Sarah Sampedro: Interpersonal Spaces

A conversation with the 2021/22 MCAD–Jerome Fellow on her photographic practice that explores communities and belonging, the power dynamics of abstraction, and breaks down the forms of self and other

Melanie PankauYou describe yourself as a photographer who is interested in social systems, relationships, community, and belonging. Could you describe how these ideas unfold in your work?

Sarah SampedroI’ve always wanted to belong: to a specific community, a group of friends or family…I find meaning in being part of a larger whole. I want connection, so when I see disconnection, I want to understand why. This desire for belonging influences the ideas I pursue, and they often come from my relationships and life circumstances.

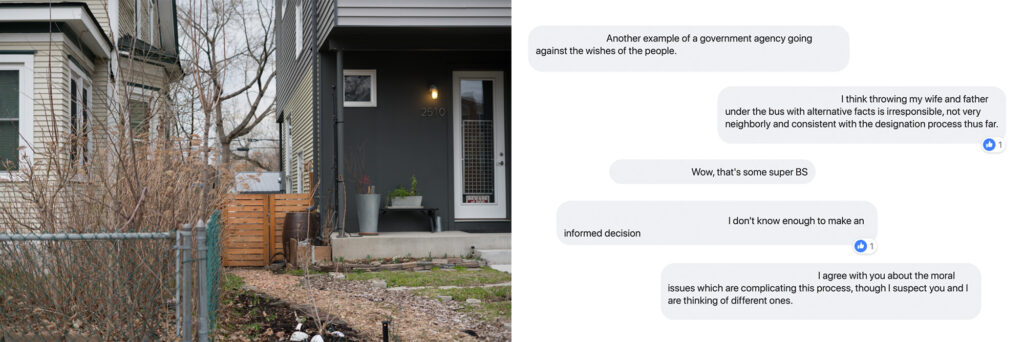

For example, past projects like Homewood and Covenant are about my neighborhood in Minneapolis. Homewood was a response to a neighborhood argument over a historic designation and gentrification, as well as an investigation into my role as a gentrifier. Covenant was an installation that grew out of the history of racially restrictive real estate covenants in my neighborhood. The first body of work investigated a contemporary disconnect in the community, and the latter investigated a historic cause of disconnect. I want to understand the history that brought us to where we are today.

MPI’m curious to know more about how you sequence images, particularly in your installation work. Could you walk us through your process of editing, ordering, and laying out a body of work in space?

ssFor me, sequencing in an installation is all about the relationship between concept and formal elements. The ideas need to make sense next to one another as well as across the room. What does the overall space say? What does this specific wall say? How is it in relationship to the wall across from it? Is a linear narrative important, or does the idea expand and contract throughout the space? In the same way, scale, color, line, shape, and other formal elements need to work together side by side, across the room, and in relationship with the size of walls and scale of space. It’s a classic example of form meets function. When both are equally strong, I feel it in my body.

MPYou mentioned you were working on a project about the 1862 Homestead Act and your family’s connection to it. Could you tell us more about this research and the images that are developing from this inquiry?

ssIn 1862, the Homestead Act paved the way for my German great-great-great-great grandfather to claim land. Not incidentally, the Homestead Act was signed into law the same year as the U.S.-Dakota War and forceful removal of Dakota people from Southern Minnesota. My research is centered around the history of this forceful removal of one group of people in favor of another, and my family’s participation in colonization. This work is an investigation into the history of my whiteness and the place I came from. I want to understand how I, and we, got to where we are now. I have many questions about land ownership, inequity, power, and control.

What does this look like in images? Sometimes it’s photographs of the landscape and sometimes it’s portraits; often the images include critique of capitalism or colonialism. But like all my work, the photographs move beyond documentation into an intangible realm of feeling. I am looking for visual ways to elicit a physical or emotional response, both from myself and the viewer. I want the images, ideas, and feelings to linger beyond the moment of engagement. Sometimes this power comes from a happy accident (like a timely cloud) and sometimes I happen upon something unexpected (like a caged bear in an old corn crib.)

