Fool’s Gold

On looking, seeing, and feeling ancestors and their stories of survival as mentorship

We all know sometimes life's hates and troubles Can make you wish you were born in another time and space But you can bet your life times that and twice its double That God knew exactly where he wanted you to be placed So make sure when you say you're in it, but not of it You're not helping to make this earth a place sometimes called Hell Change your words into truth and then change that truth into love And maybe our children's grandchildren And their great-grandchildren will tell

“As,” Songs in the Key of Life, Stevie Wonder

“Hey! Stop running. Come here and let me look at you, girl,” my great aunt Reola said.

Aunt Reola was my papaw’s big sister. There was only one nursing home because Sparta, Randolph County, Illinois was a small, historic town, part of the Underground Railroad, with only one of everything, and Aunt Reola lived in their one convalescent home.1

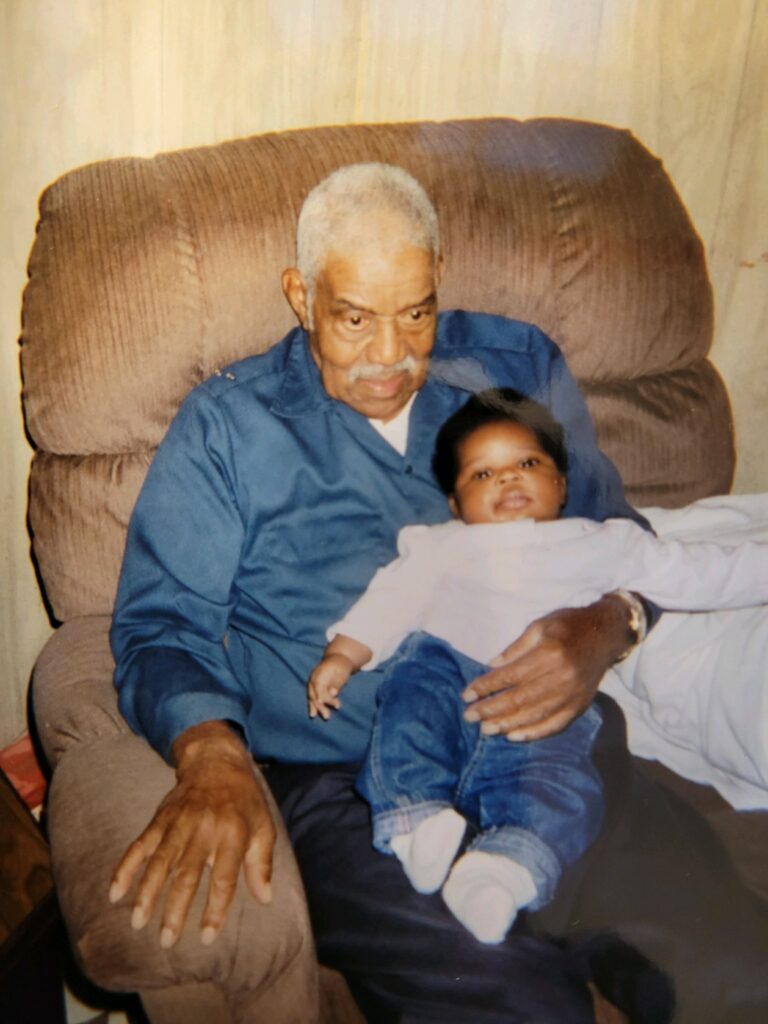

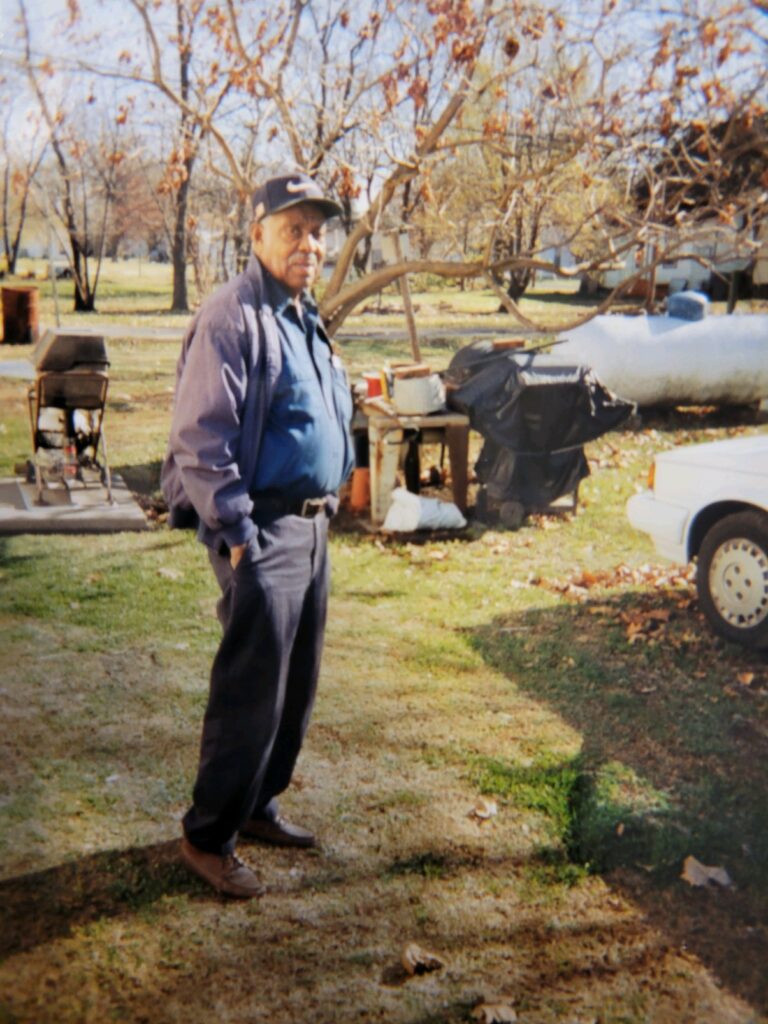

On Sundays, my papaw would go get Aunt Reola in the morning, and she would spend the day with us, sitting quietly in my grandma’s green chair, watching Westerns and WWE matches on the big, floor-model TV with my papaw, and eating supper with us before my papaw would return her to the nursing home.

“Hi,” I said, as I entered the house from the front porch, while the ripe smells of recently picked tomatoes, green beans, and cucumbers waiting patiently in wooden baskets for canning filled my nose.

