Lots of Feminist Blockbusters: Kiki Smith, Diane Arbus (Especially), Eva Hesse, Kara Walker

Suzanne Szucs takes note of the great shows by women artists the Walker is doing this year. Kiki Smith and Diane Arbus took their turns earlier; Eva Hesse's drawings are up now and Kara Walker is upcoming. Enjoy the view from the other half of the world!

Last year I wrote a column bemoaning the lack of women artists represented in major museums throughout the country (see “I Want My Feminist Blockbuster”. I promptly received an email message from someone at the Walker Art Center taking me to task because there were, apparently, lots of femme events coming up. Duly noted. The Eva Hesse exhibition opening this weekend is just one in what has been a stellar series of shows by great women artists. Kara Walker has a major retrospective coming up as well.

In my reply to the Walker person I promised to take note. I hereby acknowledge that the Walker, at least, is doing its part in trying to create more equity in its exhibitions. Kiki Smith’s work was not relegated to the basement, after all: it sprawled throughout the main galleries of the original building. Frankly, it was luxurious, and that Smith is still alive and wandered about the galleries herself during the opening made the exhibition that much more celebratory. My experience of solo shows for women in major museums has seemed too often to be Mary Cassatt and Mary Cassatt and, oh, Mary Cassatt, who was a fabulous artist and deserves every show dedicated to her, but appears to be the token female from the nineteenth century exposed by institutions still hell-bent on exploiting Impressionism and Post-Impressionism for all they can make it worth.

The WAC quickly followed up the successful Smith show with a deep retrospective of the work of photographer Diane Arbus. Curated by Elizabeth Sussman and Sandra Phillips at the SF Moma, and then traveling to various museums (WAC was the last stop), the exhibition, “Revelations,” is quite the production and most certainly falls into the blockbuster category.

The question then arises, why Arbus? Does one have to have had a sensational life (and death) to warrant such status? A feature film starring Nicole Kidman (“Fur: An Imaginary Portrait of Diane Arbus, “ 2006) is testimony to her magnetism–and if one can judge by the trailer, the film definitely looks to be a “portrait” of the thrilling side of Arbus, not particularly about her work. Touché!, you may well remark; as Arbus made her fame through photographing the outsiders in our society, it seems only fair play that the camera should be turned upon her. That Arbus seemed most comfortable with that demographic, and that each portrait reveals something about Arbus, is incidental to why the general public enjoys looking at the images – for us, unless we penetrate further, our interest remains an obsession with “the other.”

Arbus is one of the most important image makers of the twentieth century. The exhibition (and its catalog, a book available in the Walker store, even though the show is now down) was thorough in taking the viewer on a pathway full of the incident that enables a viewer to read this. For my part, I was thrilled to see so many images that had been hidden away. As a student of photography, I had seen many Arbus photographs over the years, but it was wonderful to see her trajectory – many images from her early years, experimenting with technique, trying on her interests. I first went to view the exhibition on the WAC’s free Thursday and it was packed with viewers of all ages. It was extremely gratifying to see the power of photography – its hold upon viewers’ imaginations.

Arbus’s view of the world represents a juncture between the abject and sublime. Coming out of the fashion industry (where she originally worked in partnership with husband Allan Arbus – later better known as an actor playing psychiatrist Sidney Freeman on “M*A*S*H*”) as well as high society, where her exposure was to the rich and famous – what we might call “the beautiful” – the exhibition makes clear that her own gaze looked toward the margins, away from this center. At first stealing glances, she eventually confronts her subjects with such transparency that she exposes her own vulnerability, her need to touch them with her lens. Her intimacy is so complete in a number of her images that speculation as to the true nature of her relationship with her subjects always accompanies her work. It’s like watching a car crash – we like the sensational.

Is that sensation what makes Arbus good? Absolutely not. That’s all us – we place that upon her. Arbus is the great empathizer. Past the “freaks” (aristocracy, she called them, because they were born with their trauma), we see that it is our individuality that interested her. She doesn’t set out to make us ugly but rather alive, and the peculiar to her is beautiful. She craved connection and exploited the vulnerability of her subjects, understanding that this is what makes us human. Our vulnerability is universal, but in today’s hypersensitive society, expression of it is rare. I wonder if Arbus, focusing so heavily on difference and outsiders, would have been able to make this work today.