MPYour photographs blend literal spaces with abstract images. Could you describe why you combine these seemingly disparate methods of image making? Alternatively, what kind of reading do you intend to elicit by pairing these images together?

SSPhotography can be a very concrete art form: it is rooted in “reality” and often understood as “truth.” For example, a picture of a landscape is understood to be a literal representation of that landscape. However, every photograph is mediated through the photographer’s perception, understanding, or intention. The photographer decides what to include or exclude, what idea they want to communicate, etc. A photograph made by a person is not objective truth. Documentary photography works very hard to be detached and observational, but the subject is always seen and portrayed through the photographer’s eye. A photograph is as much about the gaze of the photographer as the subject of the image.

In Waiting, Agency, and Power, I combined literal spaces with abstract images to disrupt the literal reading of the photographs. Instead of thinking, “Oh look, that’s a photo of a waiting room at a doctor’s office,” the addition of abstract imagery pushes the viewer to move beyond a concrete interpretation. Imagine sitting in a waiting room, bored, and letting your imagination wander. That’s the space I am creating. I also overlaid parts of images, or used formal elements to connect images across the wall. For example, a line in one image is continued in another. These interventions disrupt the ease of seeing or consuming the entire image, and play with the power dynamic implicit in layering.

MPAre there specific responses that you hope viewers will have after engaging with your work?

SSThe photographs I make are quiet moments intended to make space for thoughtfulness from the viewer. I want to offer ideas to percolate in one’s mind beyond the moment of engagement with the image. Our daily lives are often loud and busy, and I’m looking for alternative ways to be in the world. I want to create an idea, connection, or spark that lives longer than a brief encounter with my work.

MPWhat artists, writers, musicians, exhibitions, performances are inspiring you right now? And why?

SSA couple years ago, I saw Adrian Piper’s Probable Trust Registry and it remains one of the most influential artworks of my practice. In the installation, Piper invites participants to sign a series of contracts for ways to live in the world. At the end of the project, signees receive the names of every participant: a new network for intentional living. Piper explores trust, interpersonal relationships, and individual responsibility by activating a global network.

Nora Krug’s graphic novel, Belonging, is an examination of her German family’s involvement in the Holocaust and World War II. How do we reckon with actions of our ancestors? Of our country? Of our own complicity? I have many questions about this in my own work, and I think Krug digs into some of these questions with candor and vulnerability.

MPHow has winning the MCAD-Jerome fellowship affected how you approach your work?

SSI am both grateful and nervous. Winning this fellowship creates a deadline to complete work about an idea I’ve slowly been working through. I feel pressure to produce within a certain timeframe, but I also want to reject this feeling as pressure and embrace it as the gift of intention. With the exhibition deadline on the horizon, my thoughts always hover in the realm of my work, and it is a gift to live more deeply in this space. The threads of thought are tying and untying themselves, deciding how to weave together. It’s given me intention to reach out to curators with whom I’ve wanted to connect, dig into books I’ve wanted to read, and follow through with studio visits and conversations I’ve wanted to have. Most of all, this fellowship drives me to make this work as good as it deserves to be.

MPIf you could describe your work in one word, what would it be?

SSQuestions.

Sarah Sampedro is a Minneapolis-based photographer and educator. Her artwork examines the correlation between interpersonal space and social contracts as they relate to relationship, community, and belonging. Her art considers the histories, both personal and collective, that shape our perceptions of Self and Other, and the binary of “mine” and “yours.” Her work is an attempt to understand the psychological and constructed space that exists between all of us. Recent artwork themes include the 1862 Homestead Act, gentrification in her Minneapolis neighborhood, racially restrictive real estate contracts in Hennepin County, and the connection between power and agency. Sampedro was 2011/12 recipient of a MN State Arts Board Artist Initiative Grant, 2018 artist in residence at the Milchoff Atelier (Berlin, Germany), and 2019 recipient of the Picture Berlin Artist Residency (Berlin, Germany.) She also chaired the Minneapolis Art Commission and sat on the Minneapolis Public Arts Advisory Panel. Sampedro holds an MFA in Photography and Moving Images from the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities and teaches at the University of Minnesota and Century College.