What Does a Black Liberation Future Look Like?

To catalyze their editorial work with Mn Artists, Free Black Dirt hosted a dinner and curated conversation on the topics of Afrofuturism, healing, prison abolition and transformation. A video by Adja Gildersleve captures the highlights.

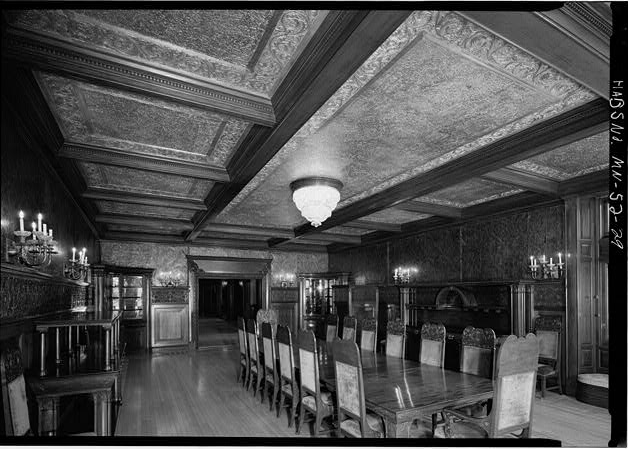

When we first visited the James J. Hill House on Summit Hill in St. Paul, it was the leather wallpaper in the dining room that stopped us. The walls were covered with the rippled skin of an animal—no, dozens of animals. The tour guide said that Hill had imported the hide from the U.S. Virgin Islands, that he had imported the wood for the ornate hand-carved woodwork as well. The ceiling was gilded gold. There was a partition on one of the walls. It was meant for hiding. It was meant for the servants to peer through the slats until they were summoned.

The James J. Hill House was not first on our list of possible venues for a dinner themed around Afrofuturism, an extension of our editorial work with Mn Artists. It quickly rose to the top of the list when we could see it as a reckoning with the past. Isn’t Afrofuturism about contending with the past? Isn’t it about reimaging time and the spaces marked by it?

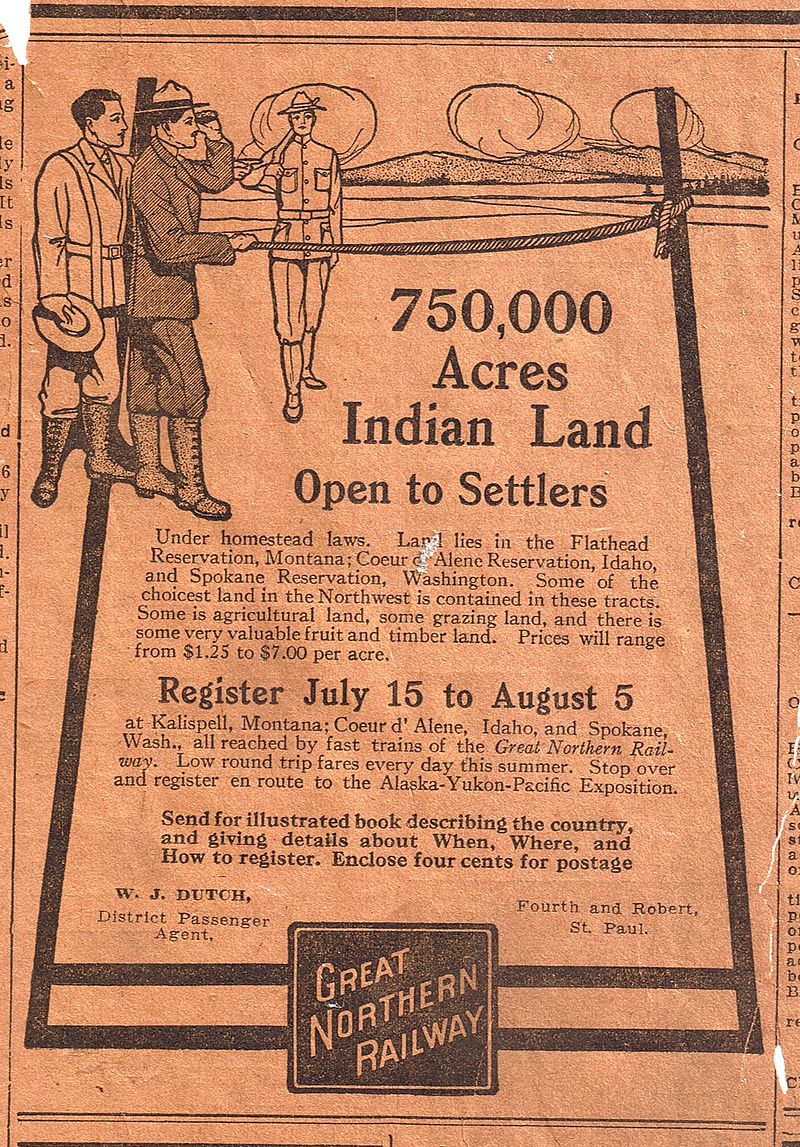

In many ways, Minnesota was developed the way it developed because of the railroad. And here time matters too. James J. Hill, the Empire Builder, had laid the first ten miles of rail by July of 1862. That year was important. Remember the Homestead Act, which offered to settlers 750,000 acres of land stolen from the Dakota? That was 1862. Remember the Dakota War, started with treaties broken by the U.S. government and ending with the largest mass execution is U.S. history and years of displacement and exile for the Dakota–1862, too.

There are many places in Minnesota that do not feel like our places. Places stolen long ago and fenced off for the rich, like North Oaks—once Hill’s hobby farm, now the richest community in the state—or places claimed and named for the warmonger Calhoun, like the lake that had its name recently restored, Bde Maka Ska.

Places designed for us to stay hidden and invisible and waiting to serve the interests of the wealthy and powerful.

When we toured the James J. Hill House in search of a place for this conversation, we wanted a place where we could be voluminous—not just a place to eat, but to take up space with our bodies and our voices. And we did that. With an incredible group of artists and writers, we imagined boldly how we can look to the future, without mimicking the development patterns that have made this place.

This video is a record of our conversation.

This article was commissioned and developed as part of a series by guest editors Free Black Dirt.