Gravity Happens to Us

Nicole Havekost on felt bodies, healing process, and taking up space

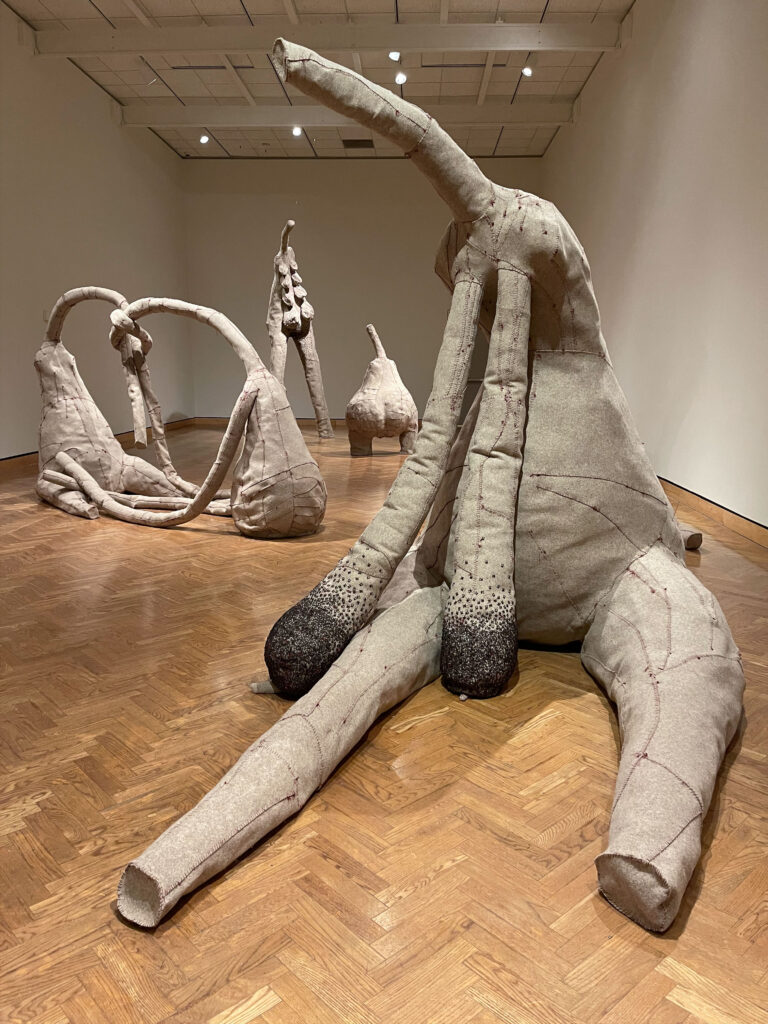

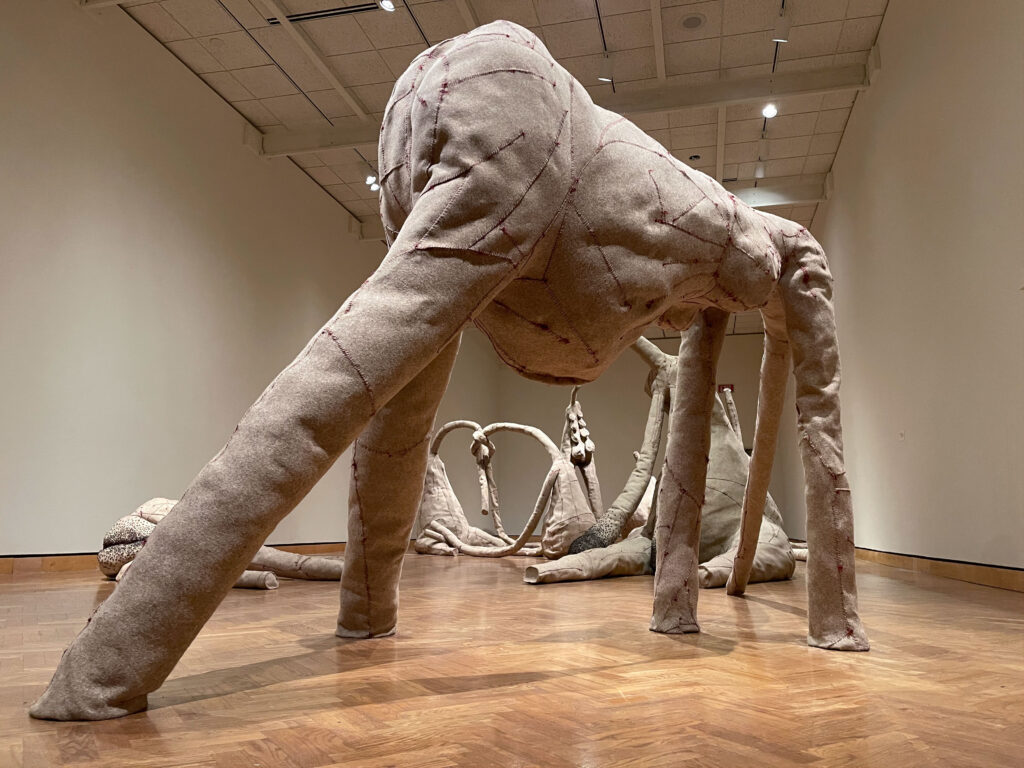

Nicole Havekost’s giant, knobbly creatures loll about the Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program gallery like the gentle urRu or Mystics from Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal. The exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, called Chthonic, referencing ancient gods of the underworld, unleashes the force of feminine power grounded in the earth.

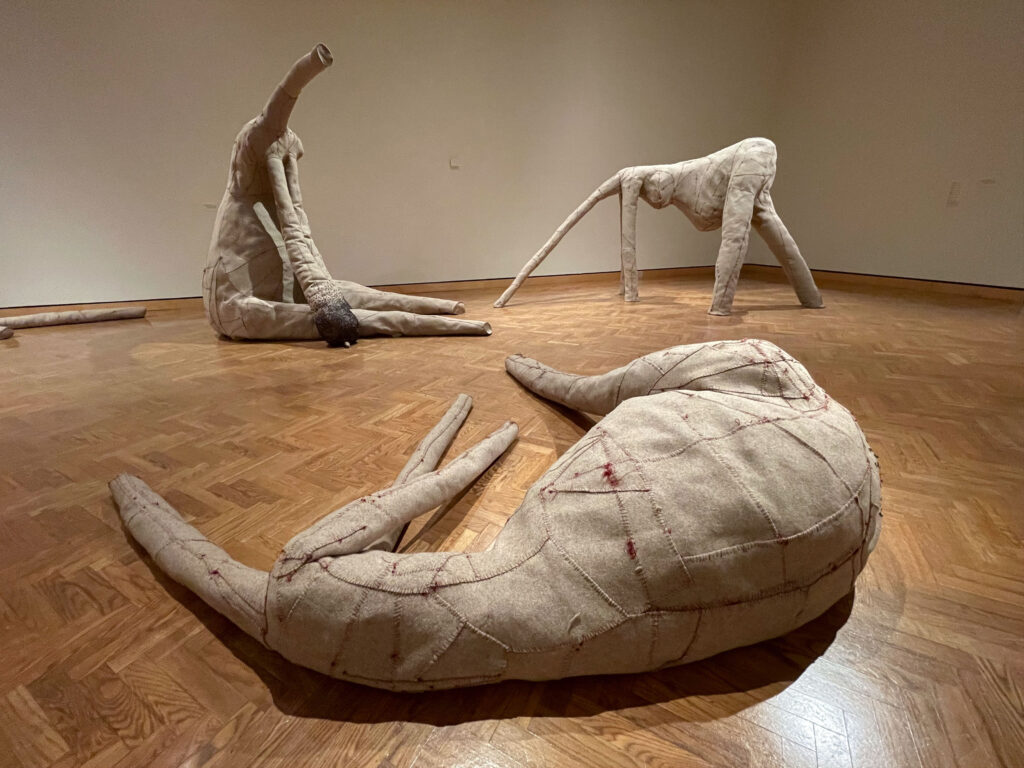

The headless, digit-less beings make camp in the gallery, their elongated limbs stretching out languorously, asserting themselves in their displays of comfort, care, and community. They are both animal and amoeba, genderless and distinctively womanly, with their wide hips and drooping breasts.

One figure’s arms wrap around her body in a nurturing gesture and stretch past her torso, looking like legs. Some are adorned with sewing hooks and eyes, others have multiple udders, and all of them have the red stitches that hold them together prominently displayed. Looming near these figures is a display of bulging forms that have the feeling of deflated body pieces hung for display. It’s as if Havekost is intent on showing the construction of her creations: warts, stitches, bulges and all.