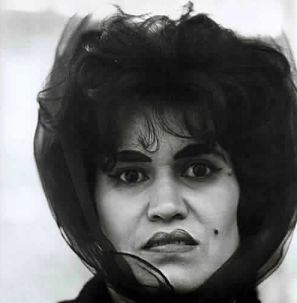

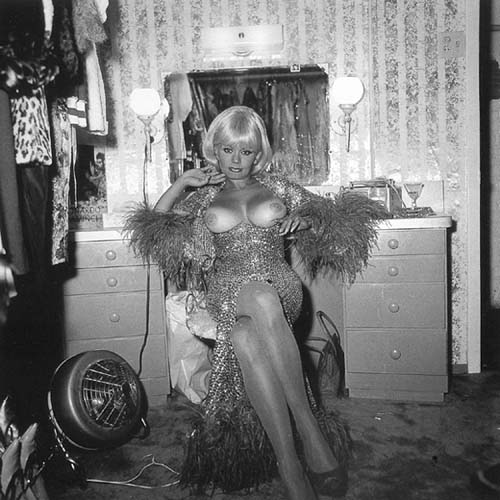

During an era where masking was so common, Arbus’s work is extraordinarily informative. Her photographs of society functions reveal a culture loaded with artifice – women coifed and codified into mannequins – and these images stand in contrast to a topless dancer sitting at ease in her dressing room, her bare breasts made even more naked by the surrounding suntan lines that expose their whiteness. She is comfortable in her own skin. The curators set this image next to one of a groom aggressively kissing his bride; cross-dressers inhabit the space next to teenage society ballroom dancers. What is more natural, searching out and expressing one’s true self, or enacting the codified experiences of social life? Arbus the ethnographer has gotten too involved to see clearly and she pushes and pokes at them all, forgetting what group she has come from. Side by side what we have been taught is the abject and the sublime flip and, indeed, in Arbus’s care the “Puerto Rican Woman with Beauty Mark” (my personal favorite) becomes royalty.

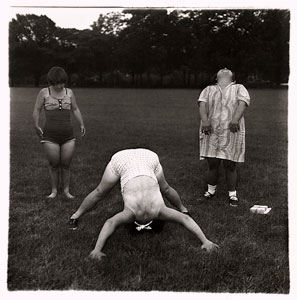

Arbus is the ultimate chronicler of how we behave towards one another – what we want, how we love, how we see ourselves. She documents what it means to be human from a cultural perspective, documenting American ritual, so it is important that she photographs groups of people breaking the rules as well as obeying them. Her photographs of nudists are perhaps the most comfortable that she ever made. The formal aspects of the images are softer – lighting, printing, composition are all a little less aggressive than much of her other work. Many of them act as pastorals, drawing on iconographic portraiture, yet without clothing. It adds humor, not at the subject but at our conventions—a lightness sometimes lacking in Arbus’s other work.

Her last extant project, photographs of mentally retarded women, is by far her most lyrical and tender (her own words). Arbus was constantly in search of herself; these women, so blissfully unaware of their difference, of their “condition,” are not. They are what they are. This runs counter to everything Arbus had been exploring in her mature work. The mentally retarded women are mostly masked, which connects them to the themes of artifice that Arbus had been exploring; for once, though, these masks are playful. The women demonstrate their freedom from the constraints of society through their lack of self-scrutiny.

What kind of revelation did Arbus experience in witnessing the contradiction of liberation through ignorant bliss in these institutionalized women? In the inevitable quest to find out why Arbus at the height of her powers would have committed suicide, perhaps these photographs are the clues. Perhaps here she had finally found what she was looking for… but is that really important? What is crucial is that the work touches us at the most basic level – it has the potential to turn us all into empathizers, something desperately needed here and now.

The tendency in blockbuster exhibitions is to marry the myth to the artwork. This show went beyond necessity to reveal the artist behind the photographs. The exhibition featured several rooms of chronology, personal memorabilia, journals and letters. I found these rooms overdone and distracting. Yes, this is interesting material and does contextualize some of her work, but so much of it is better left to the biography or biopic. Seriously, you’ll find everything you need to know about Diane Arbus in her work and I believe that is how she probably would have wanted it. Her needs, her desires, her vulnerability, what she had to communicate are all present in the images she made. That’s why she made them. Will we never expunge the modernist impulse from the museum and stop treating artists as if they are from another planet? Perhaps that is what brings in the viewers, or delineates a “blockbuster,” I don’t know. On my second visit, I wandered through the galleries, close up with the art work, close up with Diane Arbus, seeing what she saw, feeling the vulnerability, the specialness and sameness of us all.

The Walker Art Center will be featuring the work of Eva Hesse and Kara Walker in upcoming exhibitions. Keep it up!

Read what the WAC has to say about the Arbus exhibition:

http://calendar.walkerart.org/canopy.wac?id=2683