Glitching the Glass Wall: A Conversation with Autumn Cavender-Wilson

A conversation with glitch artist Autumn Cavender-Wilson on generative tech, Indigenous glitch, and the liberating fluidity of repurposing objects

JULEANA ENRIGHTYour work explores the medium of “digital generative quillwork.” Can you go more in depth on that practice and your creative process?

AUTUMN CAVENDER-WILSONI’m actually not a tech person. I am an avowed Luddite. So, it’s funny and vaguely ironic for me to be working in this space. When the pandemic hit, that’s really when crypto art really started coming onto the scene in a more mainstream way. I was really enchanted and blown away by the use of AI and generative tech.

This is before Midjourney and DALL-E and all of these other things, when it was still weird to use. I wondered if I could train an AI or a program to help train my eye to see geometrics. I started playing around with a lot of generative tech, and getting help from my husband and local glitch artists, asking: How do we hack these programs? How do we change and manipulate them in order to create certain kinds of images?

JEI feel like “experimental” is often the broad buzz word used to describe indescribable bodies of art work. How would you describe your work and why it may fall under this nuanced category, or not at all?

ACWAt this stage, it absolutely was experimental. What can I make this do? Does this work? I came up with a lot of interesting things that were aesthetically Dakota, but not pretty, and didn’t tell a story to me.

