Le Rossmor est morte; Vive le Rossmor! : Part 1

In a two-part piece (see below for part 2), Michael Fallon examines the role of artists in the renaissance of St. Paul, and the shabby returns the city has made them.

The Rise and Fall and Rise (?) of St. Paul

SAINT PAUL IS A CITY with a multiple-personality-disorder identity crisis. That is, on one hand Saint Paul is a place of stockyards, of mud flats and swamps and railway depots, of riverside breweries and hobo camps, of pig iron river barges and halfway houses. It is a pot-bellied and overalled burg of stevedores, bricklayers, blacksmiths, tanners, tinners, harnessmakers, saloonkeepers, and corrupt coppers kept on the payroll. This side of Saint Paul is all red brick warehouses, shoe and bullet factories, speakeasys and whiskey hovels, gangsters and river caves, lower landings, darkened pubs, river sludge and floods, and pig markets. In an earlier guise, this Saint Paul was once known, appropriately enough, as Pig’s Eye. It’s a place founded and built up by whiskey dealers, port keepers, fur traders, and hardworking denizens who’ve always scraped by nobly through the town’s ups and downs.

The other side of Saint Paul is the near-polar opposite. It is the metropolis of the well-to-do top hats of Summit Avenue. It is a map of neat elm-lined streets of brick and granite mansions. It is the city of summer sojourns to the North Shore, of tennis outfits, tea parties on the lawn, prep schools, and ivy-league bound up-and-comers. It is the golden dome of the state capitol, and the copper dome of the great cathedral. It is the locus of literary ambition, of August Wilson and F. Scott Fitzgerald and Garrison Keillor. It is a city split by a sparkling miraculous winding river spanned by five bridges. It is the town of the great European-style boathouse on Lake Como, and the Europeanesque town-square park that is ringed by the Landmark Center, the St. Paul Hotel, the Ordway Performing Arts Center, and early-century Public Library. It is the chosen home of carpetbagger opportunists like Norm Coleman, of great robber barons like James J. Hill, and of corrupt officials like police chief Dick O’Connor who granted safe harbor in the 1930s to gangsters like Ma Barker, Creepy Karpis, and Baby Face Nelson.

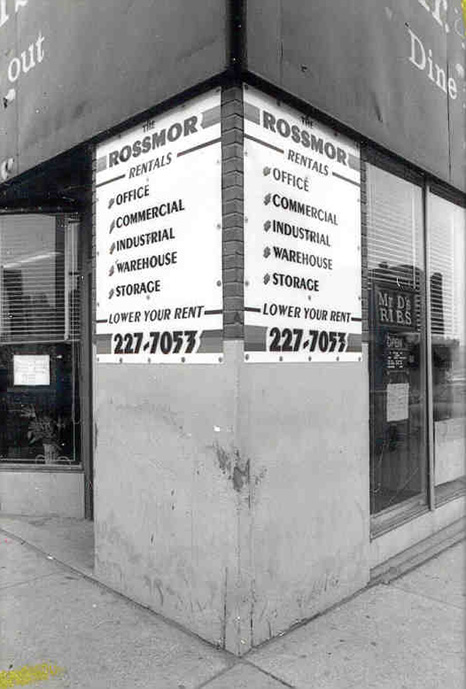

The history of this identity crisis goes back really only about seventy-five years. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, St. Paul, spurred by river trade and through its identity as a bastion of civilization on the edge of the frontier, was one of the fastest-growing and widest-open cities in America. Like other midwestern outposts of the time like Kansas City and Cincinnati, St. Paul’s character was initially full of promise and opportunity, and riches were deemed ripe of the taking. In retrospect, the reckless abandon that went into building such cities, and the freewheeling profit-taking was not sustainable. While most of mansions of Summit Avenue in St. Paul were completed during this era, as were the capitol building (1905), the cathedral (1915), and the great urban structures downtown-the Landmark building (1902), the Saint Paul Hotel (1910), the Federal Courthouse (1905)-this was pretty much as good as it ever got here. The Rossmor Building at 500 Robert Street, while not as great a structure as those listed above, but for our purposes an important building to mention, was built in 1916 as a shoe factory intended to produce refined product for the ritzy city’s downtown residents.

If this forty-odd-year stretch of time straddling the fin de siecle represents the ascendancy of St. Paul’s urbane and wealthy primary personality, the next seventy-five years are in many ways its attempt to regain its glory, no matter the costs. The Crash of 1929 hit St. Paul hard and quick, and changed the city’s personality. From optimism it moved to something darker and more cynical, as its citizens faced breadlines and uncertainty and terror from the gangs that took up virtual ownership of the city. Dick O’Connor’s unbelievable deal to grant gangsters safety as long as they didn’t endanger the city was flimsy, as the city suffered bank robberies, millionaire kidnappings, and bloody murders. An eventual crackdown by the FBI that brought many of these gangsters to trial in 1930s did little to change the city’s newly cynical outlook.

