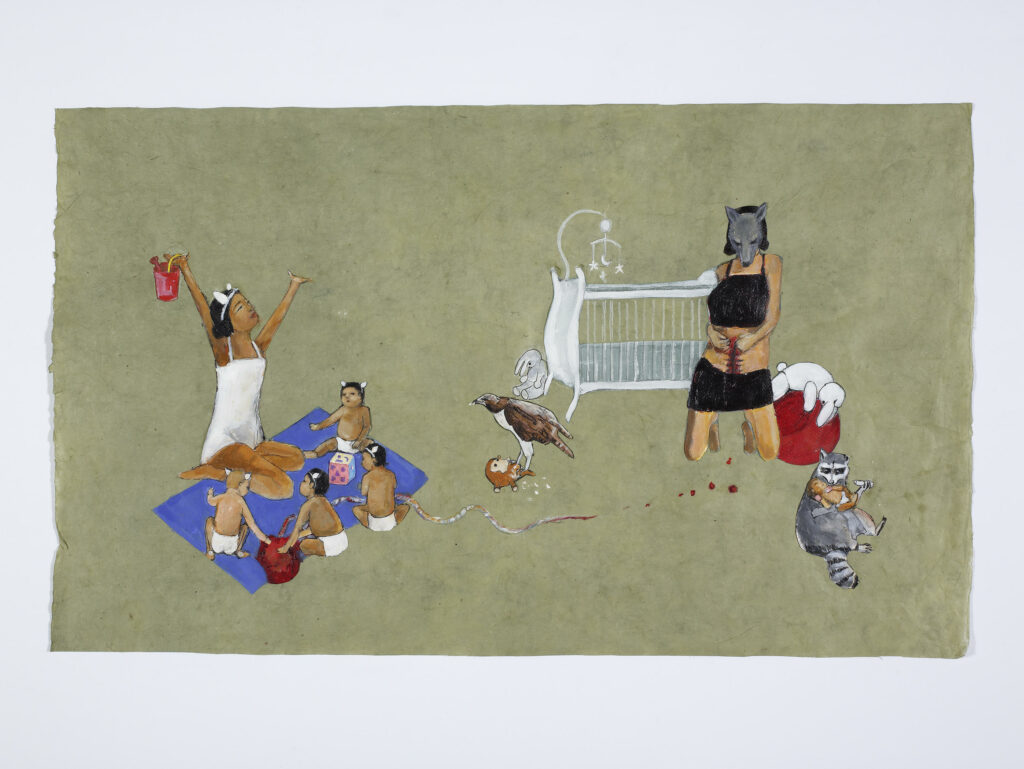

There is a specific tone intentionally set for the exhibition, Heidenberg tells me. The tone has an underpinning of grief and darkness that harkens the pain of postpartum depression and of loss caused by miscarriage or abortion, mostly private and hidden events on the maternity pathway. Julie Buffalohead presents in Mother Superior a wolf-masked woman who rips open the bloody seam on her belly with animal guardians around her, brave but exhausted, caring for the lost child. Laura Nakadate superimposes her new baby onto photos of her late mother in The Kingdom Series, a heart-wrenching take on generational loss. Loss is a subject touching many due to the cataclysmic events of the last year and a half. A mother’s loss in Minneapolis, a son’s last word, “Mama,” becomes a worldwide rallying cry of maternal care and outrage against police violence.2