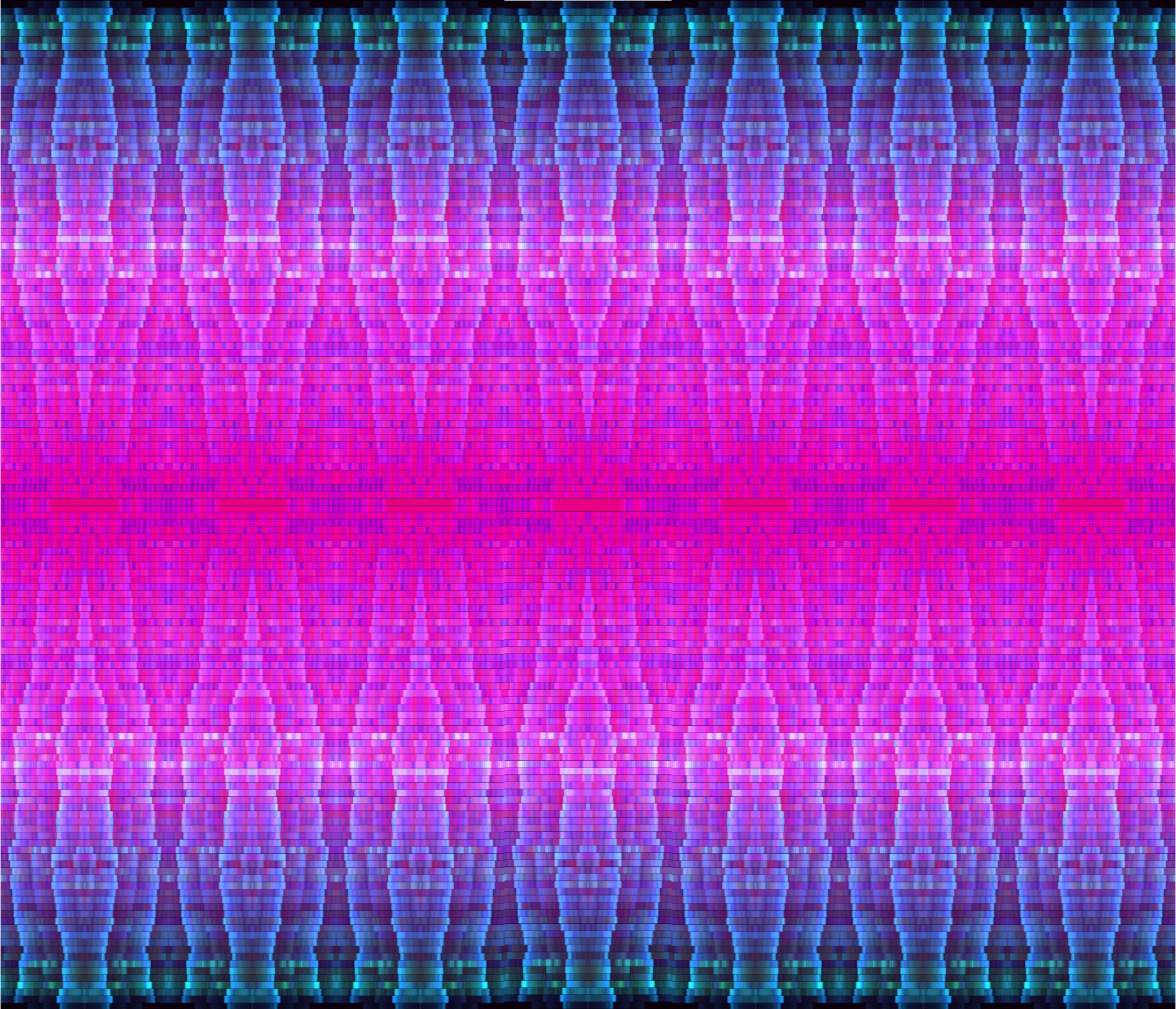

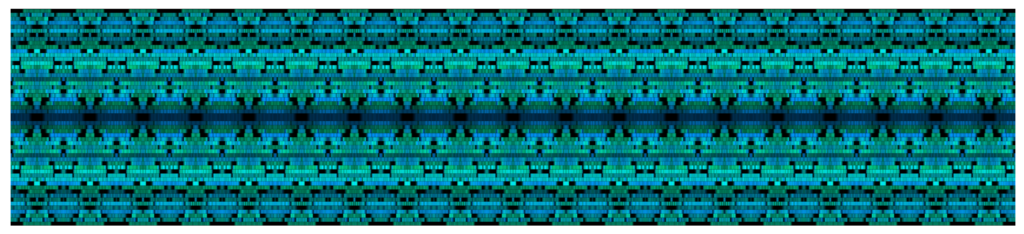

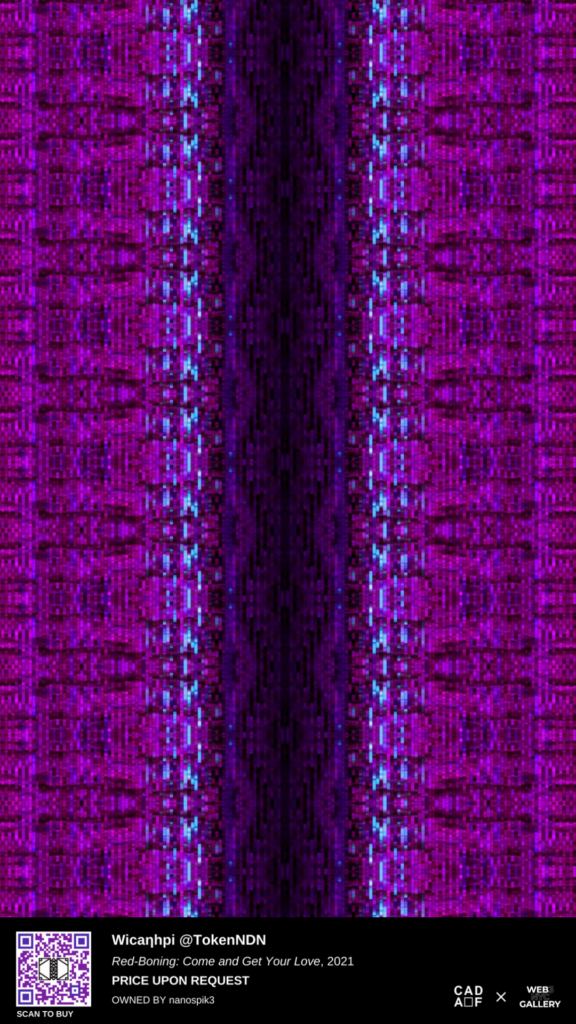

I have to be able to plug information into a program and get a design that is referential to the input. It’s not enough to create a pretty design out of something there. It actually has to be able to tell the story behind it. With this program, audio comes out with a base image. Then that image is taken and manipulated, utilizing a lot of Dakota principles about symmetry and aesthetic, and replicated out into patterns and designs.

We were plugging in an audio track of a war song from a 19th-century wax cylinder recording and I began to see something crazy. It was a marching-off-to-war song, and I could see footprints leading to boats. The more I played with it, modified it, and plugged in, I realized that now I have a piece of technology I can use to directly co-create with an audio file, to produce images that are directly referential to the original input. I think the prime example of this is the song “Odowan 141.” It’s a traditional Dakota melody which was taken by missionaries in the 18th and 19th centuries, and they place their own lyrics to it still in Dakota. This hymnal was the one that was sung by the 38 men in Mankato prior to the lever being pulled.

My grandfather, Dr. Chris Mato Nunpa (retired professor at SMSU), was an ordained Presbyterian minister and a classically trained musician. Over the course of several years he has worked with the Dakota hymnals and their revitalization as a language teaching opportunity. I have this recording of him singing in Dakota “Odowan 141,” which I plugged into the program, and I got these beautiful, stunning images. I also got faces.

The faces themselves were a really fascinating thing to get, and the images were all directly referential to the lyrics of the song. I replicated it out so that there were 38 of these faces, and I had a visual representation of an audio file of one particular song.

If it had been somebody else singing this song, we would’ve gotten different images. But now I have this opportunity to co-create—along with my grandfather and along with his historical ancestral song and ancestral knowledge—a visual representation of this music that is directly referential in utilizing Dakota aesthetic.

I can experiment with that and take those designs that are generated to create physical, wearable pieces. Experimenting with silversmithing, I can take that and use it as a physical song. How do we utilize current, ancestral, and future technologies in order to communicate with non-human intelligences, with ancestral intelligences? Those questions are insanely exciting.

