Afro-Indigenous Futurisms and Decolonizing Our Minds

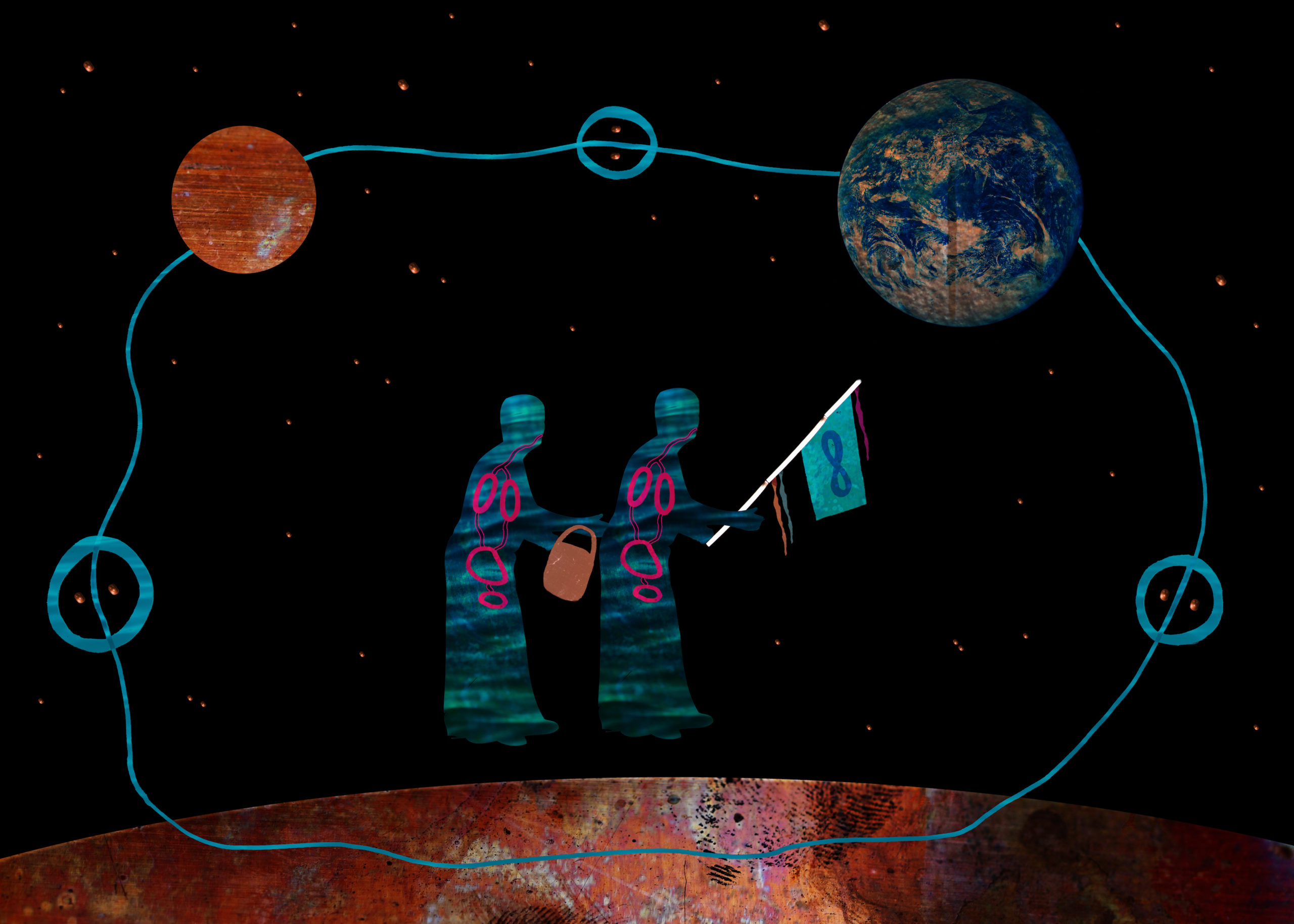

Introducing a series of essays addressing the intertwined Afro-Indigenous histories of colonized life and demanding futures of decolonization in art and community.

Indigenous art is often perceived as resistance when, in fact, it is our very existence which is an act of resistance.

Elizabeth LaPensée

A parallel to Afrofuturism, Indigenous Futurism (coined by Anishinaabe professor Dr. Grace Dillon) is a reclamation of Indigenous sovereignty from mainstream media. Transcending past, present, and future, it “imagines a world where colonization hasn’t disrupted the civilization of Indigenous people” and the representation of Indigenous people hasn’t been skewed in favor of the colonial project. In this editorial series, I invite Black, Brown and Native narratives and agency to the forefront, gesturing toward collective acts of resistance amid present-day modes of systemic racism and erasure. By creating a glimpse of who came before us, who may come after us, and those who stand at the precipice of those unions, we address the intertwined Afro-Indigenous histories of colonized life and demand futures of decolonization in art and community.