I was thirsty, and like a bullet, I had entered my grandma’s shotgun home from playing running bases outside in the August sun. I was out of breath, but showing the right amount of respect for my elders as I tried to continue skipping past my Aunt Reola and her words, making sure that I didn’t run over her diabetic feet. My older sister and I were making the best of our last few weeks visiting our grandparents, before our mother would drive down from Chicago to get us back to the city in enough time to start the new school year.

When I was a little kid, I thought that one of the coolest things in the world to do was being able to pee in a blue water toilet on a moving bus.

While I was middle-school age, my single mother shipped me and my older sister by Greyhound bus from the 95th Street and Dan Ryan Station to East St. Louis once school let out for the summer. My strong, beautiful mother, turned scandalous wife of a too-dark Black city slicker by gossip and subsequent divorce, was convinced that me and my sister running the dusty red chat-lined roads without sidewalks in the small town of her birth would be much safer than spending latchkey 1980s summers alone in our South Side Chicago home, while she went to work every day.

With our cold fried chicken sandwiches and cans of red pop2 rolled precisely in grocery store brown paper bags, and relentless warnings to not talk to or sit next to any strangers, and to not sit directly on the bus toilet when we went to the bathroom, our grandparents would meet and pick us up at the Greyhound station in East St. Louis as long as we arrived there “before dark”: my grandma’s words.

