Falling Together: The Life and Art of Russell Sharon

From a Minnesota dairy farm to the world and back—a life of seeking art, freedom, kindred spirits, and happy accidents

Born in central Minnesota, the artist Russell Sharon left the small dairy farm he grew up on at age 20 and went on to live an exciting creative life, living and working in Boston in the 70s, New York in the 80s, and Miami in the 90s. In his own words, he said, “I was there at the beginning of practically everything.”

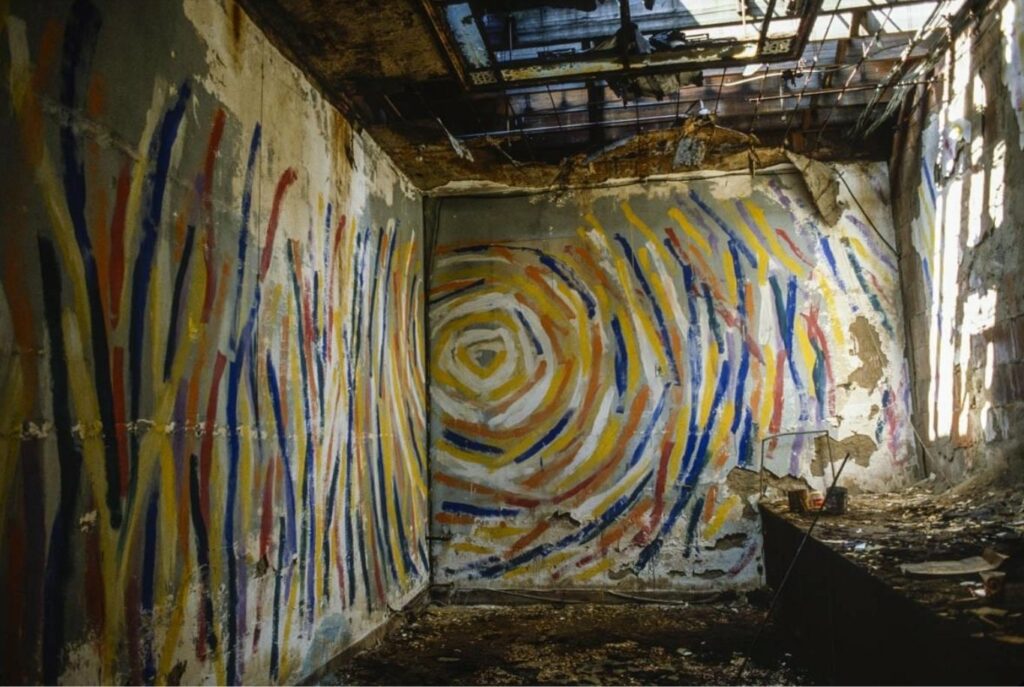

Sharon grew up reading obsessively alongside his farm chores, milking cows, and fixing machinery, starting with the texts his Norwegian pastor railed against: Voltaire, Dostoyevsky, and Nietzsche. He left Minnesota in 1968 to study in Mexico City, hoping to find kindred spirits—people like those he’d read about, who were loud, boisterous, and comfortable with moral ambiguity. In 1979, Sharon moved to the Lower East Side, and became active in the emerging East Village art scene, painting murals on the walls of the abandoned Pier 34 and participating in Hal Bromm Gallery’s 1984 group show, Climbing.

Sharon paints and sculpts, and moves between the two forms spontaneously. Despite working all over the world, his painting and sculpture have continued to take inspiration from the Minnesota landscape.

Russell is my godfather—a term that, in my family, bears little religious responsibility. Russell has, however, played a major role in my life in sharing with me his ideas about the artist’s life and its liberties. I recently picked Russell up and found him wearing neon green long underwear and his “Doctor Zhivago hat.” “People get so bored,” he said, lighting an American Spirit out the window of the passenger seat. “They need an artist, or a sort of clown, to keep them company.”

Like a sponge, Russell naturally makes connections between events he lived through and the big arc of humanity: he came out as gay in Mexico, shortly after the Stonewall Riots, his artistic career took off with the boom of the economy in the 80s. After losing many friends and two close romantic partners to AIDS, Russell survives HIV and lives back in the woods of central Minnesota, trying to use Siri and listening to Lex Fridman podcasts on the future of artificial intelligence. The following conversation is assembled from different interviews we’ve recorded over the past year, mostly at Russell’s home, a red farmhouse in a town called Randall. We sit in his studio, which is filled with sculptures made out of tree branches he’s turned upside down, and has a blue yoga ball hanging from the ceiling.

