Letter to a ‘Wary Feminist’

Ann Klefstad responds to Miranda Trimmier's recent essay on feminist art and its rhetorical and aesthetic extremes. Klefstad offers an accounting of her own ambivalence about the cultural foment of those times, when she herself came of age as an artist.

MIRANDA TRIMMIER’S ARTICLE “THE WARY FEMINIST” (posted in mid-December) concerned her experience in a discussion put together by mnartists.org and the Walker around the Lynn Hershman Leeson film !Women Art Revolution (!WAR); the documentary looks at the rise of feminist art in the ’60s and ’70s, a time when women self-consciously made art as women. This recent panel was composed of intelligent women artists and critics: Trimmier, as moderator, joined by Laurie Van Wieren, Camille Gage, Margaret Pezalla-Granlund, Paige Sweet, and Susannah Schouweiler.

While Miranda indicates in her essay she found the experience interesting, her piece also lays out some problems, with both the concept of the all-woman panel and the premises of the film itself. She writes:

“I have to start with this question, in part because I don’t know a better way to begin: When we talk about feminist art, where does uneasiness fit? And wariness or annoyance? Ambivalence and silence? I ask because I imagine there are other women like me, and I’d truly like for us to be more excited to join the conversation. “

Let’s pause here a moment, backtrack a little. For those coming late to this discussion, here’s a quote from a PR description of Hershman Leeson’s documentary:

“An entertaining and revelatory ‘secret history’ of Feminist Art, !Women Art Revolution deftly illuminates this under-explored movement through conversations, observations, archival footage and works of visionary artists, historians, curators and critics. Starting from its roots in 1960s antiwar and civil rights protests, the film details major developments in women’s art through the 1970s and explores how the tenacity and courage of these pioneering artists resulted in what is now widely regarded as the most significant art movement of the late 20th century.

For more than forty years, filmmaker Lynn Hershman Leeson (Teknolust, Strange Culture) has collected a plethora of interviews with her contemporaries — and shaped them into an intimate portrayal of their fight to break down barriers facing women both in the art world and society at large. With a rousing score by Sleater-Kinney’s Carrie Brownstein, !W.A.R. features Miranda July, The Guerilla Girls, Yvonne Rainer, Judy Chicago, Marina Abramovic, Yoko Ono, Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, B. Ruby Rich, Ingrid Sischy, Carolee Schneemann, Miriam Schapiro, Marcia Tucker and countless other groundbreaking figures.”

So, there’s a bit of context. If you’d like the see the film, it’s still showing at various venues around the country, and word is the documentary will be released on DVD next month by Zeitgeist Films. You can also watch a lot of raw interview footage and see many of the artists’ works online.

Now, back to what we were talking about. In her essay responding to the film and its discussion of women’s art, Miranda continues, reflecting specifically on body-centric feminist work, of the sort artist Judy Chicago made famous in the late ’70s:

“But I find this feminism — and the art it inspires — narrow and off-putting. It is too certain in its politics, too totalizing in its tone, too one-dimensional in its representation of women’s experiences. [Judy Chicago’s] The Dinner Party is exactly the sort of work that makes me wary of feminist art.”

Both Camille Gage and Margaret Pezalla-Granlund, who were on the panel with Miranda Trimmier and the other women, have also responded to the film on the Walker blogs. Both of them did so with stories less about art than about their lives and juggle involved in the making of it.

Here’s the gist:

Camille relates her mother’s odyssey in the late seventies, when she left her marriage, took the kids, and went back to art school — and then quit art school for the second time in exhaustion, unable to complete her education while working to support her kids without help.

Margaret went to CalArts in the ’90s and reflects on her experience of the weird double standard of life-and-art of the time, that is still likely prevalent: if a woman wanted to do art, by the ’90s this desire was credible, but she was expected to sacrifice everything to it — forgoing children or a spacious life or even cleanliness for her work; this is not an exaction that men really deal with the same way. For instance, Margaret is also the daughter-in-law of a revered Minnesota sculptor, Paul Granlund, and he managed to do art all his life while maintaining a family and a house, in what seems like a reasonably balanced life.

