Frankenstein AF

Senah Yeboah-Sampong delivers a fresh reading of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein through a contemporary Afrofuturist lens, considering how bodies come to be read as monsters out of fragility and fear.

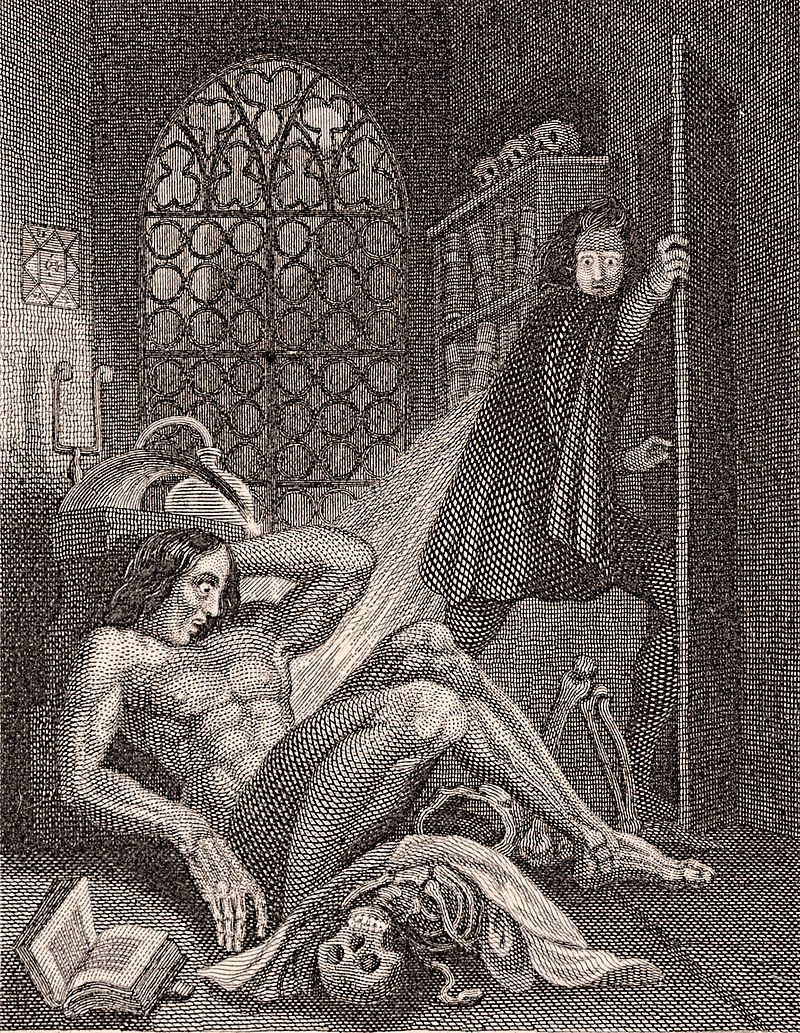

Someone, or something, took the life of a young boy from a well-to-do family. The only suspect was the victim’s housekeeper, Justine. Despite the evidence against her, the family’s eldest brother, Victor Frankenstein, pictured a very different suspect: “The deformity of its aspect, more hideous than belongs to humanity…Could he be…the murderer of my brother? No sooner did that idea cross my imagination, than I became convinced of its truth.”

So begins the central conflict of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: the Modern Prometheus. Writing almost two hundred years before, Shelley captures in her book an allegory, something terrifying, yet essentially unchanged. It speaks to the projection of white fear onto bodies that racism would exploit or eradicate. Instances in which white supremacy and its agents (witting and unwitting alike) call Black humanity into question is one of degree, not sentiment, each stemming from the idea of “Blackness” as something abominable, sub-human, monstrous. Within Frankenstein, the first work of literary science fiction, Shelley confronted similar questions around the potency of imagination and fear, privilege’s pitfalls, and the echoes of unresolved trauma—questions which are paralleled in many subsequent artworks dubbed “Afrofuturist.” These common threads shape Victor and his monster, and are not confined to Shelley’s historical moment.

Depending on where I stand in time and space, my questions of post-apocalypse, post-humanity, and liberation are: Who gets to be human? How, and why? What, then, is the value of that humanity? How do we deal with individuals and collectives embodying humanity in myriad spatial-temporal contexts? How do trauma and genetic memory factor in?

These are Shelley’s questions. Frank Herbert, Isaac Asimov, Octavia Butler, Gordon R. Dickson (the hometown hero) and Ishmael Reed have built some of the most elaborate, enigmatic and undeniable structures on her foundation. Each writer uses science fiction to speak historical truth into the future—or to reimagine the past, who we are, and how we might survive to see something like true liberty won for all people in all times and places.

My efforts to decolonize this foundational text reveal it for the mirror it was, is, and ever shall be. Abandoned by his creator, the unnamed monster’s search for meaning, sympathy, and belonging bind Frankenstein to some of Afrofuturism’s most pressing questions. I am always confronting these questions in some way through any art I create. What does it mean to be human? What are our self-imposed human limitations, and how do we recognize, honor and protect our collective humanity?

Afrofuturism became the web into which I spun those threads. Afrofuturism does more than offer new and oft-marginalized perspectives to the science fiction genre and culture from which it draws inspiration. It allows me to engage with questions of Black liberation, in the future we live today, even through a British aristocrat’s old horror story.

