Locating the Original Royal Refugee

Mohamed Hersi on his battle with opioid addiction and how he forged practices in painting and clothing design

In an apartment in Hopkins, painter and clothing designer Mohamed Hersi, whose creative business is called Original Royal Refugee, carves out his work space in his home, finding time to work in between watching his kids and making trips to day care.

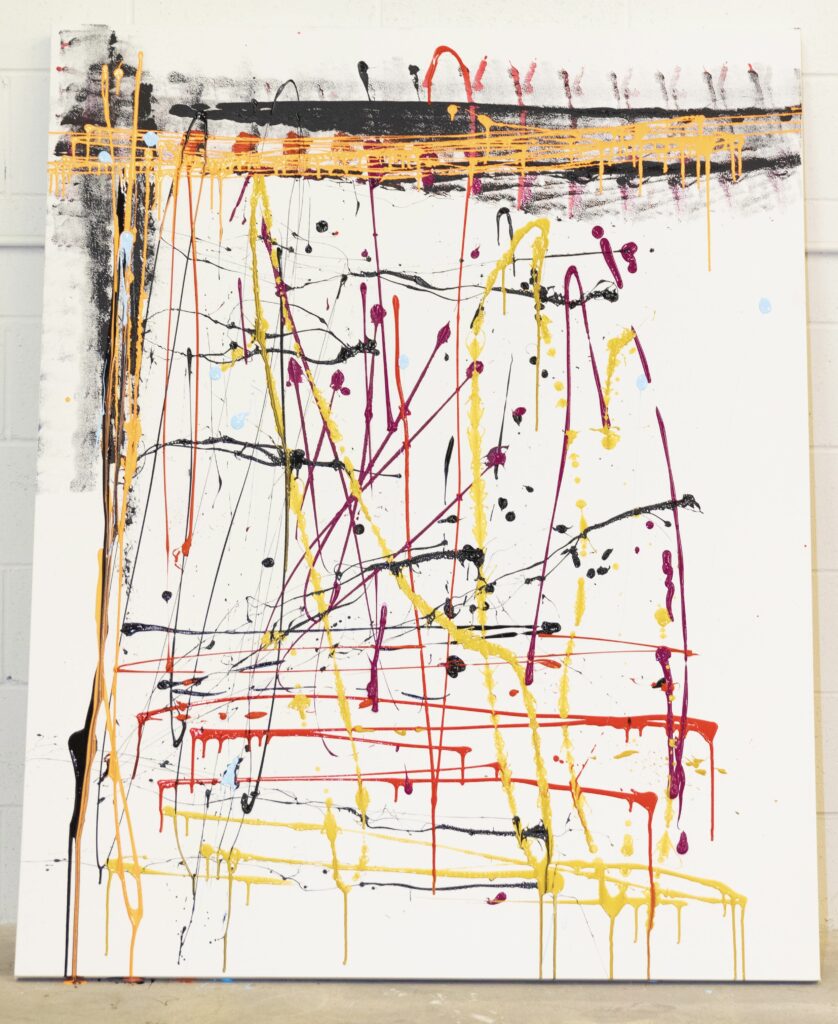

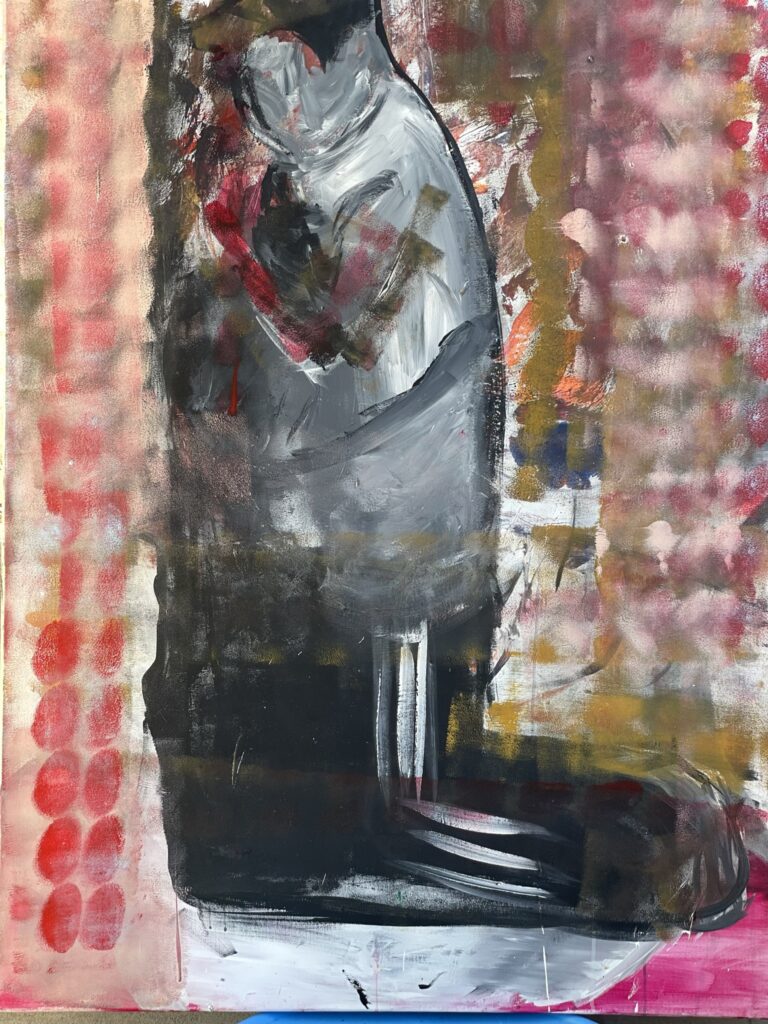

In one painting, bright trails of paint are spattered across the canvas in expressive, deliberate paths. He also has more figurative work that incorporates narrative into his style. Hersi hosts a gallery show of his work every year on October 10, and has also shown work with other arts groups, including Soomaal House of Art and City Wide Artists, and has a fashion business. Hersi, who went to hell and back through his addiction to opioids, takes things in stride, one day at a time.

Hersi attributes some of his creative flair to his mom, who runs a shop at Karmel Mall, known familiarly as the Somali Mall, in Minneapolis. Her background is in textiles, and Hersi has many memories working with curtains growing up at her shop.

