‘Here & After’ and ‘Slippery Fish’: the week in local dance

Lightsey Darst saw Time Track Productions' recent "Here and After," with choreography by Paula Mann, media by Steve Paul and original music by cellist Michelle Kinney. Also up: Penny Freeh's collaboration with composer Jocelyn Hagen, "Slippery Fish."

HERE & AFTER, A MEDITATION INSPIRED BY THE LIVES AND POSSIBLE AFTERLIVES of four pioneering women of the past century (Gertrude Stein, Mary Church Terrell, Djuna Barnes, and Lucy Farrow), finds Time Track Productions (Paula Mann and Steve Paul) in a quiet mood.

Steve Paul’s projections flicker across the walls and floor of the Tek Box Theater (instead of sitting on a front scrim, as they sometimes have in the past), backing the dance with their subtler motion. A field of hay, or needles, trickles as the dancers’ shadows cross it and Stein’s words and letters drop down (“Can you find me in a home?”). Paul aims for just-there effects: You gradually realize that one shadow on the floor is out of sync from the one moving dancer—a ghost dancer. And Paul’s light-world blends with Michelle Kinney’s atmospheric music, as when a roil of flame and smoke on the floor matches the smudge, smolder, and burn of Kinney’s cello.

Paula Mann, too, clears out space in her choreography, working with a vocabulary that seems, after the hour of the performance, entirely comprehensible. Gestures from women’s lives—washing, crying, clothing, unclothing, particularly a wrenching down-the-leg jag that might be zipping, unzipping, or tearing a run in one’s stocking—abstracted and exaggerated, carry expressive weight. This is unapologetically modern dance: a back arch is a moment of escape, a hurling arm a bid for release; and these gestures show up over and over, as Mann rings the changes on them. A sequence in which one dancer does everything she can with her hands grasping each other is typical: in keeping with her material, with the challenging lives of her inspirations, Mann’s anything but prodigal.

In this pared-down world, even small changes are visible. In what I read as the afterlife, four women stand by the sides of two fields of fabric, a shimmering veil overlaying a drop cloth. They fall to their knees and stretch under the veil, rolling in it; then, they repeat the same motion, but on top of the veil. The first looks transformative, the veil a chrysalis; in the second, they fail to transcend, and their writhing becomes the agony of frustration. Here & After, despite its title, is not ecstatic: Vision and release remain grounded in solid work. Even in the afterlife, these women are still moving towards change.

This spring, I saw Time Track’s O the Humanity and wrote a paragraph on it in a longer review. Paula Mann wrote back, which hardly anyone does, and then she and I carried on a conversation, which you can read in two installments, posted this week and next, on the mnartists.org blog; the first part of our exchange is here. In that conversation, we discussed, among other things, the lack of outlets for creators to think and talk about what they’ve done. So, with that in mind, I called Mann to ask her what she did in Here & After and what she thought of it.

“I feel really happy,” she said. “I never tried anything quite like this”—a work based in research but not literally representing anything on stage (with five performers, not four, the dancers are mostly not separate individuals). She made the work quickly (under the pressure of a grant deadline), which she says she found “freeing—to just get that out and stop thinking about it.”

The pared-down feel was deliberate—Mann uses the word “stripped”—and she and Paul took advantage of the Tek Box’s lighting capacity to create an environment that was “immersive without being too insane”. The movement, “based on emotional responses” and on the kinds of work women did in the period of her research, invests a lot in a little; describing the zippering motion, Mann said, “You could put so much energy into that really tiny point.”

And why this particular point in history? Mann finds the period she was studying (1880s-1930s, approximately) fascinating, as a “moment when things are just starting to come to life”—in feminism, in modernism, in modern dance. “I love that period of dance,” she says. Her work reflects a different technical background, but the same investment in motion as expression and catharsis.