After one hour of car driving deeper south into the Land of Lincoln on hilly, meandering two-lane roads between wafts of manure, newly planted corn and soybean fields, and set-back strip-pit lakes, when we finally crossed the Kaskaskia River3 (a tributary of the Mississippi River that separates the southern part of the state from Missouri) into Randolph County, I knew that we had arrived at the place that was my summer home, my mother’s and her people’s home.

My grandparents’ 19th-century home was in the small, expatriate-named, southern Illinois town of Sparta.4 Originally, part of French colonial country from the very late 17th century, it became part of French Louisiana5 and then remained under British control until the American Revolution. Some of our family members—Black, white, German, and Indigenous6—came to Illinois from the Carolinas, Louisiana, Missouri, Germany, and intersected in Randolph County.

My grandma’s house had yellow siding and central air. From the front porch, you could see the entire house in this order: the living room, the one bureau and bathroom hallway, and the green kitchen in the very back with two separate bedroom additions on its right side.

“Let me see you for a minute, girl,” Aunt Reola said.

She grabbed my left arm, stopping me in mid-stride. She smelled like peppermint chewing gum and coffee. I was surprised at how smooth her hands felt against my brown skin, as she ran them down my arm until she reached my hand, which forced me to turn my body to stand straight in front of hers.

At 11 years old in 1981, I was a big girl. I was tall enough to face her, almost eye to eye, as I stood directly in front of Aunt Reola while she sat in the sofa chair. Next to her was a wooden side table with a lamp. She pulled me near the light, so she could see me better.

Initially, I tried to resist and pull away, but gently, she squeezed my hands, touching all of my fingers one by one as she pulled me even closer to the bright light and to her face. Finally, realizing that strength did not have to hurt, I relaxed my body into hers and surrendered.

Aunt Reola’s glass-covered brown eyes, which seemed to be rimmed in blue mist, carefully studied my face for what seemed like forever as she smiled wide. Her hands were as soft as the words she spoke to me, like she had discovered a treasure chest of gold that only she could see.

“Do you know that you look just like my sister, little girl? She’s been long gone now, but you have her same exact eyes. So big. So brown. So pretty. You look just like her,” she emphasized each word with a shake of her hands in mine, before gently bringing her hands to frame my chocolate, chubby, round face.

A rediscovered joy at experiencing a deep feeling, thought forever lost, emanated from my Aunt Reola’s face, and its realness made me uncomfortable. For a moment, I believed that Aunt Reola, looking dead-straight at me, really believed, if not fully felt, that I was her actual sister.

“No,” was the best response I had, as I really didn’t know what else to say or do.

Aunt Reola was one of the few family members on my mother’s side that did not comment on my being and physical looks in terms of how much darker my skin was than my mother’s, or how big my feet were because I did not like to wear shoes ever, or how fat I was. I could count on one hand how many times I had met Aunt Reola. I knew that she and her brother, my papaw, were the last of their living siblings. Their family had made their way to southern Illinois from the Carolinas.

As a kid, I just thought that’s how things were in everyone’s families. Family members, especially elders, came from other places in the southern United States that folks didn’t talk about; you were described or designated by family elders as blue black, black, red, redbone, high-yellow, or passing;7 family members died young; and you were lucky to grow old and have all your teeth or to be able to afford dentures if you did not have your teeth. The fact that my grandparents owned their own home that had an inside toilet after the birth of my oldest sister, had central air, paid for cable, had a running car, and had a set of dentures, each—one for my grandma and one for my papaw—was the equivalent of “having made it” for them, as Black people living in a small town in southern Illinois in the 70s and 80s.

While looking at me, Aunt Reola had this faraway look in her eyes, as if looking at me made her feel young, like a little girl again, and not an old, brittle woman so incapable of taking care of herself that she had to live in a nursing home with total strangers, without the companionship of her sister. As she watched me with great curiosity, almost like she was trying to convince herself that I was not her actual sister, I thought of all the fun that she must have had with her sister, like I had with my sister when she wasn’t being mean to me. I also thought of how much Aunt Reola must have loved and missed her sister, and I was ready for her to talk more about my dead great aunt that I never had the opportunity to meet, but she said entirely something else.

