Experiments in Motion

Dance writer Lightsey Darst offers her thoughts on James Sewell Ballet's winter performance, "Ballet Works Project" at the Southern. It's an exploration, she says, "in which what to move, how, and why are all up for debate."

AN EXPERIMENTAL TONE SETS JAMES SEWELL BALLET’S winter concert, the Ballet Works Project, apart from the rest of JSB’s season. A smaller stage (the intimate Southern, not the wide O’Shaughnessy), lower-budget costumes, and a variety of choreographers — Hijack (Kristin Van Loon and Arwen Wilder), Shannon Christie, and Nic Lincoln, in addition to James Sewell — all give the impression you’ve been invited to a workshop in which what to move, how, and why are all up for debate.

What to move? How about the Shubert Theater? For its soundtrack, Hijack’s At best steals a History Channel special on the great move, complete with a hype-happy announcer who makes the theater’s move sound like Godzilla descending on Hennepin Avenue. I couldn’t help but overhear Wilder reporting that a friend took the soundtrack to signify that dance is as absurd as a theater rolling down the street. Clever — I wish I’d thought of that. But I didn’t see absurdity in the choice, rather exploration. Penelope Freeh and Sally Rousse, veterans of po-mo ballet, zip through their moves with keen precision and a deadpan intensity that’s sometimes scary, as Freeh switches tracks with razor sharpness, sometimes silly, as Rousse jerkily jacks one elbow up and peers straight-faced through the opening. When those two are on stage, your eye can’t help but follow their expertise. But what I remember more is Hijack’s attention to the dancers they’re less familiar with. Hmm, Cory Goei doesn’t look half bad in a dress, Van Loon and Wilder seem to say to themselves — can he make small movements look like big ones, can he make a quiet exit in a corner seem like a moral event? (Yes, he can.) Or, Eve Schulte luxuriates in lyrical passages; can she apply the same tenderness to un-balletic steps? (Yes, she can.) Experiment dominates. Van Loon and Wilder give the dancers the security of a familiar phrase (tombé pas de bourrée glissade grand jeté, a gliding series of steps culminating in a split leap — trust me, if you’ve seen ballet, you’ve seen it); then they turn it this way and that, as if asking the dancers to reconsider what this step might be. Can it be a question? a reflex? a way to sound out the acoustics? a sneeze? The achievements here, when they come — not everything looks quite right — belong to the dancers, more so than to the choreography.

Hijack’s At best, relationships are marginal, which follows directly from At best, is an entirely different work, more focused on how than what. Originally created for Van Loon and Wilder themselves, and now transposed onto the pointe-clad feet of Freeh and Rousse, this work is not playful and ephemeral but assured, hard-wired to the gut. At breakneck pace, Freeh and Rousse barrel through needle footwork and ripping slips, from peak to floor in the most interesting pointe work I’ve seen in a while. In unison, but at odd angles to each other and the audience, their venom/fury/love aimed offstage half the time, Freeh and Rousse read as opposites, a self and her suddenly conscious shadow, a personal history and its long-buried, now-unearthed negative. The soundtrack of semi-gothic fantasies about small-town life (excerpts from Richard Hugo’s quirky masterwork on poetic inspiration, The Triggering Town) only heightens the sense of disaster at the brink, of matter and antimatter about to collide. “Romance and violence,” the voiceover says, as Freeh and Rousse lie down and click off their nightlights; it’s only one of the oppositions this fierce work radiates.

________________________________________________________

In Dance Forms — Sewell’s latest stab at a longtime fascination with systems for dance movement — he’s after a method to express and direct the forms of dance the way notation does music, something which, maybe, might lead to new ways for thinking of dance.

________________________________________________________

The question “why move?” is up for debate in James Sewell’s two pieces. Dance Forms is Sewell’s latest stab at a longtime fascination with systems for dance movement. He’s after a system to express and direct the forms of dance the way notation does music — perhaps along the lines of Synchronous Objects , William Forsythe’s collaboration with Ohio State University — and leading to, maybe, new ways for thinking of dance. Here, Sewell invents a movement score broad enough to describe steps in classical ballet, modern dance, and even pedestrian movement, then he sends out various groups to interpret the score to different pieces of music, with different facings. You can watch how the score plays out in the various modes, you can enjoy the coincidences between them — but it’s hard not to feel that, despite the best efforts of the dancers, the dance itself is a little unloved, a bit of a byproduct. The garishly costumed classical ballet comes off especially badly; a shred of Don Quixote in a corner, with no perceptible relation to the music and no on-stage support for its aesthetic universe, makes no sense. But it’s an experiment. Who knows what Sewell will use it for?