I was curious whether she meant to go on in this direction, but Mann’s next idea is a solo “about the singularity.” More generally, she’s not interested in settling on a formula for style or content. “I don’t want any more superficiality. I want to get at something. I’d like to have some kind of thread and just keep pushing myself.”

One more note on Here & After, about the dancers. Mann rounded up a stellar cast: Angharad Davies, Heather Klopchin, Leslie O’Neill, Roxane Wallace, and Kayla Schiltgen. You rarely see such powerhouse dancers in a pick-up project, and it was a pleasure to see how clearly they rendered the dance, how confidently they took the stage. But even among them, my eye kept going to O’Neill, drawn by her subtle shadings, the feathering of her beginnings and endings, the sense of deliberate choice about her dance. Deep in a back bend, she suddenly flipped over and sprang onto all fours; but she finished the motion lightly, almost caressing the floor. Her version of the “zipper” motion was more of a cool measuring down her thigh, without losing the move’s sense of deep-grained hurt—in fact, the hurt was even more palpable for her disciplined detachment. When O’Neill left the stage before the afterlife began — her “death”—her eyes, her expression, her motions, all seemed driven by present necessity rather than by choreography. Right now, this woman’s dance imagination is on fire.

*****

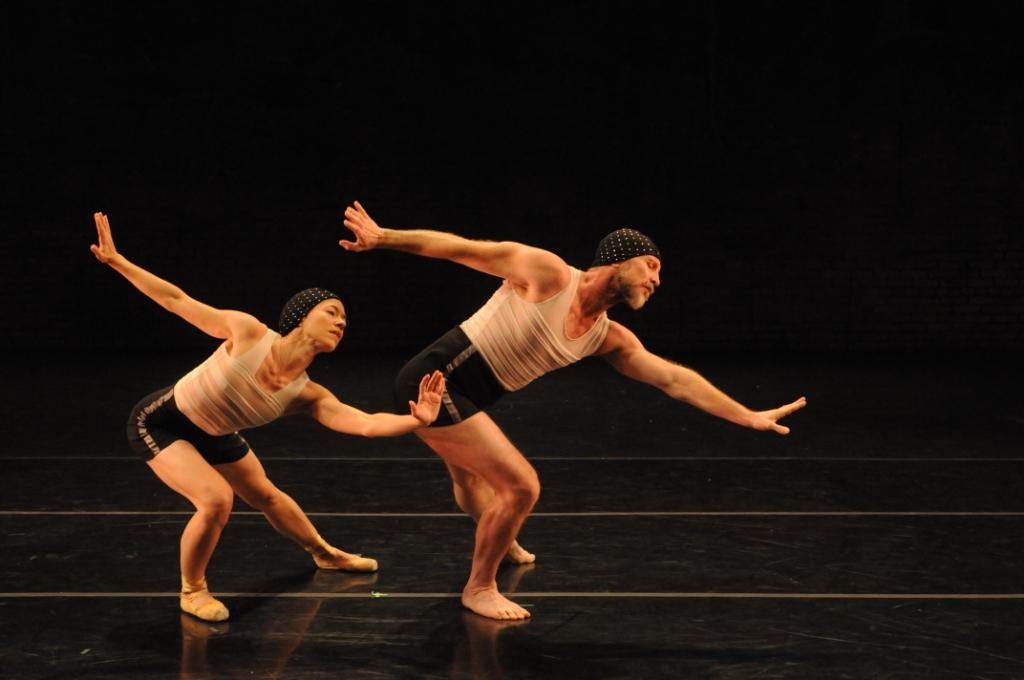

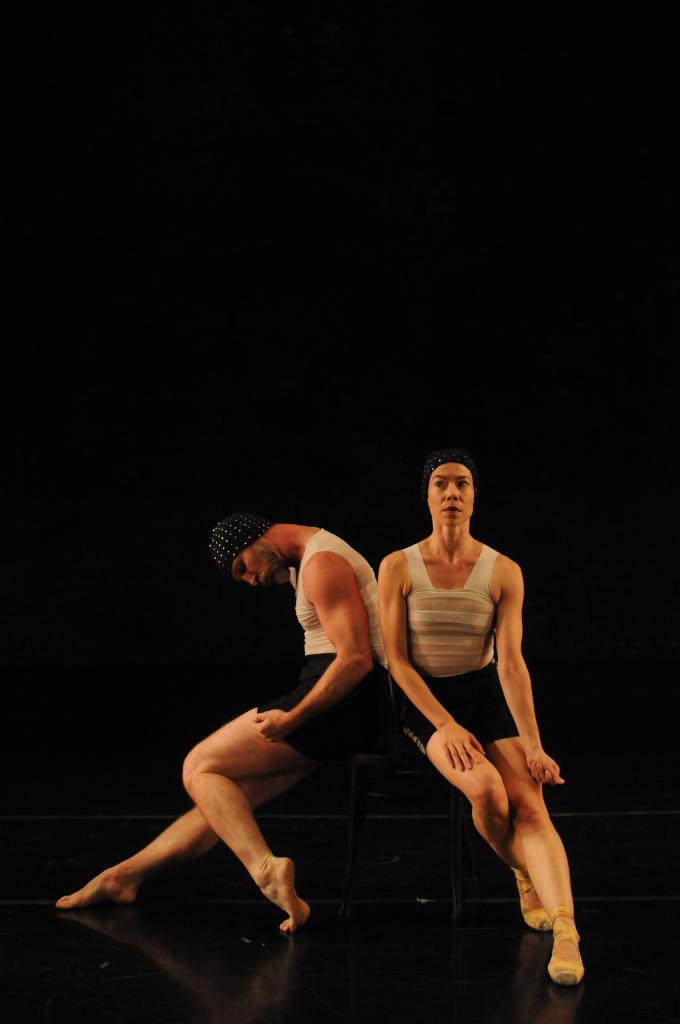

Another show from this weekend: Penelope Freeh and Jocelyn Hagen’s Slippery Fish. The ballet choreographer and composer shared an evening at the Southern, but I could only attend a showing of the half-hour title dance: a quartet with two dancers (Freeh and the excellent Patrick Corbin) and two musicians (violist Sam Bergman and soprano Carrie Henneman Shaw). All four performed together, the musicians moving, sometimes lifting or