Depending on where I stand in time and space, my questions of post-apocalypse, post-humanity, and liberation are: Who gets to be human? How, and why? What, then, is the value of that humanity?

Shelley never has to explain what we understand intuitively, which is that language is sacred. She demonstrates that sacred aspect by simply showing how time can move us across spatial, temporal, and emotional realities. Frankenstein unfolds through emotionally lush, first person perspectives. We begin in media res with Captain Walton, who rescues the dying Victor in the then-unexplored Arctic Circle. Identifying with Walton’s fatalistic drive to pioneer an uncharted realm, Victor shares his story as a warning. Here the perspective shifts from Walton’s present to Victor’s past. The spoken word, once written, becomes the bridge we cross to stand there with them. In showing rather than telling, and even in telling, Shelley flexes style or modality, the Muntu, as Janheinz Jahn considers in his exploration of Neo-African literature. As a creator and consumer of art, style is an expression of candid authenticity and it is everything. It is the beauty of truth.

Born to wealthy, loving parents, Victor’s body carries markers of patriarchy and white privilege. As a boy, his mother presents him a young girl about his age “as her promised gift.” At university, Victor folds chemistry and mathematics into his focus on natural science. He figures out how to endow “animation upon lifeless matter” and zealously takes to the task. Victor’s long hours of probing, dissection, and needlepoint fuel anxiety and paranoia. His vision, however, much like white supremacy, yields a disturbingly tyrannical bent, as he explains: “A new species would bless me as its creator and source.”

Yet, beholding his labor’s ripened fruit, “The beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart.” He then flees from his monster and suffers a psychotic break, foreshadowing the narrative’s darker turns. Victor reads unexamined fears on to the hulking, superhuman form of what we will learn was, for a time, an innocent soul. Reading Victor’s description of his monster in 1818, echoes for me the “demon” then-officer Darren Wilson made of Michael Brown. As Wilson recalls how he killed Brown in 2014, he reflects the impulse of white imaginations to destroy Blackness out of programmed hatred and confusion for us—and in many ways, themselves.

Mid-recovery, Victor learns that his youngest brother is dead. Though he thinks the monster might be the killer, Victor tells no one of his “research” or its outcome, and Justine is executed. When the monster later confronts a troubled Victor, Shelley pivots into the nested narrative of the monster himself. Having observed humanity from a safe distance, the monster is now articulate and well-reasoned. “’People possessed a method of communicating their experience and feelings…by articulate sounds,’” he tells Victor. “’This was indeed a godlike science, and I ardently desired to become acquainted with it.’”

Not only does the monster speak of language’s power, the monster has also learned how to use that power to make a case for the humanity his own creator denied him, legitimizing the depth and range of his emotion and experiences. The monster reads and learns about his world. The monster is read by others, and is slowly but surely trained to read himself through the same eyes, growing a double consciousness. In his section of the book, the monster owns his narrative in as much as he can separate it from the one he is assigned at birth. He wrote his own history through living it and telling it. He was never a monster, but “monsterized” for the convenience and simplicity of Victor’s fragility and fear.

As I read, I found ongoing debates on respectability politics, double consciousness, code switching and assimilation in my ears. The monster’s body functions much like language, carrying oft-incomplete, culturally specific meanings we may take for granted as universal or objective. The monster, read as “monster,” is then beaten, shot, insulted, and so forth.

Shelley obliquely, perhaps unwittingly, frames “language” as a high technology. She also exposes its inability to show us anything outside of what we can feel or conceive. Finally, Shelley displays language’s acute capacity to limit how we understand ourselves, and are understood by the worlds we are born into. Tragically, neither Victor nor his monster are able to acknowledge the trauma at the root of their conflict, or shake the sense that their roles are fixed. They parlay, then repeatedly clash. The power dynamic flips, roles reverse, and hatred consumes, until each is destroyed in his turn.

As I read, I found ongoing debates on respectability politics, double consciousness, code switching and assimilation in my ears. The monster’s body functions much like language, carrying oft-incomplete, culturally specific meanings we may take for granted as universal or objective.

I finished the book, then considered the warnings I imagine Shelley, primed for future shock, hid in plain sight. She was the child of a notable proto-feminist, and a contemporary of some of the greatest Romantic poets of the age. Yet, it seemed much of her subtext went overlooked, as if the form, not the substance of her work, was more palatable to the gatekeepers.

So, H.P. Lovecraft could be a racist. Africans could be “proven” genetically “inferior” to whites, First Nations peoples sequestered and slandered…unless we take Frankenstein and other posthuman parables and read closely. Then, perhaps, everyone might agree that Mike Brown (or Castile, or Edwards, or Bland, or Gaines, or Scott, or the Emmanuel Nine, or…) was human, before anything else, that “bad apples” can’t overstand shortsighted implicit biases, or close psychic wounds with band-aids and lip service.

As a Black person, a nerd, a writer, I find that what I am and what I create are both abominable and marvelous. I know in order to get the large picture, both marvel and abomination must then be embraced. In days of future past, Afrofuturism—as analytical framework, artistic practice and aesthetic—could help us patch together lost or overlooked fragments of our Black, human history. The truth of me is the truth of you. It is the bits and pieces that I can make sense of, stitch together, breathe life into. With a new framework to decolonize science fiction, I aim to go boldly, whatever the case may be.

This article was commissioned and developed as part of a series by guest editors Free Black Dirt.