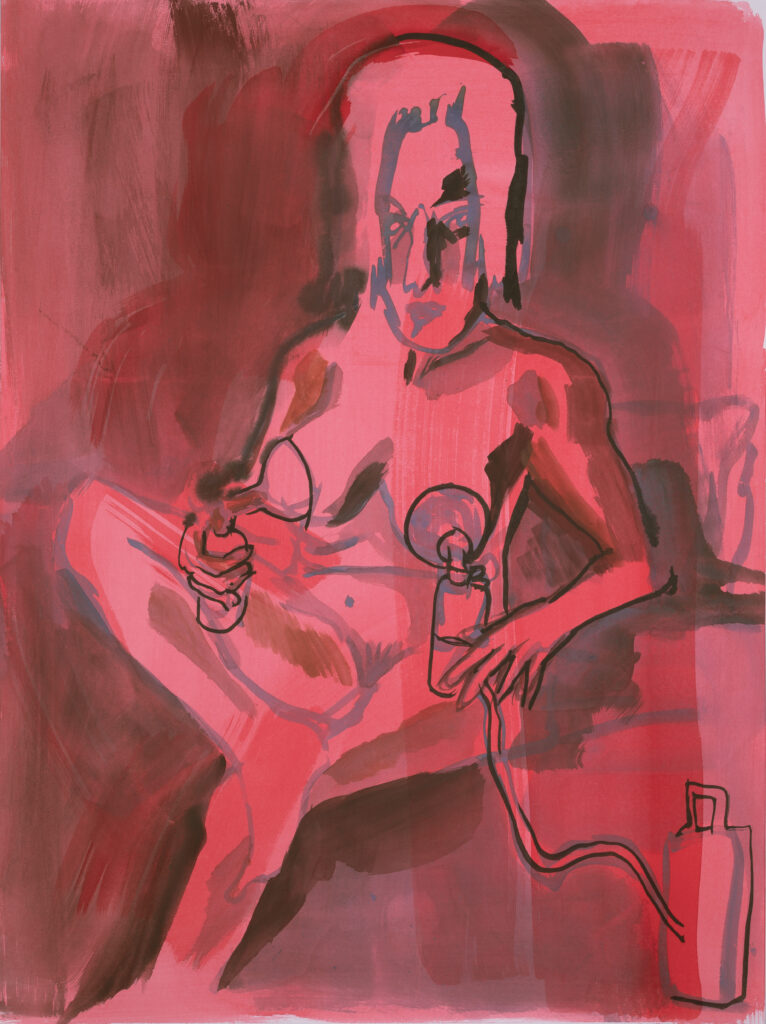

Loss can also manifest as the loss of a discrete sense of self and identity, as one emerges from the ashes of an intensely painful and bloody birth and months of sleep deprivation; from caring for a newborn and waiting for a moment to create art in the studio. Camille Henrot, internationally acclaimed for her work on maternity, chooses to co-opt the absurd abject reality of her body as milk producer and baby maker. She offers in Wet Job 1 a blunt, ridiculous, punk rock and raw, naked mama with the milk machine hooked up to both breasts in the red light of the midnight hour. I find myself internally chuckling with the feeling: “Yeah, that’s what it feels like when you’re the milk machine!” It’s the way she crosses her legs with the ankle on the opposite knee, casual and matter-of-fact, her elbow confidently leaning on a surface beside her. It screams of the monstrous and the menial, the abject absurdity of pumping milk from your own body like a cow, and the sounds of the machine bellows in the red paint—such an annoying sound. Overjoyed, of course, to have been given the gift of a newborn, but befallen with the change of the embodied self into heifer, she might as well own the new capabilities of the physical self, tap into the new power of her body to lactate.

“I wanted to try to dismantle the expectation of the ‘good mother’ and think about motherhood as a state in which contradictions, ambivalence, and inner conflict could arise and be acceptable.”3 Henrot’s work is serious in the way that it reveals the issues at stake when the mother is seen as an endless source of “soft labor,” producing a consumable item like milk that can have real dollars attached to it. The labor of mothering has never had a value within the patriarchal, capitalist structure that designates worthiness. This fact is taken up by Sarah Irvin’s work exhibited next to Henrot, which tackles the magnitude of the labor involved in meeting the hunger needs of the baby by keeping track of the feeding times at which breast, left or right. It is part of a much larger project, Infant Feeding Log, where she fills out a bureaucratic time log for her feedings with an X stamp. In Stamp X No. 13, Irvin lets the X of the endless logging of care duties for baby run wild and fill the page.

The need continues for art attuned to a more complex maternal experience. That makes an exhibition about the mother’s interior life—as much as domestic life—cutting edge and timely, especially considering COVID layoffs and the real needs of children due to lockdowns. Many mothers have been stripped of earning potential outside of the home and have “regressed” back into unvalued domestic labor. I can relate to this situation a little too well, as I, like others in the art world, lost my job due to COVID. I wonder how many were mothers who, like me, were told that their layoff is for the best, “because your children need you.” Having been re-domesticated by the pandemic, returning to the home 24/7 with my children, brought me back to the baby years, when I was breastfeeding while pregnant and had a six-year-old running around. I am stuck at home again with endless cleaning, feeding, and tending to emotional needs (of my now-school-age kids) and their constant interruption. I feel unheard, unseen, unvalued in this role, striving in crevices of time to do my “valuable” work outside of mothering and the home. Spending time in this exhibition, where I was immersed in the messiness, tenderness, and true grit of my maternal life felt like a relief! Here was the sigh of finally being in a space in which I felt understood and relatable. Heidenberg says she has heard this from quite a few mother visitors.

A Glitter of Seas runs through August 8, 2021 at Dreamsong, 1237 4th Street NE, Minneapolis, MN 55413, dreamsong.art.