RUBY SUTTONOne of your first solo shows, at Hal Bromm, was the “chainsaw people.” Where did those come from?

Russell SharonI don’t know how. The idea popped into my head. It was the late 70s, early 80s, and Dutch elm disease was decimating every elm tree. I never think that anything horrible is going to happen. I’m usually very optimistic, but it was when the trees started dying—it made me feel so rotten. I was about 30. You could see the trees shrinking, turning yellow, because of this little beetle that would suck at their veins. I was visiting the farm when I saw it starting to happen. The first year 20 were dead. Then 30. Then they were all gone.

Those years really distressed me. We’d had about 50 elm trees, at least, on the farm growing up. Great big ones. It would take about three or four of us to wrap our arms around them. They were the most massive things in the county. A few years before Dutch elm disease started here, when I was your age, maybe 18 or 20, I planted a bunch of elm trees. I remember thinking, “Maybe I’ll live as long as these trees. That would be nice.” An elm tree with no disease would live to be about 100 years old. Later I wished I hadn’t thought I would live as long as those elm trees that I’d planted, because those were all dead and gone.

Anyway, when Dutch elm disease struck, there were all these beautiful logs. I guess I must have been looking at one of the spots where the elm trees used to be, looked at the stump and thought, “How can I carve it?” I used a chainsaw, because I knew how to use a chainsaw. I had a lot of fun with it. I made them into divers, people dancing. I couldn’t use any traditional tools, because that would’ve taken way too long. They had to be divers or jumpers, with their hands up, because of the shape. I wanted them to be life size. And orange, they were all orange—like a pumpkin, only brighter. I don’t particularly like orange. I guess I did one and it just worked, so I kept going with it. I guess I don’t like when things go to waste. I felt sort of sorry for these trees. They needed a memorial. It was a kind of apology from the human race, or recognition. Recognition that they had given so many people a lot of pleasure, and a lot of oxygen. It was a show of gratitude—as I’m hacking away at them, on the chainsaw. So my first show with wood was that. That set off a parade of wood work.

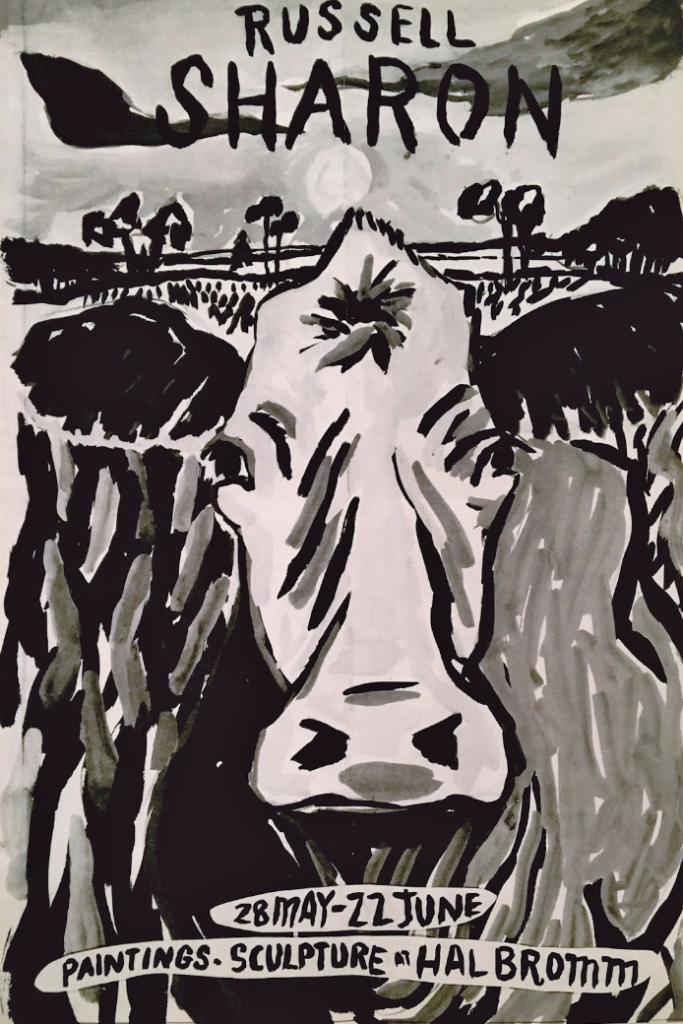

Russell Sharon, Chainsaw People, 1985. Courtesy Hal Bromm.