JEYour work explores Dakota techniques of encoding teachings of theology, cosmology, place, and genealogy, and poses the question: “How do we pull these things out of these empirical spaces into physical representations that not only do them justice, but still communicate some of that deeper, underlying truth?” What answers have you encountered through your practice and what questions have been stirred?

ACWThere’s always more questions. What it’s really forced me to do is wrestle with the concept of design, and wrestle with the concept of knowledge. It’s common in Native circles to hear this idea that that knowledge is not lost or that knowledge is living or that we still are able to have access to that. It’s easy to dismiss that as rhetoric, particularly if you have no firsthand experience of that reality.

If we take this idea that knowledge exists on its own—that it is an independent thing that moves through non-linear space—it means that there has always been technology that our people have accessed in order to access knowledge. Oftentimes, when we talk about Native people in tech, we are omitting spiritual tech, we are omitting ancestral tech, and focusing exclusively on Western modern tech—whatever that means.

Through generative quillwork, the designs that come out of that and my lived interactive experience, it’s become clear to me that this knowledge is not lost. It continues to exist, regardless of whether or not any individual living person carries it. It is still accessible. How do we create tech to access that knowledge when the normal tech, or the usual tech in terms of oral tradition or apprenticeships that we have relied upon to transmit that knowledge, is no longer accessible to us?

JEI’m thinking of this specifically in terms of glitch. When we think about a glitch, it’s an error, mistake, failure to function. I’m interested in this concept of glitch as a refusal. I’m thinking about the concept of errors in the system in relation to Native history. The survival, existence, and resistance of Native people is a sort of glitch in the history of colonization from Western society, our constant innate refusal. In Glitch Feminism, Legacy Russell talks about how we can reshape this abstract concept of knowledge—which has been forced into uncomfortable and ill-defined spaces—towards greater agency for us and ourselves. How do you think that fits into what your work does?