______________________________________________________

Merely counting grievances can’t come close to communicating the oppressive and pervasive sense at the time that being female was not to be fully human. Suffice it to say, it was another planet from the one we now live on.

______________________________________________________

I READ MIRANDA’S EARNEST, SMART, AND CONFLICTED REACTIONS to the film and the surrounding discussion of feminist art, and indeed I share many of them. I’ve always been a pretty self-consciously feminist practitioner of whatever, but only because it has been necessary to be so — more necessary than anyone of Miranda’s age can likely imagine. Even so, I’m also someone who was pretty queasy about works like The Dinner Party, and others like it that conflate women with women’s bodies. I understood the necessity, on some levels, of performing this part of the rhetoric, but I still remember being pretty damn saddened by the necessary presence of the pussy in the room. Miranda’s are questions I also had as a young artist: Can’t we just be human? When?

I was born in 1956 into a society whose sexism had, if anything, increased since my mother was a girl. My father wouldn’t let my mother get a driver’s license (and he was a loving husband who had great respect for my mother’s considerable intellect); I was barred from taking shop classes in junior high and high school. In the small town where I grew up, I saw women and girls routinely hit and abused by men. There were no jobs for which women could be hired, in my world, other than nursing, personal care, or secretarial work. I won’t belabor descriptions of those days, as merely counting grievances can’t come close to communicating the oppressive and pervasive sense at the time that being female was not to be fully human. Suffice it to say, it was another planet from the one we now live on.

Judy Chicago, born Judith Cohen, though about my age, had a different experience from mine in some ways because her parents were radicals. For them, fighting the status quo was normal, and she grew up with a sense that what was, was not unchangeable. Early in her career, before she named herself “Judy Chicago,” she resisted the polarization that radicalism calls for; in the late ’60s she made a point of not applying to be part of a “women’s art” show, stating that she wouldn’t be part of any exhibition that was called “women’s” or “California” or “Jewish,” saying that “when we all grow up, we won’t need those labels.” But her experience of the art world in those days eventually did radicalize her, and blatant rhetoric became the brick she needed to break the scene’s painted-over windows. But I submit that even the maker of The Dinner Party would rather not have been limited to making work so unambiguous.

I went to college in 1974 and graduated in 1978. During those years feminist art was at its most rhetorically charged and polarized. At the time, I mocked straight-up “blood and hair art,” as I called it then. I even made an over-the-top parodic version of it for my senior show, a huge, fired-clay relief composed of every feminist motif I could think of: the unglazed clay itself (the earth!), stamped out with my bare feet into a 5′ 2″x 10′ field (I was 5’2″ tall — the autobiographical component, based on the body of the artist!); it was printed with a huge radiating circle (the circle of the goddess opposing the patriarchal square!); fragmentary casts taken from my own naked body were worked into the violently graven circle. Then, I cut it in strips, fired it, and glued it with Bondo onto wooden panels that hinged together into a standing screen (domestic furniture, not prestige “sculpture”!). And then I went to the local slaughterhouse (I’d asked them to tell me when they would be slaughtering a dairy cow) and caught, in a gallon jar, the blood from the throat of the cow when they slit it; there was milk flowing from the cow’s udder when they cut her up the middle. I poured that blood into cafeteria bowls and set them as offerings along the base of the curved, embellished terracotta screen. I changed the blood every day from a jar I kept in a refrigerator in the gallery basement (it got pretty clotty and smelly).

The work was meant to be satire.

The thing is, I’m not proud of my attempt to be above all these self-consciously feminist concerns. I’m not proud that I tried to ingratiate myself with the (exclusively male) arbiters of the little art world I was in by mocking all these already confining feminist tropes. I was just so sure I didn’t need them, that I didn’t have to be part of all that brouhaha just because I was female.

______________________________________________________

As a young artist, I was pretty queasy about works like The Dinner Party that conflated women with women’s bodies. I understood the necessity of performing the rhetoric, but I still remember being pretty damn saddened by the necessary presence of the pussy in the room.

