Eyes Wide Shut — Karel Funk

Artist and occasional critic Ruben Nusz took in the exhibition of paintings by Karel Funk at the Rochester Art Center -- read on for his incisive thoughts on the virtuosic technique and formal intelligence behind the work on view.

WHEN WE CLOSE OUR EYES WE HOPE FOR DARKNESS, a sense of quiet. But what we usually end up with behind our eyelids is anything but restful: flickering streams of disjointed images pilfered from the cultural ephemera all around us, churned up by the chaotic roil of our disobedient monkey minds.

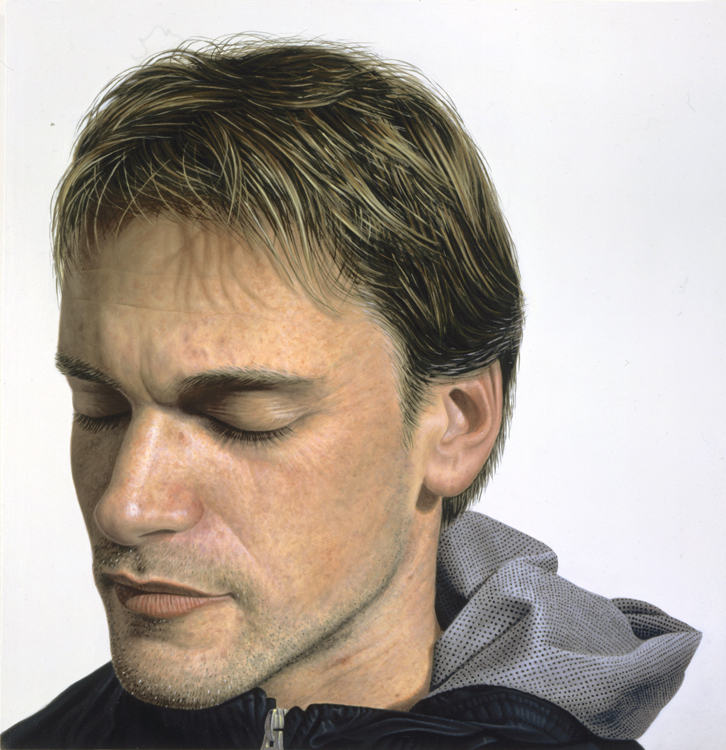

The best paintings anchor our thoughts, urging us to focus our brainwaves on what’s right in front of us in the present moment. Karel Funk’s breathtaking exhibit at the Rochester Art Center accords the mind such a respite. His neo-Renaissance, hyperrealist portraits (mostly of figures with their eyes closed) serve to glorify stillness and cogitation, reiterating — yet again — painting’s continued relevance in the contemporary art canon.

Born just north of us, in Winnipeg, Canada, Funk was schooled in New York before moving back to his hometown, where he now paints in the basement of his house. Each piece takes him months to complete; this time spent laboring is clearly evident in the resultant, almost three-dimensional, paintings – works which seem to burst free of the photographic molds that constrain most photorealism.

As with his contemporaries in the genre, Ron Mueck or Chuck Close, Funk achieves an astounding level of detail in his paintings. According to the artist, this style was spawned from the intimacy of the urban crush, the close proximity to other people he experienced while riding in New York subways and elevators.

In works like Untitled #7 Funk’s minute brush acts like a mechanical hummingbird, scattering small bits of paint on the hardboard with robotic precision; it’s almost as if Charles Sheeler had returned from the dead to paint portraits. More likely, Funk’s style stems from the early Renaissance, inspired by the stiff sitters of Albrecht Durer, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and Giotto.

Echoing the technique of these past masters, Funk layers multiple colors using a fine sable brush. Less economical than, say, Peter Paul Rubens, the work still stuns the viewer into almost passive submission to its detail. In lieu of oil, Funk assembles his layers with thinned acrylic, handled like the egg tempera work made famous by Giotto, who perfected this layered technique prior to the popularization and technical development of oil painting.

