In Living Color: Chris Monroe

Hannah Dentinger went to Chris Monroe's "Tee Shirt Show" at Starfire Screenprinting in Duluth and found a garden of edgy delight.

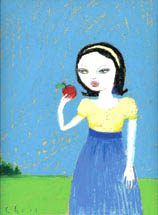

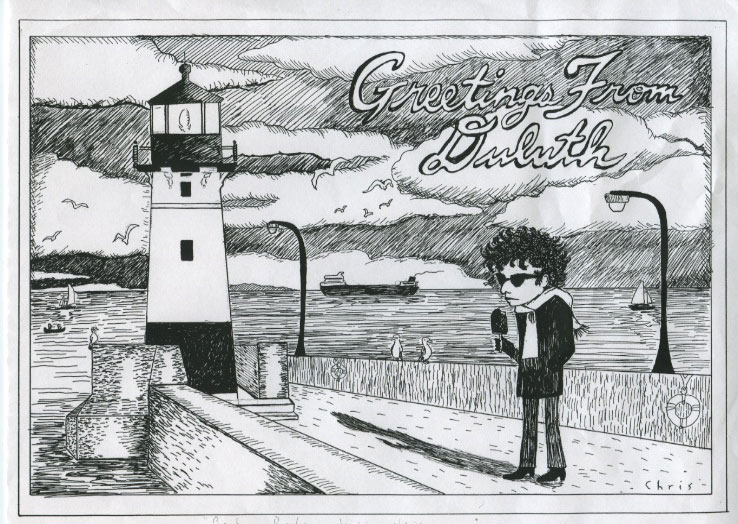

The indefatigable Chris Monroe continues to publish her “Violet Days” comic strip every week–this alongside designing logos (Will o’ the Wisp Books), album covers (Duluth Does Dylan), posters for special events (Duluth’s 2006 gay pride parade, for example), storefronts (Robin Goodfellow’s in downtown Duluth), and, of course, tee shirts.

There is a Chris Monroe tee for everyone, whether they favor her flattering portrayal of downtown Duluth’s notorious Cozy Bar, or perhaps the more salubrious Positively Third Street Bakery. A scruffy, 60s-era Bob Dylan is often to be seen stalking past these local landmarks, guitar case in hand.

It’s reassuring that everyone can have a piece of Chris Monroe, be it in tee shirt or comic strip form, because by the time I arrived at her show–only about fifteen minutes after it opened–nearly everything had been sold. “The T-Shirt Show” was the first art opening I have been to with commemorative merchandise for sale–a fittingly populist idea for a comics auteur. For the event, Monroe designed a tee shirt (what else?) featuring one of her distinctive skeletons: this one wears a top hat, clenches a cigarette holder in its teeth, and sports a tee shirt with its own image on it–which wears a tee shirt with its own image on it–and so on.

This neat visual joke is echoed in a picture of impossibly small mice gamboling on stalks of wheat that crisscross yellow against a bright blue sky. The mice resemble that most famous mouse, Mickey, who, indeed, appears on their tiny tee shirts.

Monroe quotes frequently from pop culture. The influence on her drawings of anime, a Japanese cartooning idiom, is visible in a number of the works on display. In “Hello,” for example, two figures float over a neon green lawn. One is a small, grinning purple bunny; the other, a sturdy-looking little girl wearing a Hello Kitty tee. She grips a tree branch in bloom in an amusing juxtaposition of Japanese-influenced imagery. The blossoming branch is a familiar feature of many Japanese woodblock prints and ink drawings as well as cropping up frequently in haiku. The Hello Kitty tee, on the other hand, is a product of Japan’s ebullient contemporary pop culture.