______________________________________________________

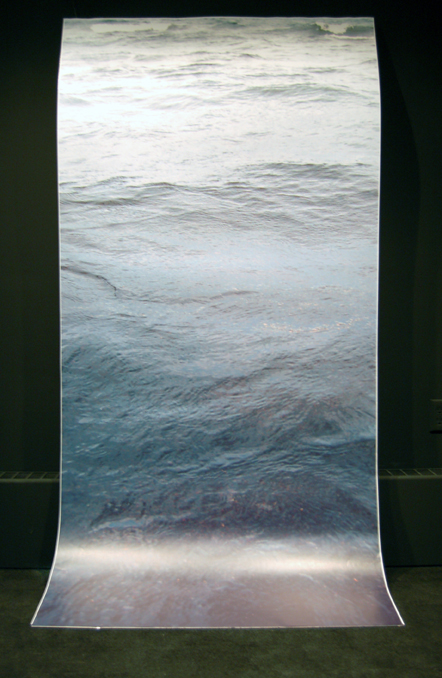

I made other works for that same show, more nuanced, and to my mind more interesting: translucent, brightly colored body casts made with waterclear polyester resin and fiberglass that hung in the light from the windows. I also made a 6′ x 6′ x 6′ cube of welded rebar, hung with black drapery and filled with rubberized string hanging from its ceiling; you could enter the cube and feel the soft strands on your skin. It had a soundtrack — a bit of soprano aria, played backwards in a loop on a reel-to-reel tape recorder, an alienized woman’s voice. My thesis paper focused on establishing the ontological grounds for a kind of sculpture that used all the senses: touch, hearing, scent, and taste, as well as sight.

And there was no reaction, in that time and place, to any of these works.

I mean, no reaction from my (mostly male) friends; no reaction from my professors. I was naïve about what to do next, so the next year I stuffed all that work into dumpsters and tried to forget about it. I went on to do completely private works on paper, things I could carry along on my nomadic life. And then I discovered Fluxus and the transforming power of simply being a catalyst in real time in the world.

I mention all this, because it is a familiar trajectory for women artists: first, they make themselves, because a female human being is something that must be created; the world denies you simple humanness. Next, they develop practices that are loyal to both their creativity and their need to sustain the life they have created (whether for themselves, or, literally, the life they have created: their children).

And heading back to the panelist’s responses to Hershman Leeson’s film — this is what both Camille Gage’s and Margaret Pezalla-Granlund’s responses to !WAR take up, in different ways. Both make the point that women who make art tend to be responsible, first, to the lives they create, and, next, to creations that engage in discourse with the art world; this may or may not be fair, but it can most certainly be excellent.

“Art” is not something that someone makes. It is something that one makes in a certain context of reception. (This is based on Arthur Danto’s notions of the cultural definition of art — to my mind the most realistic one on offer.) If the context can’t see you, can’t hear you, you simply don’t exist. Your work may be an artifact that you made, but it isn’t art. Somehow, the collective of other makers and thinkers and writers has to see your work as art — good or bad or awful or some damn thing –before it actually exists as such.

And this is something the women in the ’70s came to understand, from hard experience, when their nuanced, more ambiguous, not-so-obvious work simply turned into vapor and floated away in the obliviousness of that era’s art world. Those artists realized then that they actually had to create the ground for their own work, and the work of any other woman; they actually had to first make the dirt that they needed to stand on. So, they created unambiguous rhetoric, a kind of brick, and like Judy Chicago, they used that brick both to break windows and build the foundation for something new, and theirs.

These women didn’t need the art world to say that their work was good; they just needed the work to be seen in the context of the art world – to be something more substantial than transparent, to overcome nonexistence. In fact, they needed to get their work called awful, terrible, destructive, and obscene — because, after that, it’s a hell of a lot easier to get the more complex, more ambiguous work seen — at all.

So, well, yes — early feminist art work and art rhetoric can be seen as restrictive and confining. I know I saw it that way back in 1978. And the fact is, we no longer need to use the same cultural definitions and rhetorical extremes to valorize our gender’s marginalization. But the reason we don’t need to, is because those blood-and-hair-art women made the ground we stand on now; they spread the dirt. Like settlers on another planet, those artists created the atmosphere that allows us to breathe without thinking, to call out and be heard.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Ann Klefstad is an artist and writer in Duluth.

______________________________________________________