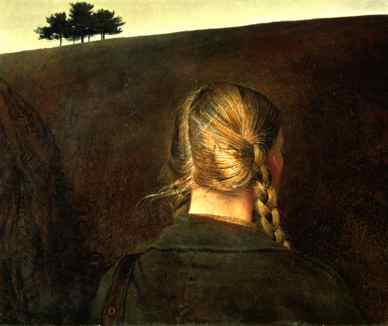

Jump forward in time six hundred years, and cross the ocean from Europe to the Americas, and you see the strategy reinvented by beloved American painter Andrew Wyeth. I’ve always been quite fond of Wyeth’s egg tempera paintings, and Funk pulls from them liberally; both artists build luminosity without really blending – it’s especially evident when you look closely at the figures’ hair. When painting with oils, the best painters, like Rubens, approximate hair using a thick brush’s bristles to distill highlights and lowlights. In contrast, Funk, like Wyeth, paints every single hair strand. The effect can be either tiresome or astounding, depending on the deftness of the artist; Funk succeeds marvelously.

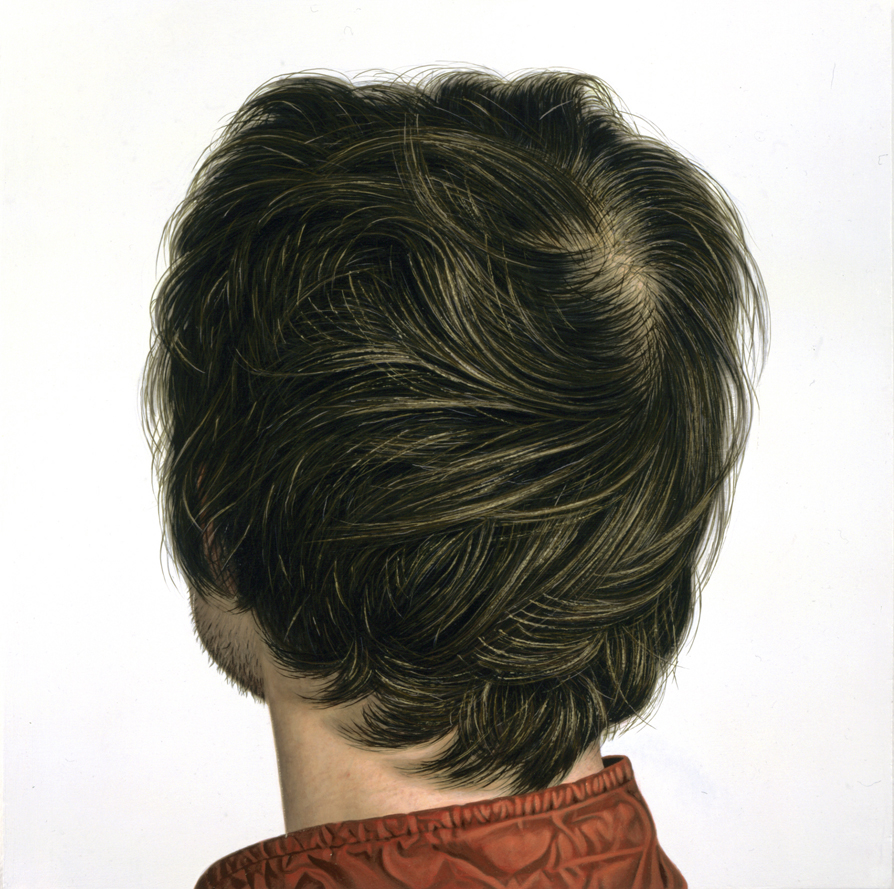

Witness Untitled #4, in comparison to Wyeth’s Farm Road. The artists’ works are unified, not only by the treatment of the hair, but also by the figure’s placement – each sitter has turned his/her back to the viewer. The backward-facing figure is a recurring theme in Funk’s work, and it establishes the aloof tone for which he strives. Funk’s sitters deny us the reward of our glance; they’re the polar opposite of, say, Manet’s Olympia, with her piercing stare and all of the (legitimate) “male gaze” feminist baggage associated with portraits of women painted by men. Funk smartly refuses to engage in this argument, instead choosing to paint only men, and in a clinical style that drains the sitters of emotion, thereby leaving viewers to make a similarly dispassionate choice: either to turn their backs on the work and walk away, or to formulate a formal rather than emotional dialogue with each piece.

