Into the Heart of Darkness

Black steers all varieties of brightness into the shade, darkening and deepening lighter hues. Likewise, we can begin to see—through a glass darkly, so to speak—the random and formless as virtues. It is from this dark formlessness that Caroline Kent’s paintings emerge.

Darkness is our first reality, the looming riddle of our becoming. Throughout our lives—in the circadian rhythms of sleep and waking, in the creative imagination waiting for emergence out of the depths of the unconscious, in encountering the transpersonal at the horizon of consciousness—we repeatedly come out of the darkness and go back into the darkness. It is a fundamental part of existence. As the poet William Stafford made clear, “the darkness around us is deep.”

And yet we live in manic fear of it. The constantly illuminated din of 24-hour news and the blasting lights of cities that never sleep have warped our affinity for that darkness, giving way to false securities and misconceptions—as a society, we’re biased to believe that lightness is good and darkness is bad. We socialize these misplaced fears into race relations. Take a look at current events to see how forcefully this old misconception is still upheld. And let us be clear: in a racist society, and we most certainly live in one, we must keep distinct the epithets that arbitrarily color human beings and those cosmic forces that shape the soul. They are not one and the same.

Black steers all varieties of brightness into the shade, darkening and deepening lighter hues. Likewise, we can begin to see—through a glass darkly, so to speak—the random and formless as virtues. It is from this dark formlessness that Caroline Kent’s paintings emerge. It appears Kent spent the past several years engaging these elusive teachers; the exhibition press release for her new exhibition at Public Functionary indicates she returned to abstract painting only recently, in 2014, after a three-year hiatus. The 11 works that comprise this show, Joyful is the Dark, were all completed since then.