Poster design for 1985 Chainsaw People exhibition at Hal Bromm. Courtesy Russell Sharon.

Russell Sharon, Chainsaw People, 1985. Courtesy Hal Bromm.

RUBY SUTTONHow do you decide whether you feel like painting or sculpting?

RUSSELL SHARONYou know, in Florida, when I was there the last time, I sculpted. I’d never sculpted there before. But if I don’t sculpt, or do anything, I go berserk. And I wanted to make something for my friend from Switzerland. It gives me something to do, and it gives me a lot of pleasure. And while I’m doing it, it just flows. You can put green paint on a stocking, put some wire in it so it stands up straight. I might dip a little bit of glue around. I walk around with a blowtorch. It’s a good outlet for my energy.

I was introduced to painting by my sister Diane. She did it spontaneously. It was in her nature. She didn’t have to think, “Where am I going to put this line?” or, “What am I going to do here?” It just came out of her hands. I was so jealous. She was three years older. Then, in our little country school, we had art class, where we’d study drawing and coloring. The teachers, they didn’t know how to draw, but they suggested it was appropriate to stay inside the lines. I remember I always liked the way it looked when the crayon went outside the line. It made them look like they were alive and moving. But I couldn’t do that, or I would get docked. I would get an A minus.

RUBY SUTTONDo you think that’s why your paintings are abstract? Because, growing up, everything around you was so straight?

RUSSELL SHARONYeah, you know, when you’re living within limitations, unreasonable limitations, it’s annoying.

RUBY SUTTONHey, can I ask you a question? You taught me that people like it, when you prepare them for a personal question.

RUSSELL SHARONYes, people think it’s very polite when you ask for permission. It disarms you somehow.

RUBY SUTTONYou talk about how your family, and your mother especially, was always accepting of your eccentricities, because she understood that you were an artist, and that artists got to live by different rules. I was wondering if becoming an artist was a survival mechanism, in any way? To be free to be gay?

RUSSELL SHARONI thought of being an artist as a way to do what pleased me. But the problem with that was, I didn’t think of an artist as anyone that could make any money. So I thought for a while maybe architecture, because that interested me as well, and that would also get me away. But everything had to do, somewhere down there, with my need to get away. It wasn’t only a desire, it was a necessity. You know, when you’re getting to know people, you’re also getting to know yourself. If you don’t meet anybody, there’s no reflection—it’s like looking in the mirror.

And there was something sexy about art. Something magic. It wasn’t real, but it would come pouring out of my sister’s hands. Also reading, penmanship. These things you would write down and they would tell a story. I loved all that. I wanted to meet people who I could talk to and discuss Nietzsche with. Ideas. Philosophy. Or just possibilities: “What would you do if this happened?” Boys here would think I was crazy. I wanted to be able to be freaked out, and to freak people out. I also wanted to do drugs, and join a commune. And I wanted to join a family, a kindred family.

RUBY SUTTONAnd in New York, you had that.

RUSSELL SHARONThe stars were aligned for something. Once in a while, a major thing happens, because everything is making it happen. When I hit New York, it was like heaven for me. Previously I went to Switzerland. To me it was like a nightmare. I suddenly understood nihilism, and the desire to blow everything up, because you look around and there wasn’t a single thing you could improve. It drove me crazy. It was way too much control for me.

