LITERATURE: Writer, Interrupted

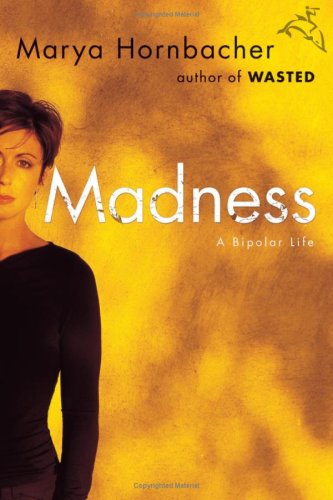

Nationally acclaimed author Marya Hornbacher talks wtih Hannah Dentinger about her new memoir, "Madness: A Bipolar Life," which offers an unflinchingly candid glimpse into a life periodically upended by mental illness.

ONE DAY IN 1997 MARYA HORNBACHER RIFLES THROUGH the phone book, looking for a psychiatrist. Any psychiatrist. She settles on a Dr. Beedle. A man named Beedle, she reasons, cant be all bad. Later that day, Hornbacher perches on a chair in Dr. Beedles office.

What brings you here today? he asks.

Im going crazy.

Well, dont beat around the bush, he says. Jump right in.

Hornbachers new memoir abides by that maxim. Madness: A Bipolar Life begins smack in the middle of an accidental near-suicide, and the reader is swept away instantly in the streamno, the torrent-of-consciousness that characterizes a manic episode. Its a scary, yet exhilarating ride. And it comes closer than anything Ive read to capturing the complex, messy totality of anothers mind.

Ive had a lot of letters from people,” says the author, “from family and friends, librarians, teachers and school counselors, and from psychologists and psychiatrists, telling me this helps me see inside my patients. Hornbacher uses innovative techniques to document the chemical events taking place in her brain, such as algebraic formulae If (X) Dr. Grau is here + (Y) I am here, then (Z) it is all right that, she tells me, express an attempt to slow down thought and make logic happen where there is no logic; it’s the kind of thinking that I often do, and that many do, when I’m in a speeded state.

Her evocative prose envelopes the reader, both in form and content. Manic passages are peppered with exclamation points, and they bend and sway on the page in a rush of italics. The punctuation reflects how Im thinking, Hornbacher explains. When I try to reflect manic thinking in my writingthe forcefulness and speed and the run-on sentencesmy brain starts speaking in exclamation points. Yes! Yes! She chuckles. Yes, yes sounds contemplative. I dont mean that. I mean mad! In the initial stages, she concludes wryly, I have a hard time putting in periods.

As a writer, Hornbacher is necessarily fascinated by words, by nomenclature. Bipolar disorder has replaced manic depression as the preferred term for the illness from which she suffers, but she tends to favor the almost quaint designation of madness. It was Dr. Beedle who told Hornbacher she was bipolar. She was 24, and although she had been exhibiting textbook symptoms of the disorder for years, her condition had somehow eluded diagnosis. Her immediate, circular thought was All that time I wasnt crazy; I was, in fact, crazy.

Hornbachers family and friends have adopted her rather unorthodox terminology. She explains, Theres a movement of people who would like to be referred to as “mental heath consumers.” But when Ive climbed up on a cabinet in the corner of a triage room and [my husband] Jeff tells the doctor, shes crazy, thats more effective and efficient.

Is Hornbacher making a conscious effort to reclaim words like crazy and nuts, in the same way that a word like queer has been adopted as a term of pride? She assents, but adds, It is not a militant desire for everyone to adopt the term crazy. I got one email from a woman who said, I detest the title of your book. But I do not feel ‘mentally disordered,’ I feel crazy. It feels like the loony bin when I go there, not the ‘hospital’. Hospital, she elaborates, is a sterile word, an antiseptic word. The psych ward is not sterile and rigid. Its disorder itself. I am using my language for it.

Ironically, language is the first thing to be affected by the onset of a spell of mental instability. Hornbacher evokes the approach of mania:

I feel my mouth filling with words, words I need to write down right now,

and my mind begins to race, words whirling in circles, a cyclone of words….

But I dont write the next day…. Because sometime during that night, the words

scattered. The whirlwind of words, beautiful strings of sentences, which I pictured as a

net of letters, strands of words spun into a kind of silver sugar cone inside my

head, whirl away from me, phrases and snatches of words now seething all

over my brainpan like a pit of snakes.

This mix of metaphors mirrors the jumble of her manic thought. Ideas blur and morph, the transformation takes place too quickly for Hornbacher, herself, to keep up. The writing is intimately affected, although not necessarily tied up with bipolar [disorder], she explains, refuting the tenacious stereotype of the mad artistic genius. I cant particularly write when sick. Cohesive narratives come when Ive reached a state of balance. During a manic spell, Im writing garbage. When madness comes, when my brain leaves the room, the words are the first thing it takes on the way out.

For Hornbacher, writing also constitutes a matrix of identity and self-esteem: My self-worth is bound up in my ability or inability to work, more so even than in the quality of the work I’m doingI have more investment into whether Im creating [at all] than in whether what I produce is good.