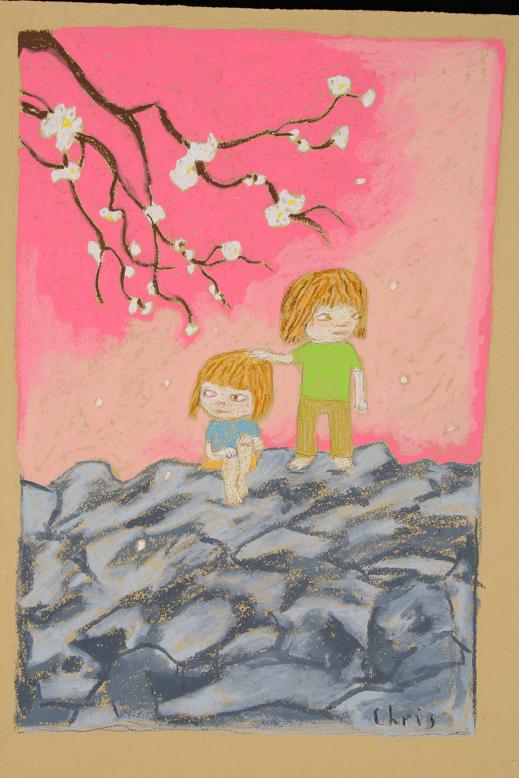

Another picture with a distinct Japanese air is “Cherry Blossoms.” In Japan, the blooming of the cherry trees is considered an important seasonal event. In this beautiful, unabashedly pink picture two barefoot girls are perched on rocks reminiscent of the churned-up shoreline of Lake Superior alongside Leif Ericson park in Duluth. The gnarled branch of a cherry tree bearing cottony white blossoms extends into the picture from the upper left corner. Fallen petals dot the air. The two girls could be twins, with their light brown bobs and almond-shaped eyes, but one is sitting and the other stands, her hand resting on the seated girl’s head in what feels like the gesture of an older sister. The two look in opposite directions but are linked by the action of stroking hair. The mysterious, almost Buddhist sense of peace in this picture differs from the lightly ironic humor that characterizes much of Monroe’s work.

“I Like Your Tee Shirt,” for example, is like a panel from a comic strip, speech bubbles and all. In the tradition of comics like The Far Side, it tells a story in a single scene. A girl with bright red hair who would not be out of place in a manga comic compliments a talking pig on his “I’m with stupid” tee shirt, apparently unaware that the arrow under the slogan is pointing at her.

The pieces were all done with oil pastels, a medium that allows Chris Monroe to exploit her fine draftsmanship with the added excitement of color. Her use of color is subtler than one might expect from an artist who works mainly in black-and-white, and unfortunately, that subtlety is lost in reproduction. You need to see the pictures in person in order to appreciate the blended shades with which Monroe conveys the contours of faces. Elsewhere, she creates texture by using her pastels so lightly that the grocery-bag brown of the paper shows through.

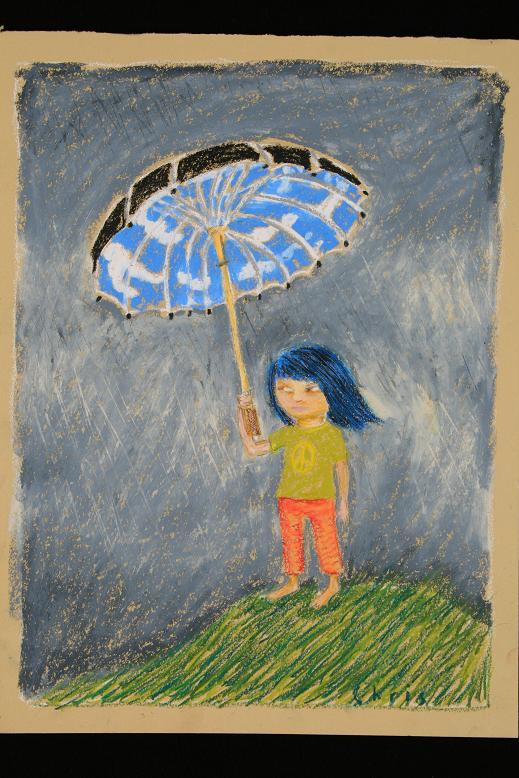

In “Peace,” a girl stands on a hill in a tee shirt with a peace sign on it. Her hair is particularly striking: Monroe layered black pastel over blue, scraping the black away to create glossy individual strands of hair. The girl shelters under an umbrella against a threatening sky. The underside of her umbrella is blue, patterned with fluffy white clouds. It is almost as though her optimistic thoughts have been projected onto it, while around her a storm rages. Taken with the symbol on her shirt which lends the picture its title, it is certainly possible to interpret this drawing in a political context. Monroe, however, has cautioned viewers against over-interpretation, telling the Duluth News-Tribune recently that she tries not to overload her pastel drawings with significance (Will Aschenmacher, “Colorful Horizons,” Duluth News-Tribune, September 27, 2007).