Born in New Delhi, India, Hersi moved to the United States when he was nine years old. His mom was pregnant with him when she arrived in that country, which had no support system for refugees, and later moved to Australia only to find out they would not accept her children. Eventually, Hersi’s mother managed to move her family to the United States after a harrowing journey. “The stories that she tells of her crossing through these airports, it’s like a movie,” Hersi says. “It was very, very intense, but she is very brave. She is my biggest inspiration.”

Hersi was living in Hopkins in high school when he began making jean jackets as a creative outlet. He’d cut them up and experiment sewing them into new styles.

It was a natural progression, being around clothes all day at his mom’s store. “Everything around me at that time is clothing and selling and textile and fabrics,” Hersi recalls. “So that was kind of embedded within me.”

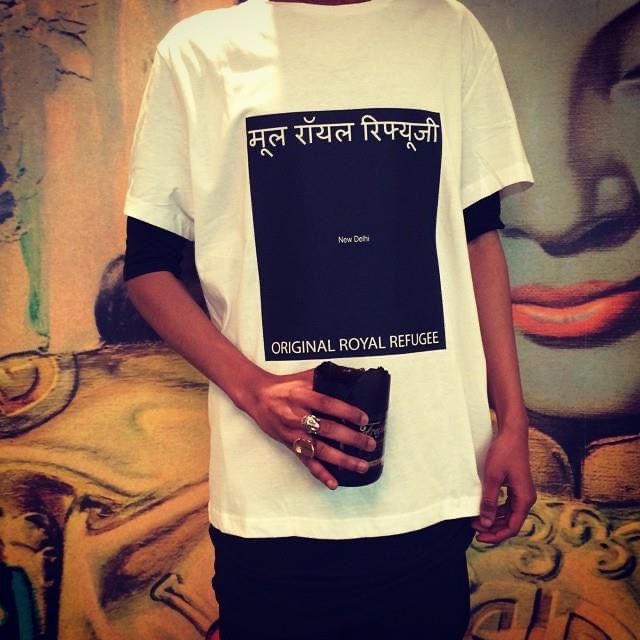

Original Royal Refugee, Bombay collection, 2016. Photo courtesy the artist.