ACWAs I’m sitting here musing, I’m wondering to what extent glitch is used by knowledge—knowledge being a non-human intelligence—and that knowledge uses glitch to communicate. It’s a method to access the people to whom that knowledge belongs or is deciding to communicate with, which is a concept I’m going to need to wrestle with.

I was really struck by what you said, and it’s something that I talk a lot about in my education and in my lectures,though I haven’t talked about it in this way. The existence of Indigenous people ourselves is a glitch. It is a glitch in the system of colonialism, it is a glitch in the system of manifest destiny. It’s through that glitch, that mistake in the Western process, that what we have has continued to blossom.

Any introduced colonial technology to any Indigenous nation worldwide is inherently glitched. How we use it is always different from how it was designed, how the dominant paradigm outlines that we should use it.

A hilarious example of this when it comes to just straight-up technology is the tomahawk versus the ax. The ax head was something that was traded because axes themselves were too much, they were just too big. It’s easier to trade an ax head. Europeans have a very weird way of making an ax, one that actually leads to a lot of breakages of the handle and ax heads flying off, versus when Native people came across it and looked at it, they took a V-shaped piece of wood and slid it down the long end. Now you have something that can not only be easily removed and utilized as a different tool, but also doesn’t have the same risks attached to using it as an ax.

Any time Indigenous peoples are interacting with colonial technology, the uses of that are inherently glitched—not just because we’re not supposed to be using them, not just because we’re not supposed to continue to exist, but because we have a different worldview, and that is going to cause that tool to be used very differently.

I’m also thinking about this idea of mythology as a form of tech, the way it is designed to enforce particular worldviews and enforce particular social structures. In that regard, Indigenous peoples and the fact of our existence is also a glitch in the tech of mythology for Western colonialism. We have to continually be disappearing in order for manifest destiny to work, we have to be disappeared in order to be classified as historical. Our flat stubborn refusal to do that, to be convenient in that way, really is a massive glitch in their mythology, and one that they still have not reconciled, one that they still struggle to cope with. The glitch of Indigenous existence forms a major piece of cognitive dissonance in their own morality and in their own way of moving about the world.

JEI’m thinking of Russell’s quote: “We fail to function in a machine that was not built for us.” Instead of succumbing to the pressure to assimilate or conform within a culture that doesn’t love us or recognize us, how do we reconsider what success in a culture is, and how do we use these glitches to create spaces for reclamation and liberation?

ACWIt’s a great quote.

JEAnd obviously, Legacy Russell is talking about this from a very specific place of being a Black queer person, but I think that for the sake of this conversation, we can include Indigenous people. Because what she’s really breaking against is this concept of cisgender white women having a monolithic point of view over what cyber art or glitch art or generative tech can be. The resistance and the veering away from the system that isn’t built for us through these mediums.

ACWI would argue too, there’s this aspect of repurposing that is a hallmark of resiliency, particularly in marginalized and oppressed communities. I would push to include rural folks within this framework—especially having Glitch Art is Dead here in a rural community last year—pushing this conversation of rural places which are often also discarded. They’re considered a flyover, backwards, obsolete.

Glitch art, historically—and especially the aesthetic that I personally see and interact with within the glitch community—is a lot of utilizing obsolete technology in order to create art, and really encountering and wrestling with the idea of what is obsolete. What does that mean, and then, how do we use what is obsolete to create, to make something beautiful?

JEIn what ways does the reclamation of the obsolete show up in your work?

ACWRight now I’m working with the Minnesota Historical Society as the Native American Artist in Residence, and I’m looking at parfleche and the uses of bags, specifically in the work of femmes and women within Dakota society.