A figure with flyaway white hair (one exhibition-goer pointed out that it looks exactly like one of the Troll dolls that were so popular a decade or more ago) is dwarfed by a giant dandelion gone to seed in a surreal image called “Dandy.” The individual dandelion seeds with their feathery white parachutes were sketched using the same layering technique Monroe devised for “Peace:” a thick black layer of pastel is scraped away with a fine stylus to reveal white underneath.

The two figures in “Dandy” are positioned against a simple monochromatic background, as in many of Monroe’s pictures. There were two exceptions to this rule: “Papa Was a Rodeo” and “DS.” In the first, a slightly shifty-looking teenaged girl leans on a lawnmower, smoking. Among the features of the back yard in which she stands are a plaid lawn chair and a gas can. Perhaps it is the same teen who lounges on a bed in the latter picture, writing in her journal. Psychedelic patterns on her carpet, bedspread and throw pillows clash, suggesting a teenager’s passion for self-expression–but there is also a Sponge Bob toy on the beside table. The picture captures that uneasy stage between childhood and adulthood.

At first I was disappointed that so many of Monroe’s pictures had featureless backgrounds–I suppose I thought she ought to fill them up with ever-more-charming characters–but “Papa Was a Rodeo” and “DS” persuaded me otherwise. These have detailed backgrounds, and the detail tends to overwhelm the central character somewhat. The plainer the background, in fact, the stronger the impact of the main figure.

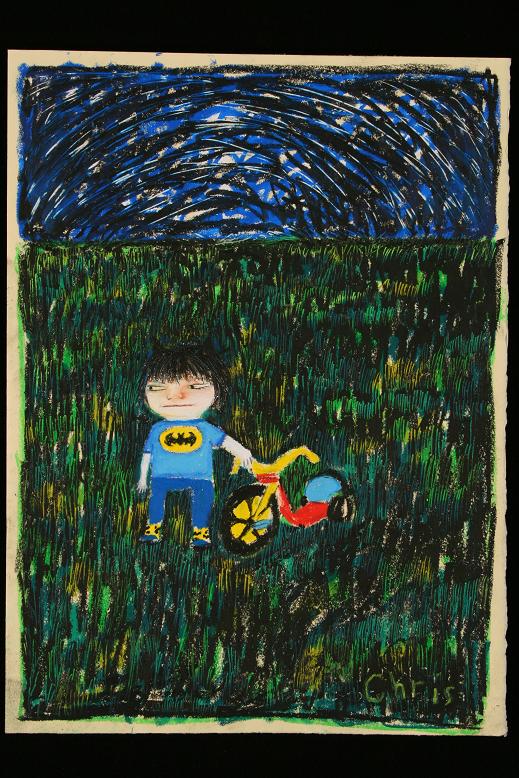

Nowhere is this better illustrated than in pictures called “Big Wheel” and “Finger Trap.” In the former, a black-haired boy in a Batman tee stands next to his colorful, plastic tricycle. He and his Big Wheel are the only brightly colored objects on a black-and-green lawn, under a black-and-blue sky. The boy looks a little lost, as though he stayed out past dinnertime and is waiting for his parents to call him inside. In “Finger Trap,” two friends have each stuck a finger in one end of what we used to call, very inaccurately I’m sure, a Chinese Finger Trap (the moniker must have come from the same source as “Chinese Jump Rope” and “Chinese Checkers”). The boys are absorbed with looks of delight in the ingenious toy: the harder you pull, the tighter the finger trap grips your digit.

Monroe’s lollipop-headed figures and her focus on childhood bring to mind that other Minnesota cartoonist, Charles Schultz. The wistfulness and whimsy that made “Peanuts” a more interesting comic strip than many are present in Chris Monroe’s work, but hers is smarter, wickeder, and funnier. Charlie Brown’s mistreatment at Lucy’s hands never varied, but in a recent “Violet Days” strip a kid is injured by a flamingo lawn ornament: Schultz never came up with anything like this.