The startling work came out of Havekost’s interest in the human form, particularly as a woman who has had her own, sometimes antagonistic, relationship with her body. Here’s a conversation with the Havekost, who lives and works in Rochester, Minnesota, about the work.

Nicole Havekost, Chthonic (2021). Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Nicole Havekost, Chthonic (2021). Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Nicole Havekost, Chthonic (2021). Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

sheila reganDo you feel like the decision to make these sculptures so big is because of the space in the MAEP gallery, or were there other reasons that went into the decision?

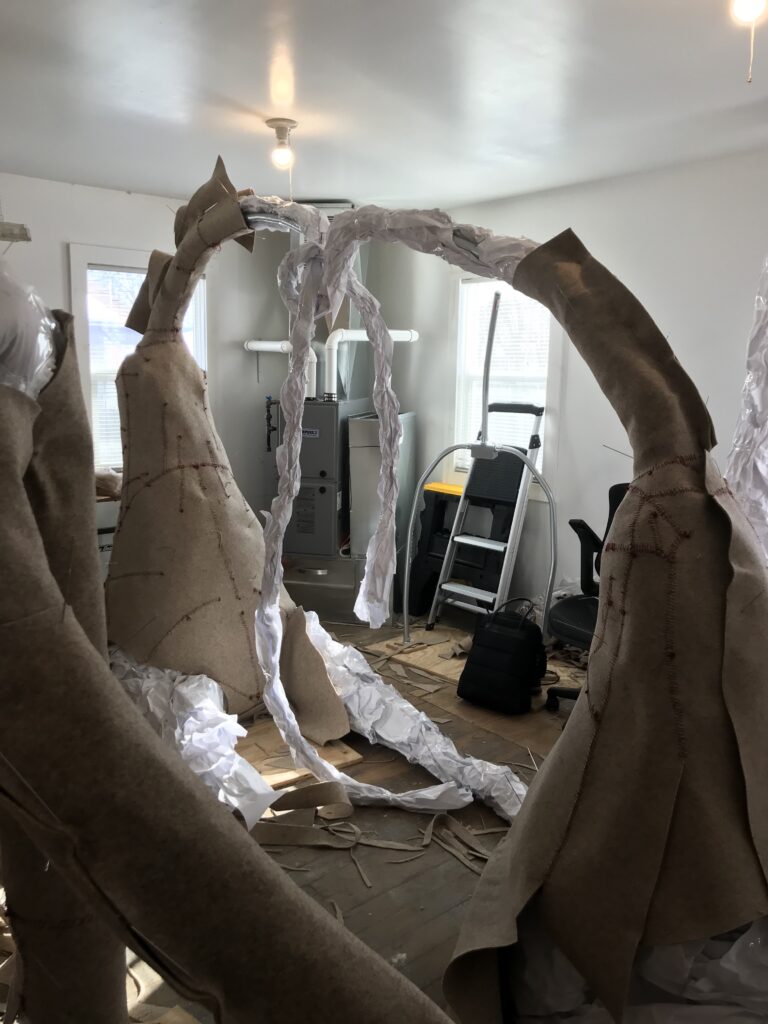

Nicole HavekostIn my proposal, I was figuring six to 10 feet tall, because I thought that makes them at least as tall as us, if not a little bit bigger, and I thought that would be enough. And then once you start going big, there’s no going back. Some of it I actually didn’t see put together until it was in the space because my ceilings in my studio are only eight feet tall.

The space really inspired just how much room they could take up. They could just really hold space in a way that my work has never done before.

srWhat did you discover, making work this big?

NhIt’s super fun, and I’m probably ruined for anything else. I came to sculpture accidentally, so I kind of have imposter syndrome. I don’t know how to use saws and fire things. I just sort of figure it out. Nobody’s done it before. There’s no right way to do it, so I just make it work.

SRWhat draws you to this notion of femininity, or the feminine body?

NHIt’s personal experience. I just turned 50 this year. I don’t know that I would have been capable previously. I spent my whole life trying to manage and maintain and control and manipulate my physicality. To understand that your body is yours, but it’s also something else, took me a long time to come to.

What is important about this work is that we can have certain desires and expectations of our body, but it’s an organism in and of itself, that has its own desires and its own means of maintaining, regardless of what you do and don’t want for it.