______________________________________________________

Funk’s sitters face backward, denying us the reward of our glance. Actually, I think “gaze” iteself becomes irrelevant in most of the images — these aren’t portraits, they’re “non-objective” abstractions.

______________________________________________________

Rochester Art Center’s chief curator, Kris Douglas, likens the work to that of Vermeer, especially in its “compelling depiction of light” and the “motionless quiet… the antithesis of a portrait, turning purely reflexive, an ‘inner’ versus ‘outer’ gaze.”

Actually, I think the gaze, whether “inner” or “outer,” becomes irrelevant in most of the images, particularly in paintings like Untitled #21. Once we deny the fact that these are portraits, Funk’s paintings metamorphose into “non-objective” abstractions. Seen that way, he’s effectively remaking early Renaissance portraiture after abstract expressionism — creating painting that is post-minimalist in tone.

Funk doesn’t want us to know these people. He leaves each painting untitled. Rather, his focus seems to be on the power that abstract painting, itself, still holds over the viewer. Such work can move us ineffably, encouraging renewed attention to life’s smallest details. With their eyes closed and their backs turned, the figures in Funk’s portraits are easy to objectify, dehumanize, and then, in turn, to appreciate more formally. Consequently, these human abstractions offer relief from the modern ailments of “too little time” and “too much information.”

This overall effect is aided by the astounding clarity with which the exhibition is installed by curator Kris Douglas: the viewer is introduced to Funk’s work by way of Untitled #3, the sole portrait where the sitter’s eyes are open. It’s as if we’re being prompted to open our own eyes, to witness what’s in front of us, to focus on the visual, abstract profundity of the coming work. The ample space given to each portrait fuels the paintings’ power, oxygenating each piece, allowing the viewer space to take in each one fully: the 13.5″ x 13.5″ Untitled #5 is allotted a 40-foot by 16-foot wall all to itself.

This installation is quite unlike, say, the classical salon-style hanging of portraits, or the slim space accorded past master portraits at the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts or the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for that matter. While the look of such presentation appears rather frigid at first, it’s nevertheless appropriate, especially given the show’s subject matter and tone. The austere white backgrounds of the paintings coalesce with the RAC’s tall, white walls. Funk’s sitters, shrouded in Gortex and nylon winter jackets are, in a sense, freezing in the snow-white arena of the museum.

One could criticize the Canadian artist’s lack of ethnic diversity in his sitters. Yet, if depersonalization is the aim, the uniformly white male sitters allow the portraits to easily morph into the aforementioned non-objective/abstract territory. If a more diverse array of sitters were introduced into his oeuvre, their distinctive features would generate an individuated energy within the paintings, something Funk is clearly trying to avoid.

In fact, Funk evades narrative and character at all costs, and this is not to the works’ detriment. The formal intelligence in the painting imparts a kind of serenity, something only discovered when communing silently with works of art this refined. It is a mindlessness worthy of pursuit and is, in my experience, certainly not easy to cultivate.

Even so, as Lao Tzu says in the Tao Te Ching, “The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step.” So, go. Visit the Rochester Art Center this summer. Step in from the heat, and savor the calming chill and silent quietude of the work of Karel Funk. And don’t forget to bring a coat.

*****

Exhibition details:

Karel Funk will be on view in the Rochester Art Center’s Onofrio Gallery in Rochester, Minnesota through August 30. Visit the museum’s website for gallery hours, directions, and addition exhibition background information.

About the author: Originally from South Dakota, Minnesota artist Ruben Nusz was raised by cowboys and later graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Minnesota. In 2003 Nusz directed a feature-length documentary that toured the festival circuit. He has exhibited mixed-media works at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, Rochester Art Center, Rosalux Gallery, Umber Studios and the Hopkins Center for the Arts. He is one of the co-founders of SELLOUT Gallery, an artist-run space devoted to the exhibition of work by emerging and mid-career artists as well as independent curators.