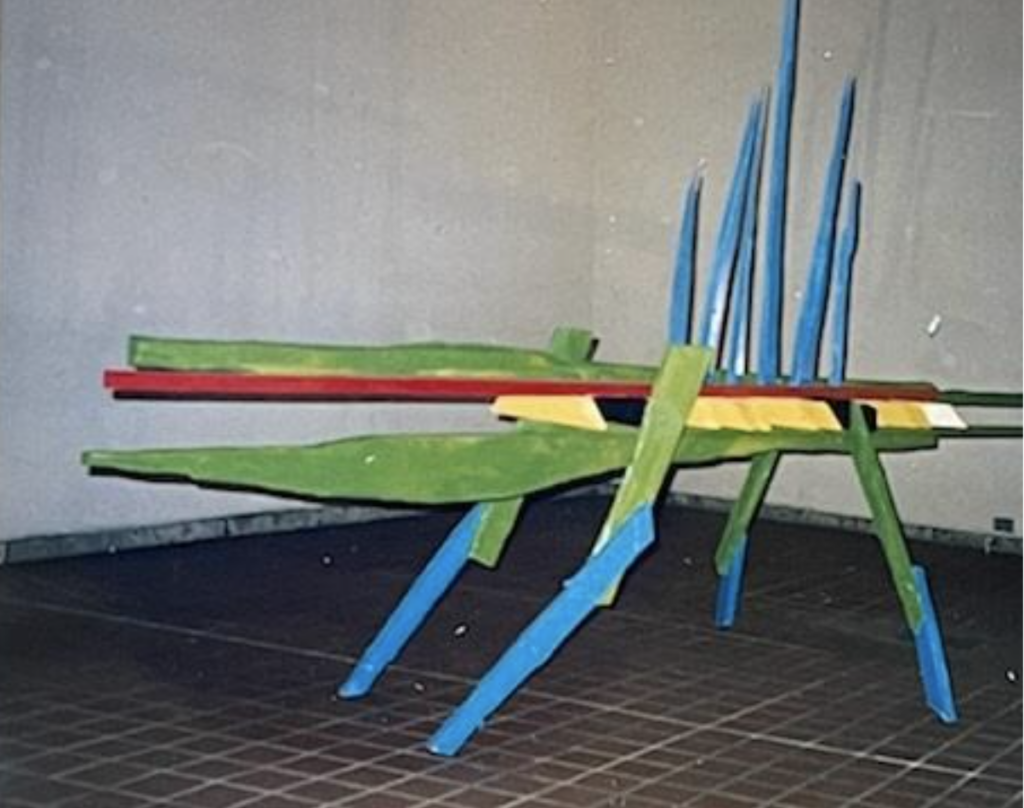

But in New York, you could look around and see a thousand things wrong. So you think, “I could do this, I could do this, I could do that.” That’s how we ended up doing those giant sculptures, in this vacant lot on 11th Street and Avenue A. You know, the East Village was totally dilapidated, it was full of garbage. People throwing away stuff. Did you see any pictures of those creatures I put up? All painted in bright colors?

Luis Frangella in Sculpture Garden, 11th St & Avenue A, c. 1986. Photo courtesy Russell Sharon.

Sculpture Garden, 11th St & Avenue A, c. 1986. Photo courtesy Russell Sharon.