Sewell’s other piece, Embodied Movement, is a collaboration with therapeutic movement guru Shannon Christie, and it’s expressly a therapeutic piece. Why move? To heal. To get there, Embodied Movement works through three chakras, a suite of sonic vibrations, and a rainbow of colors (cast on the dancers’ white tanktops and bellbottoms). Altogether, it’s like watching a revival, séance, rave, exorcism, spirit possession, etc. — and, as usual, I’d rather feel it than see it.

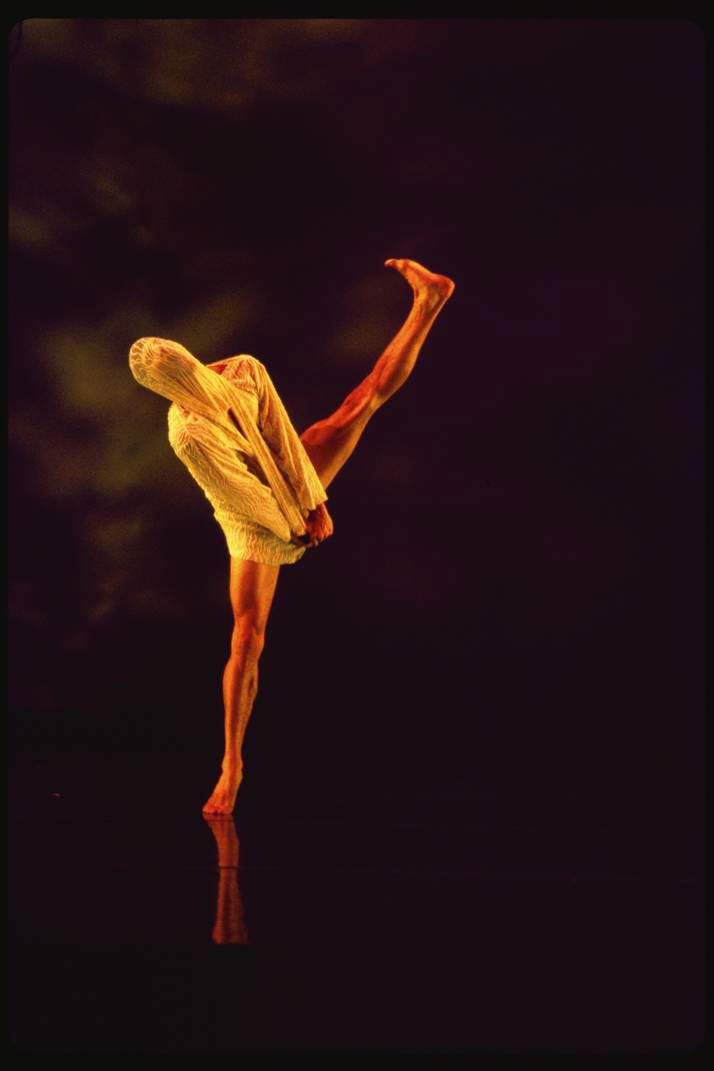

Nic Lincoln‘s Unraveling What Binds is not as experimental as the other pieces in this concert — at least, not at the conceptual level. Unraveling is a tad predictable (of course, the stuffy people in the monkey suits will eventually free themselves and undress) and slightly too long. But on the local level and at his best, Lincoln holds every possibility in his hand. In a quiet spot in Mary Ellen Childs‘s atmospheric music, Penelope Freeh plinks the floor with one hand, everything she isn’t doing peeling away to the sides like the Red Sea splitting. Then, she rises. Here more than in anything else I’ve seen from this emerging ballet choreographer, Lincoln catches the magic of making each moment’s decision matter. At times, his dance unfolds with the strange yet irresistible logic of a Rube Goldberg, each step bringing the next into being. This incandescent Unraveling brings the experimentation back to where it must always begin: the cellular level.

________________________________________________________

Noted performance details:

James Sewell Ballet’s winter performance, Ballet Works Project, was on stage at the Southern Theater in Minneapolis February 4 – 7.

James Sewell Ballet will also be hosting a benefit February 13, Romance Dance – an evening of dance performances and music by the David Mendenhall Quartet, in addition to dinner & dessert, a raffle and both a silent and live auction in support of the company. Find details and ticket information about the Romance Dance benefit for JSB here.

________________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl will be published by Coffee House Press in April 2010; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She hosts the writing salon, “The Works.”