“Like my sister, your eyes show too much, baby. You see too much. I feel so sorry for you. You are too sensitive, and you will have to learn how not to show everything you think and feel through your face…through your eyes,” she ended.

Aunt Reola’s soft hands, brown like mine, left my face, touched my cornrow braids and trailed down to their multicolored glass-beaded ends, finally journeying to my shoulders and back down my arms to tightly grab my hands again.

I remember feeling like it wasn’t a real question or something that I could respond to. I felt awkward, but so very curious at the same time. Then, I knew I didn’t understand the full meaning of Aunt Reola’s words. I didn’t understand her warning.

I thought that maybe my Aunt Reola might have been making fun of me because I collected all the mines dollars that my papaw and uncles gave me. My papaw, when he was younger and my uncles all worked in the coal mines, they always brought home these mine dollars, pyrite sun, or “fool’s gold,” as my grandma called them.8 No one ever wanted the brass-colored mine dollars but me.

“Everything that glitter ain’t gold,” my grandma would say, and follow it up with: “The shit’s worthless!”

But I would keep the yellow and brassy-colored metals and hide them. I thought then, and still do, that they were beautiful. Maybe this is what Aunt Reola was talking about. She saw how much interest I had in small things and how that interest brought me so much joy or pain, and I showed it.

Now, as an adult, I know that Aunt Reola saw me and felt sorry for me because she knew that I was the kid that saw, heard, and felt everything, even when I didn’t understand it all, and when the adults thought that I wasn’t looking, listening, or feeling. Aunt Reola knew that I was the kid that boldly looked adults in the face, despite their threats of getting a fresh green tree switch to my bare brown legs. How did she know I was always the one who got in trouble for looking adults in the face, for always asking the wrong questions, or “being too grown and nosy”?

My father, who is one generation removed from Mississippi and Arkansas,9 tells the story, from before my mother left him, of taking me and my sister to our neighborhood grocery store in Chicago. I was three years old, and we were waiting in the checkout line to pay for our food. There was a woman standing in front of us, and I was looking up at her. She had a dark brown birthmark that covered half of her face. My father says that I walked up to the lady, touched her hand, and asked her a very sincere and loud question in the way that only three-year-olds can.

“Does that thing on your face hurt? Can I touch it?”

“No. It doesn’t hurt,” the woman said simply.

My father snatched me up and apologized to the woman before I could find out if she was gonna let me touch her face.

When we arrived back home from the grocery store, my father sent me to my bedroom, he put away the food, and I got a whipping with my father’s South Side Chicago belt instead of with a green Sparta tree switch.

“Do you want me to whip her again, Ron?” I heard my mother ask my father after he retold her what happened in the grocery store. I felt so betrayed. I thought one belt whipping was enough.

My father tells that story now with functional liquor and laughter. He says that as a Black man, an unemployed college dropout, a 22-year-old father of two kids under the age of four living in Jim Crow Chicago10 in the 70s, and married to a Black Catholic woman without reliable and safe birth control, he was very embarrassed by my loudness, my impulsiveness, and my spirited inquisitiveness. According to my father, I didn’t know how to act. I didn’t know my place.

As a mother of three children now, it hard for me to ever imagine that a child asking smart questions and critically interacting with their environment could be a bad thing—a thing so bad that it required punishment.

“You never stopped talking and asking questions,” my father says.

Clearly, I didn’t get it. This was the man who had introduced me and my sister to Sesame Street and Electric Company11 by the time I was three years old! What did he think was going to happen?