This ties into a thread running through the entirety of Madness: the idea of making it, of measurable success. Hornbachers acclaimed first book, Wasted: A Memoir of Anorexia and Bulimia, was published when she was only 23; after Wasted, she went on to be nominated for a Pulitzer, to win awards for her journalism and teaching, to publish a well-received novel, to be a fellow at Yale.

In spite of these achievements, she reveals in Madness that she has been plagued by a lifelong feeling of failure. Because, no matter what other people might think when they look at my life, I cant see, have never been able to see, anything like success. It doesnt matter what I do, what I publish, what the critics say, what people tell me. None of it feels like mine.

Hornbacher anatomizes a terrifying sense of being an imposter in her own life, stripping her own wiring bare as she describes the feeling that I am getting away with something, living a life I don’t deserve. Its someone elses life. Ive snuck in and am squatting in it. Im wearing someone elses wedding ring, occupying someone elses house, and everyone loves the woman I’m pretending to be, not me.

The intimacy of passages like these is startling, even more so than her matter-of-fact accounts of episodes of brutal self-destruction when under the influence of alcohol and mental illness. Hornbacher acknowledges, I come off as confident and together to people who dont know me well. She describes the process of revealing the extent of her self-doubt in her new memoir as gut-wrenching. Its like admitting a horrible guiltsomething very, very hidden in myself. Writing Madness was harder than Wasted, in a way. Most things are harder when youre 34 than when youre 22, and being honest is one of them.

Madness sometimes reads like an attempt to puncture that confident exterior, to deliberately expose what Hornbacher calls the quivering mass of insecurity inside, even to invite condemnation. I think what Im trying to do, more than anything, is to poke a hole in the perception that people have of mental illness, she says. Mentally ill people are regular people who make dinner and do laundry and have failed love affairs. They are simply human, fallible but not failed.

Hornbacher is her own case study. Madness ends with her return from a recent stint in the hospital:

Thats what madness looks like: a small woman in baggy red pajamas sitting on a

kitchen chair, her feet dangling above the ground, trying to figure out how to eat an

éclair while everyone she knows and loves watches her closely….

They will know I am well as soon as I laugh.

I always do.

This memoir is, in fact, full of laughter, it’s just in more exotic varieties than we’re used to. On the one hand, there is the hysterical, uncontrolled laughter of mania which, to hear Hornbacher tell it, can be a rapturous state. The language and memory centers of the brain go nuts when you hit mania, so youll see stuff like wild alliteration, manic joke-cracking.(Both of which are appealingly present in Madness.) You find yourself so clever. You have this extreme entertainment with your own brain. You are full of jokes and good humor and good will. You want to make everyone happy. Your own elation and your desire to express language meet up in wit.

There is also, throughout the book, Hornbacher’s genuine amusement at what she calls the absurdity of a life periodically upended by mental illness. The writer may owe her instinct for humor and her lack of sentimentality, in part, to her fathers family, in which madness was an accepted, almost a mundane part of life. Upon Hornbachers release from the ER, after she accidentally severed an artery during a dangerous bout of cutting, her grandfather greets her, So, have you got your head screwed on right yet? I ask whether readers ever object to her sometimes lighthearted treatment of the subject of mental illness. For example, at one point Madness features a helpful series of bullet points preceded by this playful introduction: Here, Hornbacher writes, is how you make absolutely sure that youll keep getting crazier by the day. Do people find this kind of humor inappropriate?

No, Hornbacher replies. What people have said is, ‘Thank God you can laughand thanks for making me laugh.’ Does it have to be death and darkness all the time? If it iswhy bother? It is simply too hard if you cant laugh.

In contrast to her tongue-in-cheek signposts to the darkest reaches of bipolar, Hornbacher includes an informative, straightforward appendix bulleting Bipolar Facts and a directory of further resources. I wonder whether this is part of a mission to educate her readers about bipolar disorder.

The mission was to tell a story that was common, and is common, she clarifies. Although Hornbacher stops short of calling her book social activism, she tells me that, in a way, it is activist. I have a desire for a greater understanding. Im not going around waving my banner, but this is what I can do. I can write a book.

Make no mistake: Hornbacher clearly states that writing is, for her, in no way a form of therapy. Madness, however, makes a case for the genre of memoir as more than personal history. In a very real sense, this book is never closed. How do we know who we are or what we can become? We tell ourselves stories, writes Hornbacher in an epilogue. I am writing my story as I go. I am inventing myself one moment, one experience, at a time. And this leads to the well-earned optimism of her conclusion: I can write my future.

About the author: Hannah Dentinger writes on art and literature. She is also a scholar of medieval Welsh literature.

About Marya Hornbacher: Marya Hornbacher is the author of the classic Wasted: A Memoir of Anorexia and Bulimia, the acclaimed novel The Center of Winter, and the newly released Madness: A Bipolar Life (Houghton Mifflin, April 2008). She publishes criticism, poetry, and essays in journals and magazines in several countries. She lectures widely on mental illness and writing, and is currently at work on a new novel and a collection of poetry.