How To Be an Unknown Freelance Writer

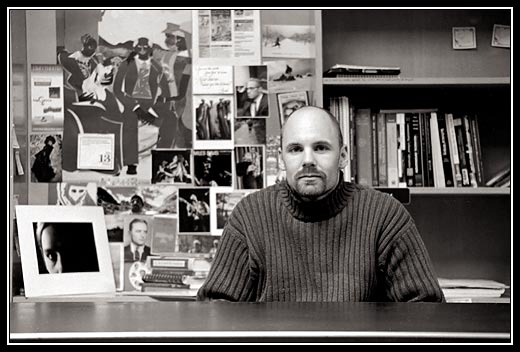

Chris Godsey tells you how to enter into the struggle to live by your wits and skill. The rest is up to you.

All writers, unless geniuses, have the same experience: years of painstaking effort; the gradual growth of facility, through endless practice day after day; the interminable disappointments; and the many false starts.

-Sigurd Olson

I’ve felt and thought like a writer, even been perceived as one by other people, since elementary school. It’s not that I’m a genius or even a little bit gifted—I wasn’t precocious and productive in my early youth, like Cameron Crowe, Harmony Korine, or Dave Eggers. It’s just that I’ve always spent a lot of time thinking in sentences and phrases; constantly casting and revising word combinations to express my perception of a particular situation, person, or feeling; seeking definitive details and the perfect words to illustrate them.

I’ve often been told that those mental tendencies come through in the way I talk—been told that I talk and “seem” like a writer. I also, till the last couple years, haven’t written all that much. I’ve written and published more than most people, but not nearly as much as I’ve felt obliged to, or as prominently as I’ve wanted to. Without external motivation, I tend toward intellectual catatonia. Here’s another way, from a more honest, narcissistic angle, to say that same thing: without a guaranteed audience or publication venue, I usually let laziness and the fear of being ignored keep me from creating.

Despite a constant urge toward the physical and mental tasks of writing—I have heroic typing daydreams, where I play my PowerBook keyboard like I’m the Thelonious Monk of typing, all rhythmic and smooth and insane, my voice a torrent of engaging, challenging conciseness and wit; I sometimes hand-write pointless lists simply to feel the connection between my hand and the friction of a good pen on paper—despite always thinking about writing, I’ve spent a lot of time in stupid idleness because fear and indecision stop me from starting.

I’m neither industrious nor blessed with foresight, which means I’m usually in a miserable mental cycle: miss an opportunity, lament the mistake, miss a few others because I’m looking back at what I didn’t do instead of ahead at what I might yet do. “If someone would just assign me something,” I often lament, about writing and other aspects of life, “I could do it. I don’t know how to figure it out. Damn those lucky bastards who actually know how to act on their creative impulses.”

Into the Fray

So it makes a lot of sense that after five stable, comfortable years of teaching college journalism and composition full time and writing on the side, I decided to chuck security and become a full-time freelance writer. It makes equal sense that while abruptly eliminating professional confidence, I also decided to leave Duluth, my womb for 15 years, and head to cold, cruel Minneapolis, a place that’s lousy with wanna-be writers.

Becoming a freelance writer was easy: I just quit teaching and started looking for writing work. That was two months ago. Being a freelancer—finding assignments, making money, avoiding insanity—is going to be a bit more difficult.

Since November, just after my wife, Shannon, and I decided to move so she could accept a new job, I’ve published three print articles, all in Minneapolis publications—two in the January edition of The Rake, and one in a February City Pages.

Since moving here just after Christmas, I’ve almost constantly begged editors around town to let me write for them. Some of my pitches have been really good. Some have been desperate and embarrassing. The Rake pieces came out two weeks before we got here, which means that since we’ve lived here I’ve been published in print exactly one time. I’ve also written a couple pieces for this site, which pays much less than The Rake (25 cents a word) or City Pages (20 cents), and contributed one story to the American Public Media radio show Weekend America ($325).

Two months: City Pages + Weekend America + mnartists.org = about 600 bucks. As a teacher I took home just over $600 a week, which didn’t, at that time, seem like much of a hole to fill. For a freelancer of my status, it is. It’s daunting and huge. Without Shannon’s corporate salary and benefits, I’d either be on the street, starving and in danger of ruinous medical mishap, or racking up enough credit card debt to ensure a miserable financial life well into our 50s (I’m 34, she’s 30).

Que Sera Sera

I expected every bit of the frustration and insolvency I’m struggling to transcend. I expected to be slighted—and somewhat justifiably–by editors who overlook my good sample writing because it bears an unknown byline and venue title. I anticipated wanting to give up when I realized that my competition is people who have written for Esquire, Spin, and many other prominent national publications. I knew there would be days when I’d court insane despondency by surfing the Web for opportunities, only to wind up confronting the overwhelming number of people who are already doing what I want to do, and who started doing it when I wish I had, and who apparently have the advantage of both natural and nurtured positive thought patterns.