Original Royal Refugee, Bombay collection, 2016. Photo courtesy the artist.

Original Royal Refugee, Bombay collection, 2016. Photo courtesy the artist.

After coming home from school, Hersi and his siblings would go to the store at Karmel Mall and sell clothes the whole day. “We would eat there,” he recalls. “We’d take naps there. Somali Mall is practically where we grew up.”

By the time he was a senior, Hersi’s whole life was clothes. “I loved fashion,” he says. He’d take jean jackets and paint flags over them. At his first concert, attending the artist The Weeknd, Hersi managed to get back stage, and had his picture taken with the artist holding the jacket.

For college, Hersi headed to MCTC (now Minneapolis College), where he found himself being drawn to the art section even though he wasn’t focused on art in his classes. “Whenever I finished whatever homework that I had, I’d run off to the art department,” he says.

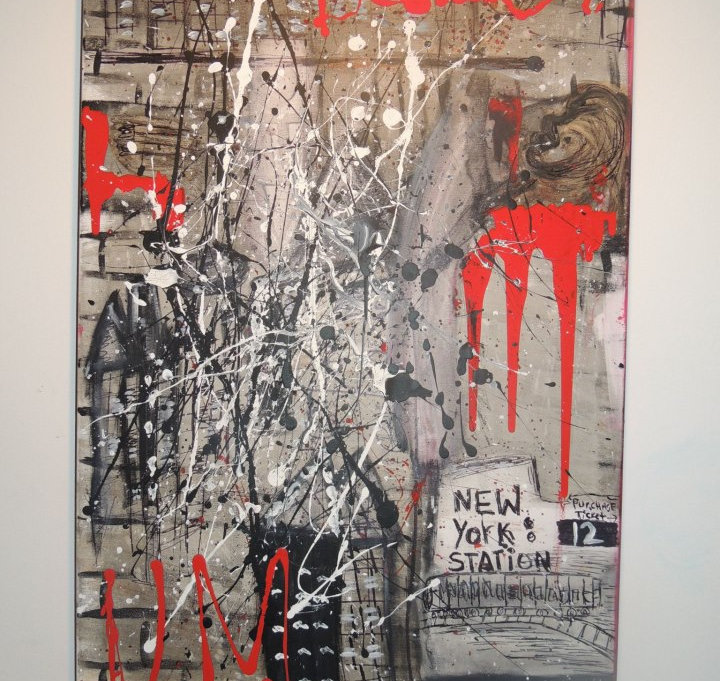

Hersi hosted his first art exhibition in 2013 at the Grain Belt Studio in Northeast Minneapolis. He promised the person renting him the studio space he’d give her a painting if he couldn’t come up with the rental fee.

The painting evoked a woman Hersi had known in New York when he was staying there. She took her own life, and the incident impacted Hersi enough to grapple with the experience using acrylic, oil, and pencil. In the top right corner of the painting, Hersi depicts the woman’s angst-ridden eyes, and at the bottom right corner, a subway station sign. The rest of the work houses vigorous paint splashes and textures to evoke chaos and despair, including bright red drips of blood.

“My favorite part was the background,” Hersi recalls. “I have tried to replicate it. I’ve never been able to redo it.”

He didn’t sell enough work at the opening to come up with the fee, and had to say goodbye to the painting.

Hersi’s current body of paintings address his struggle with addiction, which started after a knee surgery. Hersi went to a pain management clinic he had been referred to, which he now refers to as a “pill mill.”

“His business was about to go under and he needed people to come to his facility,” Hersi says. Initially wanting physical therapy, the doctor persuaded him to try opioids. Hersi threw up. The doctor told him to try again, this time not on an empty stomach.

“Since that day, you might have just thrown me in hell,” Hersi said. “Because that feeling good part that I got from my art and other things in life, he directed that to the pills.”

Eventually, Hersi got treatment at the Cushing Clinic, even though it scared him. “I was afraid I had lost my identity—the love that I had for painting—through the high.” It took him three years to draw himself out of the addiction and find a clean slate. He quit social media and focused on his work and his family.