As a light-skinned Native American of Sinchangu Lakota descent, I would be remiss not to address that I am residing on stolen Dakota land, and provide acknowledgment of those who came before me. Ancestors whose bodies held pain, power, and knowledge, whose existence was a form of resistance, and whose resilience and struggles of oppression I hold in my body as a blood memory. While carrying the currency of my own “white-passing” body, I am here because of my relatives’ refusal to be wiped out by genocide, refusal to have their culture dismantled by white oppressors, and continual fight to preserve language through storytelling of their own narrative. I think of the opening minutes of the Indigenous Futurisms mixtape, collaboratively produced between RPM and the Native-produced kimiwan zine, where Leanne Simpson envisions for us a world of reparations and justice:

Speak to me of justice when the beneficiaries of genocide feel the anguish of my ancestors and beg our forgiveness. When every one of the inheritors of stolen land engages in personal and collective acts of reparative justice. When 38 white men swing from the gallows in Mankato…When our language is brought back from the edge of extinction. When our people return from exile.

Envisioning Black, Brown and Indigenous bodies throughout time and space, thriving in every space and time, dismantles the belief that we are relics of the past (as colonial paradigms would have us believe), stuck in a world in which settler colonialism has left us. This stretches beyond a mere understanding of the history of colonization, but addresses how a system of white supremacy, superiority, and privilege has seeped into our own mindsets—from colorism to white guilt, from privilege to access. It is a process of constant learning and unlearning, and of cultivating pleasure where we can.

For oppressed people to intentionally cultivate pleasure is an act of resistance.

Ingrid LaFleur

The colonial experience is nothing unique to us as Native people. It’s worldwide. So there’s that connective tissue between all of us. So using that experience, transforming it into something funny and really exposing it for how dysfunctionally funny it is, it helps. It breaks down those barriers between our communities and brings us together.

Dallas Goldtooth on laughter as a collective aspect of trauma response

As Black and Native people continually witness an ongoing assault against our communities and culture, how do we push through the dystopia of whiteness by using the rehearsal of our existence as resistance? When will we be able to speak of justice, when justice was never meant to serve and protect Black, Brown and Indigenous bodies? What is the pathway to an equitable future? Can inviting ourselves into cosmic spaces that transcend time and reality free our minds?

Often heralded the “mother of Afrofuturism” for her alternative communities and imaginative landscapes drawn from African race and culture, Octavia E. Butler’s work in speculative fiction signaled towards a “dark colonial past” to reveal the emergence of the imaginary. Butler’s dystopian classic, Parable of the Sower, is disturbingly poignant: we exist now in the futuristic decade in which it was set, and the novel’s early 2020s environment disturbingly mirrors our current world of global climate change, economic crisis and social chaos. In its intro, her protagonist Lauren Oya Olamina, the creator of the fictional Earthseed religion, which is based on the idea that “God is Change”, speaks to omnipresence through resilience:

Prodigy is, at its essence, adaptability and persistent, positive obsession. Without persistence, what remains is an enthusiasm of the moment. Without adaptability, what remains may be channeled into destructive fanaticism. Without positive obsession, there is nothing at all.

Through the lens of work like Parable of the Sower, or Saskatchewan-born Cree/Métis writer/director Danis Goulet’s Wakening, there is an opportunity for those whose histories were not disrupted by colonization to visit a world under occupation. With these representations in film, lit, music, visual arts and pop culture which riff off of the tropes of origin to explore alternate histories and timelines, we are called to explore themes of Black and Indigenous “resistance, reconciliation, and identity via visual storytelling mediums.”

As a cultural and artistic movement, LaFleur believes that Afrofuturism is an essential lens for looking at systems change, because it “empowers Black people to imagine their role in the future, even when the current reality is one of systemic discrimination, mass incarceration and state violence…and offers a beautiful, almost entertaining, seductive approach to think about the decolonial process. Another example of cultivating pleasure where we can.

There’s truly never been a better time to investigate how Afro and Indigenous Futurism can empower future realities for BIPOC and allow for collective healing and liberation, because it involves not simply building on top of a cracked, crumbling, and corrupt foundation, but building without a foundation. In our current climate, while calls are being made to abolish police, dismantle prison structures and level-up on anti-racist work (both in self and society), while uprisings and protests are forcing those previously silent to examine their roles in systemic racism, combining our past knowledge of culture and traditions with futuristic utopian societies is essential. By dissecting the frontiers of Afro and Indigenous histories (past, present and future), the challenge no longer becomes how to reform a system of oppression, designed to work just as it has in keeping marginalized groups of people without power—but instead asks how to shift consciousness to decolonize our own minds and reclaim what it rightfully ours: land, agency, narrative.

We need to be more self-reflective…work to decolonize our own minds…without doing that self-check, you’re likely going to do more harm than good.

Ingrid LaFleur

This is not to say that self-reflection, and self-reflection solely, is the solution to generational systemic racism. There is a responsibility that goes beyond the individual. Retracing Simpson’s words of returning land back to Indigenous people, I think about the ongoing desecration where Mount Rushmore is situated, on the sacred Paha Sapa (Black Hills), a signifier of the constant battle to remove statues and memorial tributes of white historical figures whose very presence exemplifies the eradication of culture, language, existence. Opposed by the Lakota people for generations, how would the closure of the national monument indefinitely change the narrative for Indigenous people? Where are the reparations which are due to forge collective healing?

Listening to the stories and teachings of those who came before us to help us live intentionally with responsibility. Our actions in this moment inform possible futures for those who will continue on after us. This is especially vital for the balanced wellbeing of lands, waters, and all interconnected life.

Elizabeth LaPensée (citing Cajete, 2000; Wildcat, 2005; Freeland, 2015)