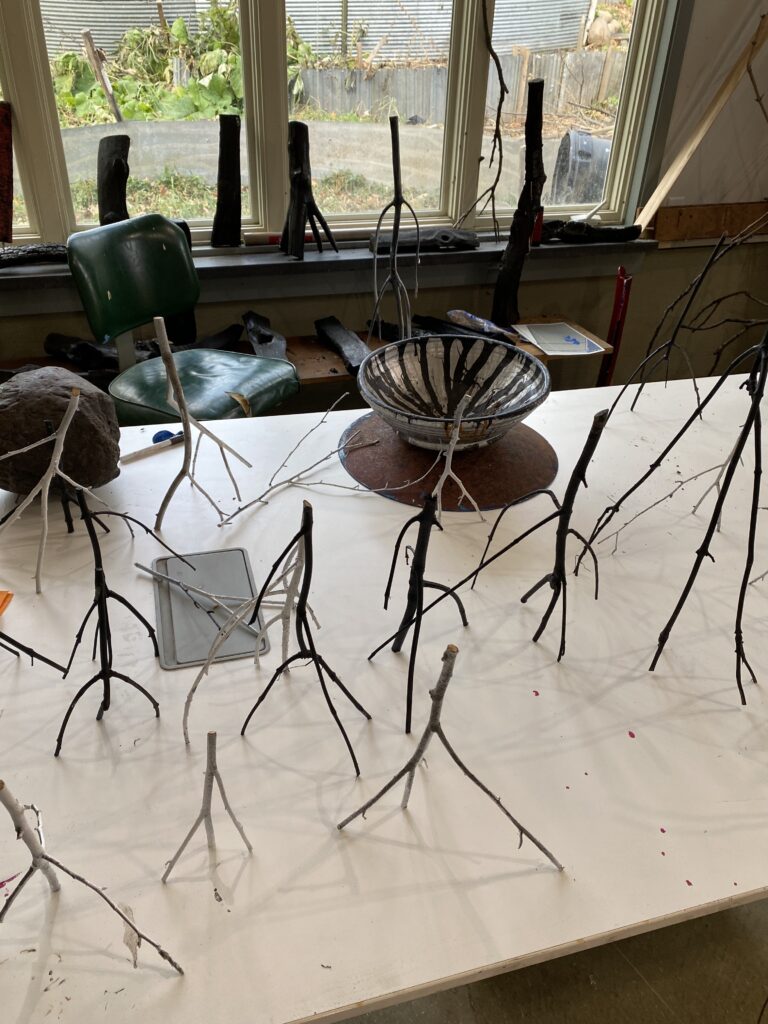

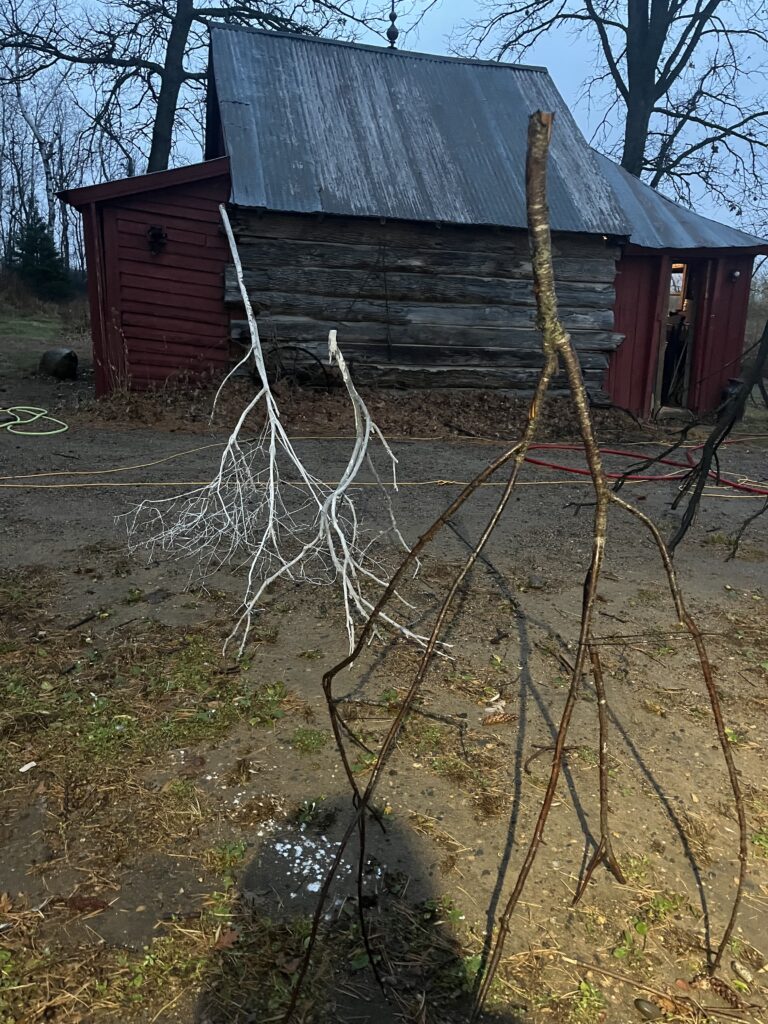

RUBY SUTTONIn your studio, you have a menagerie of tree branches that you’ve painted black and white and pink and red. Why are they called debutantes?

RUSSELL SHARONYou know, when you look at something—human beings, but probably chickens too—when you look at something that’s abstract, the brain tries to make sense of it by making something familiar out of the abstraction. I don’t like that this happens, but it happens. One day I was working in the garden and I started trimming the sumac bushes. That’s when I started seeing these different shapes in the sumac, which were so interesting. Something occurred to me, which was that if I were to turn it upside down, so the branches would go down, and the stem would go up, I could balance it. I brought four or five into the studio and started trimming them, because they needed editing. Just like writing. I go off on tangents, and they need to be trimmed, a little bit, or a lot, or entirely, to be read as something balanced and coherent.