It’s beautiful to see all the ways in which parfleche and rawhide are repurposed. You see old parfleche boxes being used as the soles for moccasins, as panels for the quillwork in pipe bags. This idea of repurposing is very fundamental to Dakota ideology and to Dakota cosmology, this idea of regeneration, rebirth, bringing something new into a new space.

Something I emphasize with my quillworking students is that repurposing doesn’t negate the holiness of something. It’s not an insult to the pipe bag to have a reused piece of parfleche used as its panel; it’s not an insult to that same pipe bag to have a panel on it of quillwork that used to be on a shirt. It is a representation, a continuation, an expression of the genealogy of the creation of that piece and how it’s contained and how it’s held to use things that have had previous lives.

Glitch art is a cool way of encountering this idea of uselessness, and pushing back against it. It forces people to think about things differently, and can be used as tools of liberation in oppressed communities.

JEI’m interested in your thoughts on Indigenous reality through a critical lens. Where do you see the parallels between Indigenous Futurism and glitch art?

ACWAs the fundamental principle here, whenever futurism is imagined in any sphere, in any stretch of the word, Indigenous peoples are always omitted. Whether we’re looking at some hyper tech space future or if we’re looking at some post-apocalyptic reality, Native people are always omitted.

As glitch art, the fact that we predate these technologies, we currently exist within their reality—and we will post-date them as well—our continued existence into the future is this fundamental glitch in the system of colonialism. When we talk about technology and Indigenous Futurism, there’s an interesting conversation to be had about the revitalization of these ancestral technologies and the way those will look in the future.

Contemporary ceremonies don’t look how they did in the past. When we talk about the revitalization of ancestral tech within the context of Indigenous Futurism, I imagine it will be very much the same. We are going to glitch these ceremonies, we are going to glitch our interactions, and in the process of our revitalization, it’s going to look recognizable but different within the context of whatever lived reality we have in the future.

Indigenous Futurism, weirdly enough, is not an original concept. This idea of “seven generations forward” is an inherently futuristic idea. Everything that we do, we’re planning for an Indigenous future, every project we engage with is about creating a future for our people and for our grandchildren. How that plugs into this idea of Indigenous Futurism is really in the same way of, how do we utilize quill working methodology in digital technology? How do we apply Indigenous future philosophies to contemporary and future reality? The methodology of planning is still there. How that methodology is enacted in the real world will necessarily have to shift and change.

As long as we continue to encounter technology that was not designed for us, we will have Indigenous glitch. As Native peoples, we have been interacting with cultures that were not our own for millennia. We have always taken and appropriated the technology of other cultures, of other nations of people, and either discarded it as something that didn’t have use/value for our people, or glitched it so that it would. Native glitch is an ancestral practice.

Wicanhpi Iyotan Win Autumn Cavender is an artist, midwife, and activist currently residing in her home territories. She began her journey as an artist through a porcupine quillworking apprenticeship with master quillworkers in 2016. She began her digital art practice through an interest in developing original designs in quillwork and beadwork, and in its appeal to younger generations. Fiercely dedicated to decolonization, land rights, and birth justice, Cavender spends much of her time engaged in community work. She firmly believes in the power of community art and the legacy of craft to heal trauma and spur critical dialogue about Indigenous reality. Currently, she is launching her practice into the digital sphere, and explores the ways in which ancestral practice, generative tech, and the vibrations of sound intersect.

Cavender’s work as a digital artist includes creating Dakota floral designs and templates for personal beadwork, community projects, and public art. Additionally, she uses digital art techniques in her practice of “generative quillwork”. In developing designs and patterns using songs and sounds to explore the design applications of contemporary mediums, she aligns Dakota artistic praxis, rather than trying to fit “Indian” designs into contemporary mediums. This innovative practice is based in Dakota quillwork methodologies and informed by her personal understanding of Dakota techniques of encoding teachings of theology, cosmology, place, and genealogy.