Manifesto: Why I Love Small Independent Theater

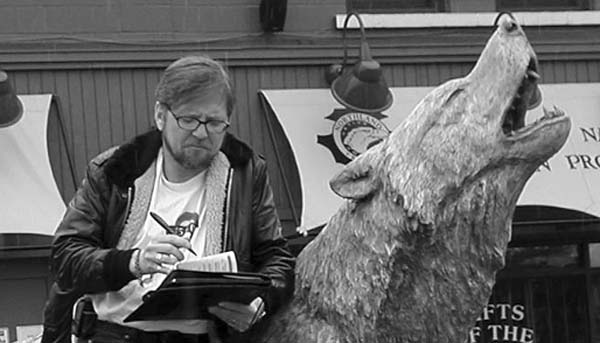

Dean Seal, familiar to any fan of performance and theater in Minnesota, is our newest columnist, joining Michael Fallon and Andrew Knighton. He'll write once a month on issues in performance in this space: The Column.

I work in live theater because I love it, and I love it for a number of

reasons. Money isn’t one of them. There isn’t much money to love.

In New York, they say that you can’t make a living in theater, but you

can make a killing. Here it’s the opposite. In this medium-sized market, you can make a living in the theater if you treat it like a business in which art happens, and if you’re a generalist who can act one day and direct the next, stage-manage this show and sweep up after that one. Not a place for the proud or the perfectionist, just a place for those who want to immerse themselves in the process.

This is a good thing, because a lot of stuff in New York City is bad

stuff. Poorly written, poorly acted, poorly staged, because there is so much money to be made that people aren’t thinking about the play, they’re thinking about the money. In LA, they’re thinking about an agent that maybe will come. And probably won’t. There’s some good stuff in LA, but if you ask anyone out there,they’ll tell you it’s not a good theater town; theater is something even actors don’t go to, because if they’re out seeing a show, it means they aren’t working the next morning, and it makes them look bad.

Writers are tempted to do anything but write for the stage. There’s a

lot more money to be had writing bad scripts for television and movies, scripts that stay in development; that never get shot; or get shot and never aired; or get shot and aired but never seen; or shot, aired, and seen but immediately forgotten. Twenty million people may see your mini-series tonight, but by next Thursday it will have evaporated. Even successful writers fear for their professional lives every day, because programming is so skewed to young markets that still watch TV and are still influenced that producers’ basic tenet is Don’t Trust Writers Under 26.

Theater is different because it respects experience. Experience means you’ve already made a lot of mistakes, and can be counted on not to repeat most of them.

Theater is different because it involves people in a collaboration.

Everyone puts something personal into the performance, because that’s the only way it can work. Even the most dictatorial director, one who tries to enforce “one vision” for the show, goes away after opening night and turns the show over to those who are running it.

Theater is different because you don’t need a million bucks to do a show. You can start by gathering a few friends in a room to read a script out loud. Bain Boehlke of the Jungle Theater recommends to any young theater artist to start a reading group and read a bunch of plays out loud, and talk about them, and when you find a script that is so exciting to everyone in the room that you have to put the show up– that’s when you start a theater company; when you have something you have to do.

This is a great and overlooked strength of theater, that a lot of very

good work is done by amateur companies — “amateur” in its old meaning, “amat-eur”: people who do it because they love it. The Guthrie and the Ordway have very expensive bombs in any year’s calendar; many amateur companies have best work that rises above the top theater’s worst. You can find an $8 ticket that sends your heart and mind rocketing over the moon, and you can walk out of the Big Taj Mahals feeling angry that you wasted the night, the money, the parking fee.

Theater shares with movies the gathering of people into one space to

experience something together. It goes beyond movies in that you are sharing the experience with the artist, and this is a crucial difference. We are confronted with the artist, which is good. We have a chance to contribute because we respond. All theater is interactive. The performer needs something back from the people he’s doing the show for, or he might as well do it at home by himself.

An audience that gets it can send the actors into a pure heated vibration of power, of the joy of effectively communicating something valuable to people who understand what is being said and done and told. This is a vibrant, magical moment for everyone in the room, no matter what price or what pedigree.

I love the theater as an audience member, as a presenter, as a performer and aspiring playwright. I love it as a box officer, janitor, and concession salesperson. Whatever the contribution is that makes a good show go up and find an audience is a valuable contribution.

The isolating technologies of computers, cars and television do whatever

they can to keep us from talking to each other. Joe Dowling at the Guthrie hit the nail on the head when he described a good theater night as having “a secular spirituality” where something sacred takes place because we are together, and it has nothing to do with a religion or a creed or a belief; it is just the experience itself, the two-hour binary symbiotic creature called an audience and a cast, that come seeking each other a the appointed time, co-mingle across the footlights, and come out feeling that their life is richer for the experience of hearing a story from today or a thousand years ago, where we can connect with people through the ages or across our own table.

Theater to me is like sex, in this way: even a bad night is pretty good.