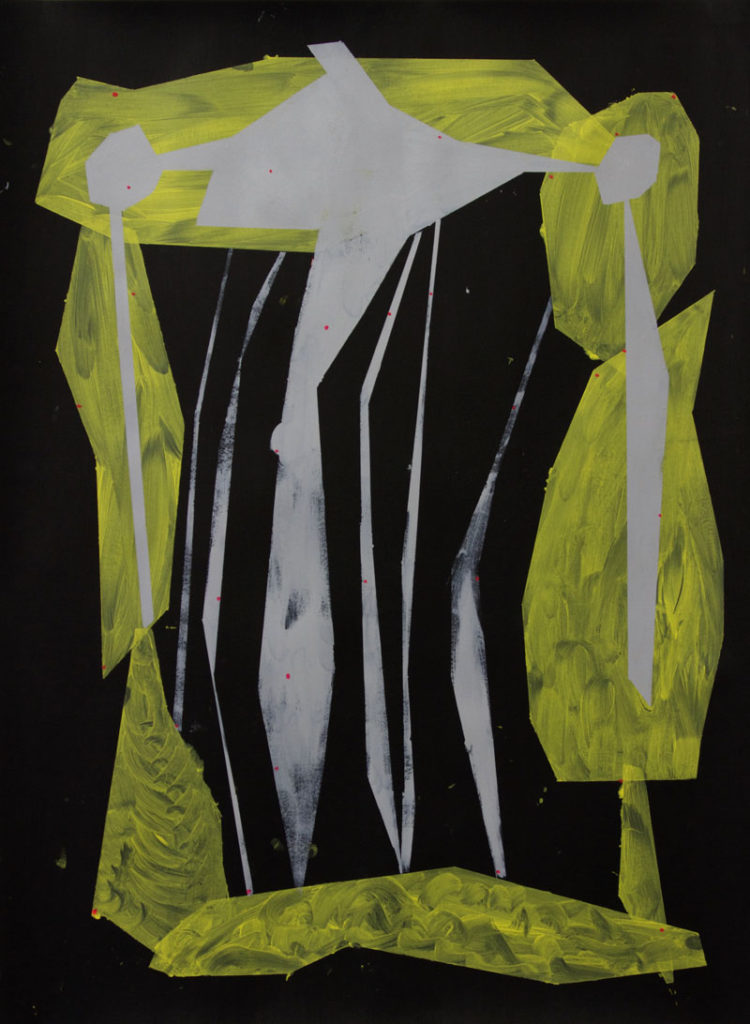

Kent’s recent work is dominated by a series of paintings composed on black paper, all measuring roughly 22-by-30 inches, five of which are included in this exhibition. (It is an engagement Kent continues beyond this show, and now totals over 80 works on paper.) These are truly absorbing paintings, mysterious and strange. For this exhibition the artist has displayed the five paintings on paper in eccentric, angled shadow-box frames. Each painting sits inside its structure naked and gleaming. There is no protective glass or barrier separating the work from the viewer. They call out in deep, resonant tones, beckoning us to come closer, like shadows ringing out from a dark bell. In Some have Shadows, Some have Walls (2016), a translucent yellow structure forms an open portal into the depths of the black ground. Out of these depths another form emerges, a shimmering, shadowy gray structure that floats onto the surface of the yellow, like a ghost covered in ash. Together the forms are spectral and waning. They stand as a reminder of unconscious complexes and vital energies undergoing processes of change, conflict, or integration.

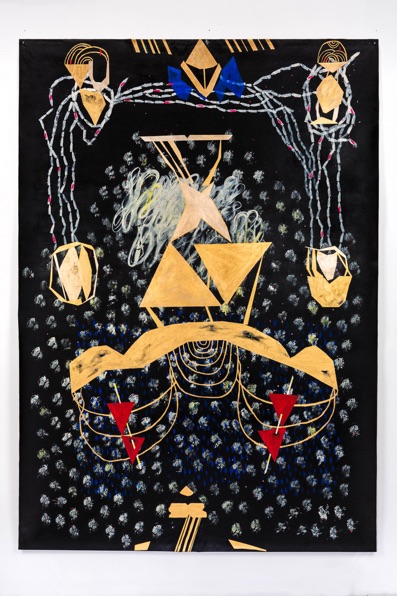

Caroline Kent, Further and Farther Than One Expects, acrylic on unstretched canvas, 2015.

Caroline Kent, Some Have Shadows, Some Have Walls, acrylic on paper, 2016.

