Le Rossmore est Mort: Vive le Rossmore!: Part 2

Here's the second part of the story of the Rossmore: what happens next.

The Unintended Consequences of Urban Renewal, or Out Go the Artists Who Saved this Building

ARTISTS ARE MOSTLY SHELL-SHOCKED AND DEMORALIZED about what is happening to the Rossmor, but they are not surprised, as it is a familiar story that has played out again and again across this ruthlessly money-hungry country of ours. In Soho and Tribeca, in West Hollywood, in Minneapolis’s warehouse district, and now in downtown Saint Paul, it is never the visionaries and creatives who save and restore downtrodden and ruined urban sections who reap the benefits of what they have sown. Instead, it is other, more predatory elements who eventually take the profits from the pioneers’ efforts.

“I don’t spite the guy who bought it,” photographer Larry Labonte says of the Rossmor Building. “Really it comes down to the cultural context in America. When cheap money is out there, people will grab it… As soon as the Rossmor was on the market, there was a huge demand for that space. As long as the culture is a grabbing one–there just won’t be many properties left [for artists].”

According to Antfarm, Inc.–the development company that has been charged with destroying the Rossmor as it is and replacing it with a block of 109 upscale condominium units–the Rossmor Building’s name and reputation was such that it was not difficult to sell to folks made dreamy-eyed by the chance to associate with the creative spirit of the place. As Antfarm’s website put it, we “created the entire marketing and advertising campaign based on the history, past and present, of the building.” Or, in other words, the developers were banking on the building’s association with artists and creativity even as they are destroying that creativity and turning artists out. (The ploy seemingly worked; as I was told several times by breathless agents, the units, priced from around $100,000 for the tiniest to nearly $300,000 for big corner spaces, all sold in less than ten days.)

“I feel horrible,” says painter David Rich about what’s happening at the Rossmor. “There are not a lot of buildings left that are affordable… It’s the issue of artists being real-estated out of their studios. We continue to go through it again and again. I find it is a matter of self-defense in the end.”

“This actually a huge inconvenience,” says public artist Cappy Glaser, who has held a studio in the building for the past eleven years. “It’s been a great break-up in a way. Some people aren’t going back into a studio. Larry Labonte put his stuff in storage… I’m disappointed. And I think a lot of people on the outside are disappointed. This was the best art building in Saint Paul. This was where the downtown art was.”

“Let me say this,” said Larry Labonte, “I’ve probably never been more depressed than in August when I had to hand in my notice. I had so many incredible memories. I was lucky to have a studio for 17 years. A lot of my life as an artist was made possible because I had such a cheap and reasonable place.”

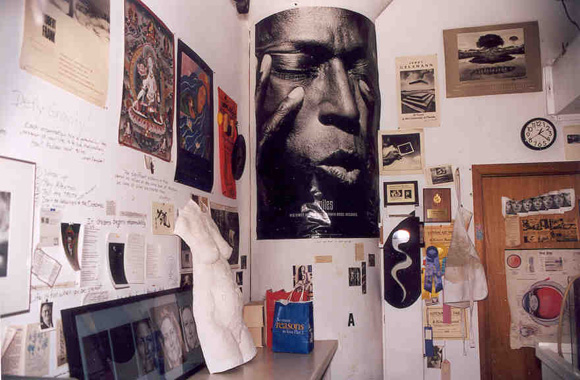

According to Labonte, the Rossmor was important particularly for nurturing some very important artists, each of whom came through and set up careers here–some before moving on to bigger and better things. Among the names he mentions are Wing Young Huie, Rebecca Pavlenko, Joe Geschick, Theresa Handy, Gaylord Schanilec, Perry Ingli, and many others.

Furthermore, according to Glaser, a number of artists ran businesses from the building as well–from individual artists, to greeting card companies, clothing companies, and so on. “I pay my bills with this work,” said Glaser of the work in her studio–mostly scenes constructed of various pieces of wood that are hung in public buildings. “I have to make money just like anybody… I think they should have paid businesses to help them move.”

When I visited this past November, the first five floors had already been cleared of studios, and construction had begun to transform the spaces into workable living units. A model unit on display showed what was in mind: a large open loft space with massive windows, polyurenthaned floors, exposed brick, an updated chrome kitchen off by the door, and a closet-like bathroom structure in the middle of the room. The model looked superficially like an upscale Soho studio-loft is supposed to look, but with a precious and lacquered-over quality. It was clear that this unit, priced on the higher end at $250,000, would likely never see a splotch of paint or the dust from a wood sculpture–no matter what the advertising says.