I did not expect to develop muscular and almost serene self-assurance in the face of all that dark thought. I trust my voice, but I didn’t realize how strongly or sincerely I would come to believe that it’s powerful and unique, even among the deluge of well-written words I read every day. I didn’t know that my panic to publish now would partially be born of growing confidence and an aggressive desire to assert my voice—to show other people what thoughtful, tight, honest writing really looks and sounds like. That could be a classic delusion of grandeur; it could also mean I’m an accurate judge of my own skill and potential.

I’m not publishing with the frequency or prominence I want (or need, if I’m to pull my financial weight), but I know I will. I experience—and will keep experiencing, for quite a while–periods of crushing exasperation and self-doubt. But even those endless, emotionally eviscerating days are supported by an underpinning of faith in the inevitable result of patience and perserverance. No, it’s not faith. True faith is blind, ultimately unsupportable. What I have is empirical knowledge—valid expectations based in my skill, the illustrative careers of many other writers, and the natural order of the world—that as long as I’m busting my ass and handling my business, I’ll keep moving toward my objective.

The Three Cs

Based on my own skinny set of experiences, and on what I’ve observed about veteran freelancers’ careers, I’ve identified a few simple tools for building freelance writing success. They depend on each other, and they fall under three corny, alliterative categories: Contacts, Clips, and Confidence.

Contacts

•Whether it’s with editors, other writers, people who know editors and other writers, people who know the world about which you hope to write—whoever—intentionally meet and get to know people. Contacts (along with decent pitches and clips) got me my Rake and City Pages work, and the more those people get to know me and my ability, the more they’ll trust me, and the more credible I and my work will seem. Once I’m in the pipeline as a known, trusted entity, those contacts will lead to others.

Web sites like mediabistro.com and The Writer’s Market provide volumes of information about developing contacts, identifying niches and relevant venues, making successful pitches, and other important freelancers’ topics.

•Keep close contact with as many publications as possible. Read a lot. It’s been painfully frustrating for me to read stuff every day that I know I could have written, but the more familiar I am with what’s being published, the more likely I’ll be to submit unique pitches, and the more I learn about other writers’ voices, the more I’ll be able to identify strengths and weaknesses in my own. After digesting Minneapolis media for two months, I’ve learned that there’s a lot of good writing here, but nothing I can’t compete with. In fact, some of it’s not as good as it once would have seemed. I respect solid work, but familiarity has made me less likely to believe anyone’s hype, including my own.

•Get to know other writers. I hate hanging out with other writers—I’m not a joiner of groups, I’ve known too many pretentious jackasses who call themselves writers without deserving the title (which leaves me reluctant to claim it myself), and I’m annoyed by stereotypical writerly conversation (e.g.—“I had a wonderful journaling session last night.”)—but people who write inevitably need other people who write, for feedback, support, and connections.

Clips

•When you do publish, keep good track of your clips, even the ones you’re embarrassed by or disappointed with. Print or cut out paper copies and file them in a safe place. They’re tangible evidence for one editor that at least one other editor has trusted you and your work. A clip file can function like a network of human contacts: growth is gradual, prominence begets prominence, and subtle accumulation—of experience, contacts, examples–can have significant effects.

Confidence

•It’s often elusive, but if it disappears completely you’re done, because your competition won’t slow down and wait for you to catch up. Clinical depression and a learned talent for negative thought kept me from attempting to freelance for a long time. Now that I’m doing it, I’m often miserable with confusion and frustration. I’m also learning how to self-promote without shame or fallacy; I know that on days when I have no tangible assignment, I can still stay productive—take notes on possible topics, write and send pitches, walk around the Warehouse District and practice shooting photos, maybe write some spec stuff—in ways that will literally pay off when I create an opportunity or one falls in my lap.

For me, the best way to stave off insecurity is to stay busy. Walk to a coffee shop instead of sitting at my desk. Turn panic or indignity into motivation. Be diligent and organized and forward-thinking to a psychotic degree. The best way for me to wind up on the edge of tears, mentally depressed to the point of physical fatigue, is to sit inside, obsessively surf the Web, and deceive myself into feeling inferior to more-experienced writers who might never have been in my emotional state, but who certainly had to go through some version of the process I’ve only recently started.

To some people, I’ve always been a writer. To me, that’s a serious title, one not deserved by every person who attempts to arrange words in significant ways—the physical act of writing doesn’t guarantee status as a writer. At least not the kind I want to be. I’ll get there some time. I hope it’s soon. I’ll let you know when I arrive.