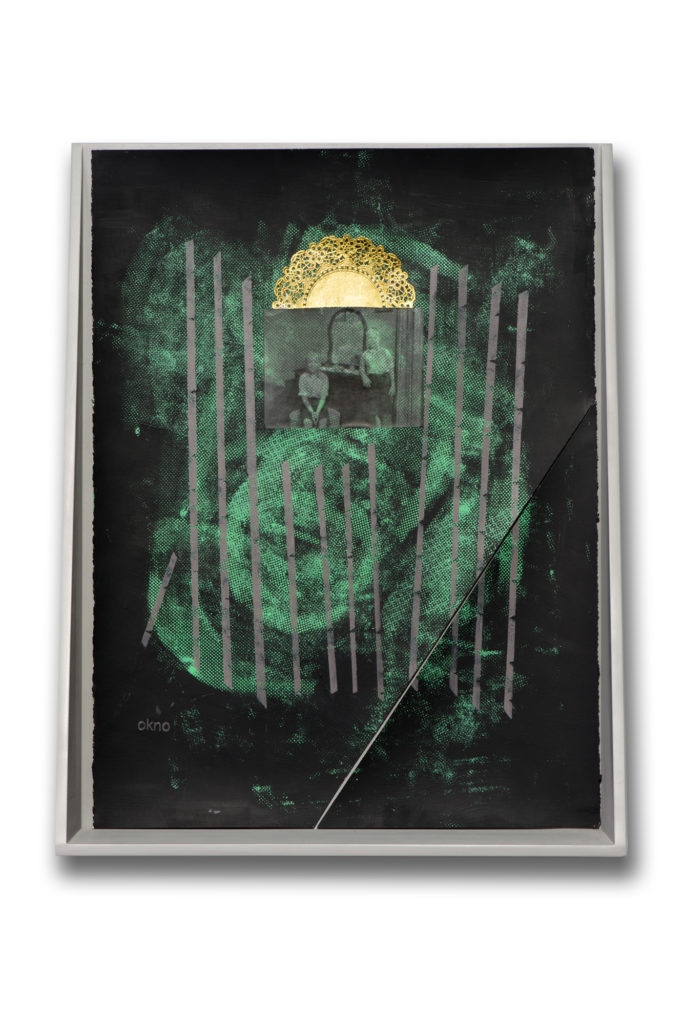

Caroline Kent, Twilight Zone pt.1/Okno, acrylic on paper. Photo: Rik Sferra

Caroline Kent, It’s Like Magic…, acrylic on unstretched canvas, 2015.

Each moment of darkening is a harbinger of alteration, of invisible discovery, and of dissolution of attachments to whatever has been taken as truth and reality. It’s the dissolving of dogmatic virtue. All certainties exposed in the internal light of the black flame appear now as strangers, paranoid tendrils identifying the depth of black’s radicality—a radicality that is not itself a paradigm, but a paradigm breaker. This moment of breakdown of identity is seen in Kent’s mixed media work on paper, The Twilight Zone pt. 1/Okno (2014). In it a spectral cloud of patterned glowing green emerges from the dark ground. It is trapped behind a structure of vertical gray bands or bars. Nestled within this barrier is the collaged image of two young boys; that image is positioned before a mirror sitting atop a dressing table. The boys look outward towards us, wearing matching white shirts and black bottoms; a gold doily seems to be emerging from, or setting into, the top of this image-within-an-image. It’s metallic surface shines with a golden, solar light. “Okno,” of the painting’s title, is the Russian word for window. We look through its invisible threshold to the mirror of our twinned soul, to the single-minded ego, split and mixed in the vagaries of twilight, reflected in the blank, blind eye of the mirror, blackened by the resonance of psychic potency. This psychological fissure is literalized in the work itself: the bottom left quarter of the paper has been severed and sits near its former self, separated from the main body of the work by a fraction of space.

Kent steps away from these darkened encounters, back into the accomplished light of reason, in the five paintings on unstretched canvas. Like the paintings on paper the canvases also have black grounds. They are large, handsome works, measuring around six-by-nine feet. These larger paintings feel more refined and studied than the works on paper. The press release defines the paper works as “studies in an effort to define a painting language.” As such, the works on paper are used here as a referent for the larger, apparently more fully realized paintings on canvas. Whereas the smaller paintings on paper feel immediate and vulnerable, emerging from a darkness that speaks of a reality outside human reason, the large canvases display the heroic struggle of intelligence over confusion, projection over reflection. The light of reason becomes stronger as our initial darkness begins to recede.

Approaching painting with reason and logic is an institutional strategy taught in MFA programs. With a reasoned approach one can, we are taught, come to a more intelligent product. Getting lost in the darkness and stumbling poetically with confusion until you reach an unknown end isn’t part of it. Creativity is a gift, not a strategy. This results oriented approach is highly valued in our society and espoused everywhere, from the reasoned projections of consumer habits by corporate interests to academic theory that claims to “shed light” on everything from Hawthorne to gender politics or the violence against non-white people. There is a problem (the darkness of confusion) that needs to be vanquished (by the light of knowing). But maybe the time is right to abandon the hero’s struggle, to step for a while back into reflective darkness, as Kent began to do in 2014 with her work on paper. It’s an obscure process, and one that isn’t always joyful.

The Torah says God set forth the rainbow as a visible sign that the cosmos is sustained by invisible principles. The rainbow doubly declares that the display of beauty goes hand in hand with discrimination, the spectrum of finely differentiated hues.

Related exhibition information: Caroline Kent: Joyful is the Dark is on view at Public Functionary in Minneapolis through July 23. See more of the artist’s work online here.