“I’m not convinced the Rossmor will be an art building,” says Glaser of the new model. “I don’t know how many artists will be owning here. I think the spaces are just loft spaces in general. I don’t know what the future of the Rossmor is as an art space.”

According to Larry Labonte, a lot of people are pretending that the arts are important to the new model of the Rossmor, and of the Saint Paul downtown. In fact, Labonte calls St. Paul’s, and current Mayor Kelly’s, commitment to artists “lip service.” “I suggested this past summer to a city development officer,” says Labonte, “that the city to establish a fund that artists could draw from to purchase their own spaces. The officer was interested, but there was not enough time to save the Rossmor.”

Labonte continues: “If the city was interested in a stable arts community, they’d be going after ways for artists to own their own places… They would have a stable community and a foothold in keeping downtown a vibrant situation they’re invested in… But this is what happens. Kelly says he wants to woo artists. Well, put your money where your mouth is. Why does it have to be about making money all the time?”

Despite the scarcity of studio spaces now, Cappy Glaser managed to find a new studio recently in the Jax building in Lowertown. Even before she moved in, however, she asked her new landlord when the building will be turned into condos. “He said, ‘Do you think I should do that?'” says Glaser, with a bit of dread in her voice. “I don’t want to move again.”

Cities go through cycles of boom and bust, and certainly seeing Saint Paul pull itself out from its long funk to recapture shades of its former grandeur is a good thing. If history is any judge, however, none of the resurgence of Saint Paul can be at all credited to the decisions of its often corrupt or inept officials; in fact, the opposite is true: as mentioned previously, their decisions exacerbated the decline of the city. To turn now against the very artists whose efforts helped bring about the city’s recovery seems like more of the same foolery. In fact, it is likely the death of the Rossmor is just the beginning of the end of a downtown Saint Paul arts community. It was reported to me that during the time the Saint Paul mayor’s office was attempting to force a downtown baseball stadium down the city’s collective throats a few years ago, a staffer of then mayor Coleman actually told denizens of a Lowertown artist cooperative that they had been targeted for extinction. This was despite numerous studies that show sports funding for downtowns is nothing more than a boondoggle that gives little back to the city or its tax base. (We don’t really need to read the studies about the arts as economic incubators and idea-generators; we’ve a perfect case study here in the history of the Rossmor.)

In 1850, at the New Year’s address, Father Galtier asked the town leaders that their community be renamed. With the approval of the people, he announced: “Pig’s Eye, converted thou shalt be, like Saul; Arise, and be, henceforth, Saint Paul!” Thus rechristened, Saint Paul grew into a shining city on the river bluffs. Today, according to city publicity, Saint Paul is again considered to be “coming of age, experiencing a refreshing renaissance that has changed people’s opinions.” As the material explains: “For the first time in almost two decades, new housing will reach downtown as the city hopes to attract middle class residents. For the first time, Saint Paul actually houses a major league sports team, the Minnesota Wild. The 2000 census posted a growth of 15,000 people for the city, the highest in 50 years. Crime is going down and property values are climbing up. Saint Paul is heading into the next century as a capital city with challenges to face but a stronger sense of hope than has had in a long time…”

It just looks like Saint Paul is going into the next century without the artists who kept hope alive for the city when the hour was darkest.

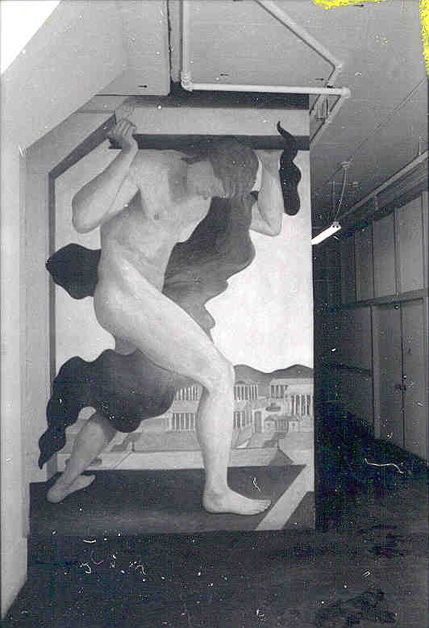

All photos courtesy Rebecca Pavlenko