In the 1950s Saint Paul continued to flounder, mostly due to bad choices made by the city’s leadership. Downtown experienced widespread vacancies while the population of Saint Paul fled for the new suburbs. Well-meaning urban renewal campaigns in Saint Paul were damaging to the city’s spirit–destroying ethnic neighborhoods and ruining the diverse flavor of the city. Little Italy, the Italian neighborhood southwest of downtown, was judged a slum and leveled. The West Side Flats, a Latino neighborhood, was damaged by flooding and demolished. The neighborhood around the Capitol was destroyed, along with a line of neighborhoods through the center of the city (including the African American Rondo neighborhood), all to make room for the building of the I-94, the new interstate. The freeway that was considered an exciting new development actually led to increased urban flight and a diminished downtown street life. And even worse, old buildings downtown (including the New York Life Insurance Building and the Ryan Hotel) were destroyed and replaced by featureless and blank modern architecture. (One critic, for example, declared Saint Paul the “blank wall capital of the United States.”) The establishment of the skyway system even further damaged the city’s pedestrian soul.

The Rossmor Building in particular perfectly illustrates the descent of St. Paul from a pre-Depression Dr. Jekyl to its modern Mr. Hyde self. By mid-century, the shoe company, like many downtown businesses, had vanished, and the Rossmor was all but abandoned. Though the building’s location–just a few blocks from the capitol–was prime, looked at objectively the Rossmor was not worth noting. A roughly horseshoe-shaped, dirty-blond brick structure that takes up a half city block and rises seven stories over an inactive street of fairly nondescript businesses (the Trikkx nightclub, for example), it must have looked absolutely haggard and skeletal as an empty structure. But at that time many of the city’s buildings were abandoned, so the Rossmor’s decrepitude was nothing extraordinary.

In the 1960s, Saint Paul experienced even more terrible decay. Stretches of the city’s main commercial street, University Avenue, fell into ruins, and neighborhoods such as Selby-Dale, Frogtown, and North St. Paul were fast turning into slums. Even the formerly prosperous Summit Hill was falling apart, its great mansions descending to a state that Gatsby and his ilk would have thought impossible. In this atmosphere of deterioration, the seeds of hope sprang from unlikely places. Artists, accustomed as they are to bottom-feeding, discovered downtown St. Paul and moved in. Though the exact sequence of events are lost to memory, most artists that I talked to agree that the first artistic pioneers came to the Rossmor sometime in the 1960s. The artists were drawn by several factors: the large windows that made of any tiny studio prime; the cut-rate rents; and the fact that everyone ignored the fact that artists lived in these cheap studios.

According to several longtime scenesters, the Rossmor building gradually became the first artists’ studio complex in the all-but-empty downtown, and this helped pave the way for artists to occupy and resurrect other abandoned Saint Paul buildings–such as those now located in the warehouses of Lowertown. It is perhaps no exaggeration to say that the arts, and even more importantly the artists, kept alive Saint Paul’s formerly vibrant personality in its darkest hours, and preserved much of the city’s storied past by helping to preserve its buildings. That is, art became the last remnant of the civilizing influence that built Saint Paul.

By the time that St. Paul’s reversal was beginning in the second half of the 1980’s (the city recorded a small boost in population in the 1990 census), artists had occupied the Rossmor building and inhabited the downtown’s depressed streets for twenty years. David Rich, a painter with a studio in the building in late 1970s, says it was a lively place with an interesting mix of people, “all hours of day and night”– unusual for a downtown that was empty on evenings and weekends. In particular, he recalled the free-form conversations and exchange of ideas that occurred at the “slop sink” in the hallway–an urban think-tank that existed when most had abandoned the urban core.

Larry Labonte, a photographer who had a studio in the Rossmor for the past seventeen years says the space was “remarkable” for its creative energy. “I have fond memories,” he says of his time in the building. “The [Saint Paul] Art Crawl was started in the Rossmor.”

He mentions photos he took of the first such event, which occurred in the gallery that was formerly located in the downstairs of the Rossmor.

“It [the Rossmor] was a wonderful space,” Labonte continues. “Just the idea that you could open your door and to blow off steam you only had to go down the hall. The energy of realizing that so much artwork is being produced has its own effect. You would walk into the building and just know that people were making things.”

“You could always see lights on all over the building at night,” says public artist Cappy Glaser of the Rossmor’s role in the darkened downtown. “You could see people working on stuff here because the windows were so large. You could look up and know who was working. On the dock outside there were always people on nice nights. There was such a community feeling always at the building.”

In many ways, the Rossmor was the forerunner of a underground cultural renaissance that eventually counteracted the very decline of the above-ground city and helped lead Saint Paul back to its former vision of itself as a civilized city. The sort of exchange of ideas that occurred at the Rossmor for nearly forty years is among the advantages cited by social critics like Richard Florida, who touts the advantages of free-form downtown cultural creative activity. Among the institutions founded in St. Paul in the 1970s were several important theater groups–Penumbra Theater, Great American History Theater, Park Square Theater-as well as Garrison Keillor’s, “A Prairie Home Companion” radio show. The early 80s saw the redevelopment of Lowertown–including restoration of the Union Depot, the construction of Galtier Plaza, the establishment of the Lowertown Lofts, and in 1986, the awarding to Saint Paul of the “Livability Award” from the U.S. Conference of Mayors.

All of which makes that much more tragic the death of the incubator of this renewal. For as of December 31, 2003, the Rossmor Building is no more.

All photos courtesy Rebecca Pavlenko