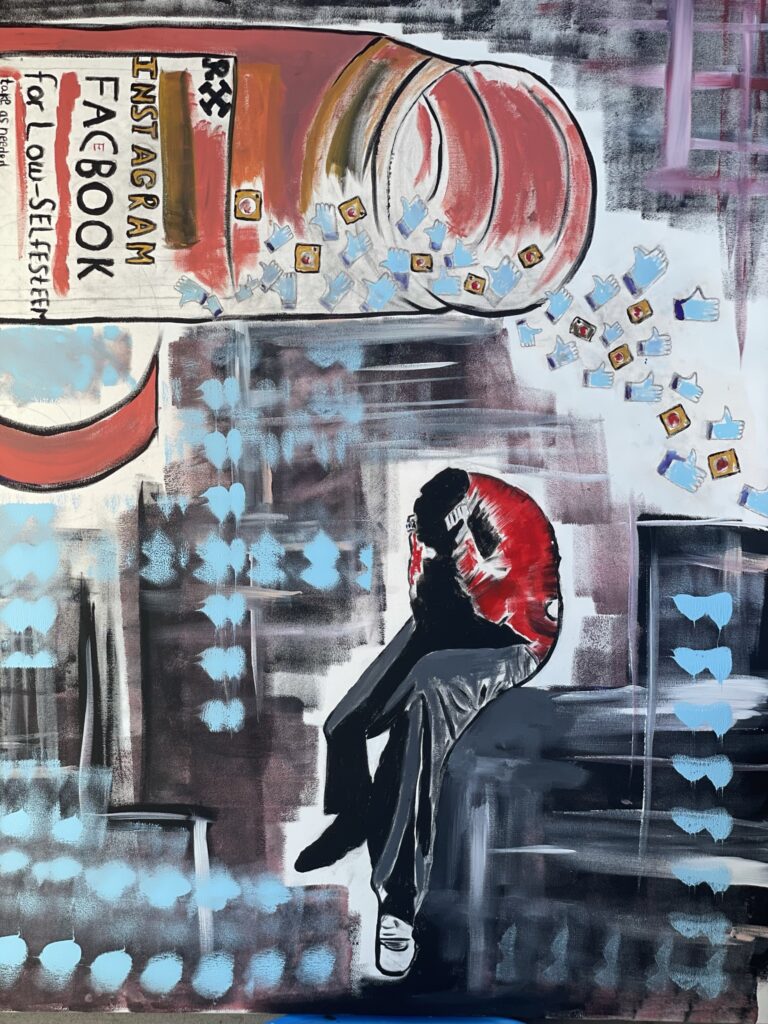

A painting he made during that time shows a man’s figure seeming to fall from the sky, clutching his head. The man almost seems to be headless, as a pill bottle that reads “Facebook for Low-Self Esteem” shoots out pills around him.

“I was using my paintings to buy my junk. I was supporting my habit,” Hersi remembers. “So while things were taking off, my addiction was taking off as well. Everything that I made, everything that was prized, or, you know, valued, would go towards the drugs after family and bills.” He says his desire to paint about his experience comes in part as a way to raise awareness in the Somali community.

Now sober for about four years, Hersi finds joy in creating balance, layers, and energy in his abstract works. “I can sit there and just wait. It takes a while to get it to the right color proportions.”

Hersi also finds himself wanting to address issues not only in his community, but worldwide. A recent painting portrays refugees escaping their home via a bright orange raft. A young boy looks on with curiosity at the arm of an adult perhaps struggling to survive.

“I want to give my paintings a meaning,” Hersi says.

Hersi made the painting around the time of his Syria clothing collection, all of which feature the Syrian flag. Hersi often finds his clothing design and painting mimic each other. His current clothing line, Moscow, like Syria, addresses a landmark where refugees are housed.

His line uses a lot of white to give off a wintery feel. “I’m focusing on refugees and immigrants that are in Moscow, reaching out to landmarks and places where other refugees are living there in the city,” Hersi says. His hoodies have numbers representing coordinates. “It’s a way of saying, “‘Hey, they are here in this country. We are here.’”