I now hold my father’s story, and others, in me, like hidden pieces of candy in my pocket or in the damp middle inside of my bra, adjacent to my heart, that I am waiting for the right time and space to take out, unwrap, taste, eat, and savor. With compassion, empathy, and working on “no judgment,” I now know that my father was very afraid. He believed that he had to break me of my fearlessness. He believed he had to break me of asking critical questions. He believed he had to break me of trying to understand. He believed that he had to break me of trying to travel and move into the people, places, and spaces of interaction in the world, my world, and becoming me. Maybe this is what my Aunt Reola saw in me on that late summer day in August of 1981.

I stood there in front of Aunt Reola. After a couple of seconds, I just felt awkward and wanted to go get a drink of water.

Now, as a writer who has aged, I can use my memory and words to return to that moment to see and understand more of what was there.

I realize now that my soul’s job has always been to look and to try to see the past, the present, and the future, and to use my experiences, my empathy, and my compassion to teach and to write, i.e., record and bear witness to my family’s and my ancestors’ (human) experiences, as their lives and their abilities to survive, to thrive, and to love the best way they knew how were and are the very foundation and essence of my own life, making sense of my experiences, and my existence.

In that way, Aunt Reola, like many of my relatives and ancestors and their stories, were and are my best writing mentors.

How could I know that with every interaction with my family members, relative to their and my experiences, even the ones that I did not understand nor enjoy, would become like a map, a trail of hot and spicy pork rinds or sock-it-to me cake crumbs, that they were leaving me, consciously and subconsciously?

The internal and personal. The external. The universal. The human.

Their stories, joy, pain, suffering, survival, oppression, exploitation, struggles, and anger (among infinite emotions) were the clues and coordinates to be able to return to one day, if and when I have the courage to continue looking and seeing. If and when I have the discipline and commitment to continue writing and journeying along those lines, those maps, wherever it and they may take me. In that way, I am merely honoring my ancestors and doing what they did so that their legacies can continue, as their sacrifice and very defiance to survive, thrive, and love the best they knew how and could has afforded me an education, literacy, and my ability to purchase paper and pen and to write myself, my family, my ancestors, and us into existence, into freedom, and into humanity.

For what is the true value of believed gold to its owner that the world mistakes for and treats like a fool?

So, when I start to create, to write, and to tell stories, I know that my ancestors are with me. It is a collaborative and cumulative process, and if I am worthy, I become a vessel to tell my stories and humbly understand that they are not just my stories. They are stories contributing to a larger collective that works to document and evidence the human and soul experience, but more importantly, I hope that they demonstrate beauty, empathy, compassion, respect, growth, and hopefully discovery, love, transformation, and humanity. Ideally, art.

Aunt Reola knew, if not directly or intuitively, that I was the looker, the watcher, the seer, and the listener, the feeler, the valuer, the crier, the teller, i.e., the fool. The empath that felt, reordered, and continues to feel and record what interests me, what affects me, and what I can see and tell.

My ancestors mentored and mused me through trusting me with their words, their stories, their memories, and their love the best way that they could show it and tell it. As the preceding generation, they had poured into me so that I could have better than they did, even if better was sleeping on the floor like they did. I slept on a floor with a warm pallet of thick blankets that my profanity-filled and green tree switch-swinging grandma made for me, and it was the softest bed that I ever have ever known.

My Aunt Reola saw all that in me. She seemed to know that I was that person in the family. She saw the storyteller in me, and while she clearly felt sorry for me, she also found some way to warn, affirm, soothe, and orient me.

I understood then from Aunt Reola’s words that my brown eyes were not mine. They were a gift from her sister who I had never met or heard of, only that she had died long before I was born, like many of papaw’s family members. They are the eyes of a writer: sensitive, fractured, and obsessive in details and memory because my calling, i.e., vocation, is to first see and feel, recount, read, write, and speak the story in prose or poetry when, where, and how it feels and vibrates to me and through me.

If I do my job well, the story then documents that we and they exist and existed, live and lived, survive and survived, thrive and thrived, love and loved, and were and are so worthy. I am, and we are, human and have humanity.

As a mentor, Aunt Reola affirmed all those qualities in me that the adults and others around me defined as bad. I now know that she saw it as a gift and calling. What greater mentor and muse can one have?