When I had these branches balanced, so they could stand on their tips with the trunk up, my brain thought they looked like dancers. They were moving, sort of back and forth. They were dancers, even though they were not meant to be dancers, so I accepted that, because that’s the way it was.

Russell Sharon, Debutantes Ball, 2022.

Russell Sharon, Debutantes and Knee Nibblers, 2023. Photo courtesy the artist.

Russell Sharon, Debutantes, 2023.

Russell Sharon, Knee Knibblers, 2023.

Russell Sharon, Debutantes and Knee Nibblers, 2023. Photo courtesy the artist.

I decided to paint some of them black and some of them white, and suddenly they looked more formal. When people used to go to formal dances, the men would have the tuxedo on, and the women would wear white, a wedding dress, that sort of thing. So my brain went from there to thinking these looked like a debutante ball. I suppose ten thoughts popped into my head, and I chose debutantes. Because I thought it was amusing, or even funny. I really liked them. So I went around the woods here, and there were so many debutantes in the trees. And I rescued them. Now I have them in my studio, so it looks like one of those medieval dances. Someone came over one morning and asked me what I was doing last night, and I said, “I found a debutante in the woods and I dragged it in.” This made their head spin. They thought, “He’s getting crazier than he’s ever been.” That’s before I told anyone what I’d named them.

RUBY SUTTONI feel like the debutantes change your role, too, from being a force of nature to being more of an observer.

RUSSELL SHARONYou know, Duchamp started the idea of found art. He took things like urinals, or pieces of windows. He’d find them in the street, sign them, and suddenly, with his signature, it became art. It was a new idea. He has pieces at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; one of them is a broken frame of glass. The story was, he had found it somewhere and the museum was going to show it. The museum had someone assist him with the installation and the moving of this window, and the assistant broke it. The assistant was terrified, because he was a famous artist, and he thought he just wrecked his piece that was going into the museum. Duchamp looked at it and said, “Now it’s finished.” He said, “Now it’s perfect.” He was a little bit like John Cage, I guess, in this idea that spontaneous things that fell together could be art.

I know artists who admire Duchamp as having made some sort of breakthrough, where you don’t have to be in complete control. You have to give up control, sometimes, in order for a piece to grow in a natural sort of way. And if you have an accident, look at it very carefully, because maybe the accident is better than your preconceived idea. You watch very, very carefully. And before you get disappointed by, “Oh, I fucked up”—you think maybe you fucked up, but the accident didn’t. Maybe the accident actually corrected you and turned you in a different direction.

I think that my stuff has become found art, found objects. Only I find them in the country. Instead of a urinal, it will be something organic, something natural that grows. You look around and there’s something. That could easily be newly-discovered artwork from the woods. All it needs is a signature. Any artist could sign it, and it would be art. And how is it that one has the audacity to call oneself an artist? Do you know the answer to that? The artist is usually thought of someone who has some sort of insider magical powers, or that they’re sort of over the edge. Usually immoral on many different levels. They will go deep into the woods of the unknown and not pass preconceived moral judgements on this or that. You can see something through fresh eyes, without it being attached to any baggage. There’s been so much written about practically everything, there’s information about everything. But if you can drop all the definitions and just look at it… The more original it is, the less baggage there is, because fewer people will have time to criticize and sneer at it or praise it. I don’t think anyone has made anything like these debutantes I have found in the woods. I find that idea so funny. To find debutantes, who are so refined and elegant and trained to be perfect, in the woods here in central Minnesota, where you would expect to find Bigfoot, or a wolf, or a wolverine, or something.

RUBY SUTTONYour whole impulse growing up was to find a community of other artists. You had that in Miami and New York. And now you’re alone here. How does that work?

RUSSELL SHARONYou know, I was thinking of that yesterday. Years and years ago, when I was 20, I suppose, my whole idea was to go out into the world and do stuff, and then come back here, live here, and grow a garden and just be quiet in the country. So I got what I asked for. I’m not sure that it’s right, but it works. It allows me to be pretty much as crazy as I want. I like allowing myself to be eccentric. I do not like to be held in by fences or bounds or words. I guess I do go over the edge sometimes. People don’t have a clue why I make a joke. Very often I don’t, either. But when I was young, nature was my community. And now I have nature and a cat. So it’s doubled.