being lifted, and the dancers making sound — in my favorite moment, the dancer Corbin, his eyes closed, joined in a flight of percussion that began with his feet and pattered up his body to a soft hollow grasp in air. Garbed in tailored trunks, tanks, and a spangled swim cap for Freeh (the whole, the creation of Tulle & Dye, reminiscent of a 1920s bathing costume), the dancers seemed not quite conscious of the musicians, who moved around them, watching them, calling to them with Hagen’s music—soulful plucks, sighings, and a shivery groan-singing, never quite words.

I read them as past and present: the present inchoate, longing to speak to the past, which remains strictly etched, strange, sometimes wrenched (in Freeh’s angular steps). The lights go down over the dancers moving from one pose to another, as if we’re flipping through a stack of old photos: vaudevillians showing their tricks, a demimondaine and her man sucking on smokes, repressed respectability in a tightly set mouth. They look like dangerous people to be from—but then who isn’t?

______________________________________________________

Noted performances and related links:

Here and After by Time Track Productions (choreographer Paula Mann and media imagery by Steve Paul) with composer Michelle Kinney, took place at the JSB Tek Box in Minneapolis September 27 – 30.

Slippery Fish, and other offerings of new music and dance, by choreographer Penelope Freeh and composer Jocelyn Hagen was at the Southern Theater, September 28 – 30.

Read the first installment of a fascinating two-part exchange between Lightsey and choreographer Paula Mann from early last year, in response to her review of Time Track’s 2012 work, Far Afield.

HereAndAfter Sect03 Sept16 from Steve Paul on Vimeo.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl was recently published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She writes a weekly column on dance for mnartists.org