According to historian Carol Pirtle, Susan Borders, “Sukey,” a Black woman, was brought to live and work in the Sparta area along with her three sons as indentured servants, “de facto slaves,” by Sukey’s white master, wealthy Randolph County land owner Andrew Borders, from the state of Georgia in the first half of the 19th century.12 Once arriving in southern Illinois, Sukey traveled on the Underground Railroad with her three children, Jarrot, Anderson, and Harrison, with the help of local white abolitionist, William Hayes. Ultimately, Sukey’s three children would be captured, returned to “slavery,” and remain enslaved as far as the records show. Sukey, a mother, would live the rest of her life free but without her three children.

Was Sukey a fool to determine and act upon her and her children’s worth, between the seemingly continuous traveling and moving spaces and places of de facto and de jure slavery13 in the United States of America?

Having three children of my own, still traveling and living north like my ancestors, as I and my husband and our children live in the state known as The North Star, I cannot begin to imagine Sukey’s pain, my ancestors’ pain, and the pain of any parent that is separated from their child as a result of structural, racial, gendered, and class oppression and violence.

However, like a descendant of an oppressed people who have experienced generational trauma, my papaw, like his sister, must have known that his job was to merely tell the stories, his stories, as best he could. Held captive by my childhood, my sensitivity, my respect, and my love for my elders, i.e. my foolishness, my papaw knew that I would listen. He must have known that I was a writer, and when the time was right, I would retell those same stories, and Sukey’s family story, to my children and to the world.

As I sit here in Minnesota in 2023 with my beautiful, fearless, Black children, I just write and tell them my stories, knowing that we are all still moving north, simultaneously a physical and spiritual location, defying time and space, trying to love and to travel and move just to get and be free.

Maybe my Aunt Reola understood, a Black woman descendant of African slaves in the Americas, that the ultimate freedom was the ability to tell your story, and like the Underground Railroad that carried escaped Black slaves through Sparta, Illinois, my ancestors placed and carried their stories in their DNA, in me. I became the safehouse to get them free, and like my ancestors, I write my words to and for myself and my children, in the hopes that they will be freer than me.

“Reola! Leave that girl alone,” my papaw hissed at her. Aunt Reola looked at me, smiled, and let me go. She waved her hand in the air at her brother, my papaw, for good measure.

“Bye,” I said to my Aunt Reola.

I used the bathroom, washed my hands, and bent down to put my mouth on the silver metal faucet and drank some water directly from the kitchen sink. Once done, I rushed back past my Aunt Reola, extra careful not to step on her feet, and made my way back outside.

Later, after a supper of fried potatoes with onions, round steak, and green beans, I will ride with my papaw to return Aunt Reola to the one nursing home. Once we drop her off and say our goodbyes, I will get to ride up front in the passenger seat right next to my papaw, and he will slowly take the scenic route back to my grandma’s house. He will painstakingly point out the schoolhouse at the top of Eden’s Hill and the burnt red brick homes on Sparta’s main street that were stations that conducted passengers north to freedom on the Underground Railroad. He will tell me general stories of slaves and Indigenous peoples; he will tell me that Spirits live in the trees, so it is important to respect them; he will show me how to read the tops of tree leaves that forewarn of bad storms; and he will tell me not to be afraid when I see Spirits, because I should only fear the living and not the dead.

“The dead are not like the living. If you don’t mess with them, they won’t mess with you,” he will say.

At the time, I will just sit in the front seat of the car, not fully understanding but still hearing, absorbing, and enjoying everything that my papaw will say and show me in the soft southern Illinois, removed from the Carolinas, cadence of his voice while he will drive us around. It will be many years later, as an adult and after my papaw’s, Aunt Reola’s, and my grandma’s deaths, that I will match my papaw’s stories and his voice’s cadence with my own Chicago and Minnesota voice and stories, and with the story and voice of escaped Black female mother and slave, Susan “Sukey” Borders, while writing this essay.