This organism is so familiar, yet so animal. There are all these expectations wrapped around it, like what it’s supposed to do, who’s supposed to be for—and then to sort of reconcile what that is for you in particular, and what that is for the actual physical form.

SRI noticed none of them have heads. What was the reasoning behind that?

NHI did try to put a head on one of them and they became almost too human. I needed them without heads—they’re still a little animal, and with the heads it just made them too human. I felt like I had to deal with the face and features and facial gestures, and that’s just not what they were about.

I get that it’s that it’s kind of violent—but I also don’t think that their gestures are aggressive, so that helps.

SRThey all kind of all have similar shapes, with very large hips, and sort of the thinner waist. They’re all pear shaped. Is that something that you do intentionally?

NHIt’s kind of the body shape that I’ve always made. Although it’s totally not realistic, it’s exactly how I see myself, even though I know that there’s a disconnect there. But yeah, it’s also very motherly.

Nicole Havekost, Massed (2021). Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Nicole Havekost, Chthonic (2021). Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Nicole Havekost, Chthonic (2021). Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

SrThe barnacle-like forms on the wall, are they kind of like a counterpart to the figures?

nhYes, and in my original proposal and thoughts about the work, I figured that the large ladies would also have some of these on them. So one of the pieces that I made for another show was a torso with one leg, and she had these basically as udders down her torso. I was thinking that they would become a part of this other body. Once I had the felt bodies built, they didn’t need them. I just couldn’t get them to feel like they were part of the part of the same body.

SrDo you do you see this work as feminist?

nhI think so. For me, it’s just really like owning this body that I live in, and celebrating it, and all of the beauty and grotesqueness that comes along with it. These guys could just take up space without any apologies, and also with no expectation.

SrThey’ve kind of got a little community going on. They’re playful. Did they ever communicate to you in some way, when you were working on this, especially in the space?

NHWhen they were in my studio, they were all really on top of each other, and for you to get through the space, you had to duck under them, and scooch through them to get around, so they were really a whole group or community in my studio space.

And it was funny—when I had a friend build the MAEP gallery to a small scale, so that I could make little figures in there to see how much work I wanted to have, I showed it to my husband, he was like, “Oh, I didn’t expect that,” because we only knew them right on top of one another and intertwined with one another.

I really loved how snotty and hairy and slumpy they were. They just kept becoming more and more who they were.

At first, I was really disturbed because the felt stretches, so the one with the long arms that wrap around it, she’s kind of puddling on the ground, and that really bummed me out. But it’s what happens to us. Gravity happens to us.

Chthonic in progress. Photo: Nicole Havekost.

Chthonic in progress. Photo: Nicole Havekost.

Chthonic in progress. Photo: Nicole Havekost.

Chthonic in progress. Photo: Nicole Havekost.

Chthonic in progress. Photo: Nicole Havekost.

srYou talked earlier in the conversation about becoming older, and how that’s allowed this space for reflecting on the female body and body image. What it is about getting older that frees a person from those negative thoughts?

NHThere’s no other option. The only other option is death. I have no other option but to live in and love and be proud of this body—because the other way is so uncomfortable and so useless. It’s not an okay way to live.

I used to be a real athlete. I’m to the point now where I need my knees to work. I decided that my back not hurting and not exercising is a place that I’m ready to live in, as opposed to having horrible back pain, but being muscular and skinny. To come to the understanding that I can’t stop any of it has been really freeing.

To just recognize that my body is worthy of kindness and respect and empathy—for a long time, I didn’t believe that to be true.

Nicole Havekost, Chthonic (2021). Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Nicole Havekost, Supine (2021). Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

srHas this project been a source of healing for you? Or did you already do your healing, and this is you reflecting on that?

nhI think it’s more that I already did the healing, and that let me make this unbelievable work that I would have been too afraid to previously— to make work that was this ugly. It’s also beautiful, but I would have been afraid to make work that was this unedited, or this raw, or this lumpy, with all of the knots.

srAnything else you might say about your experience with this process?

nhIt was really a blessing to sort of divorce yourself from the ego and from all the feelings about the work and the quality of the work. How do you go about making this thing, the best thing possible, and use all the resources you have available to you? It’s still amazing to me—I can make the things that I think of. That’s just such a gift.

Nicole Havekost: Chthonic runs January 28 through June 26, 2021 at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2400 Third Avenue South, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 888-642-2787, artsmia.org.