EXCHANGE: Amy Rice and Marya Hornbacher in conversation about art and the disordered mind (Part Two)

The second installment of a dialogue between Amy Rice, acclaimed painter and Spectrum Artworks Director, and Marya Hornbacher, critically hailed author of the forthcoming memoir,"Madness: A Life," on the interplay between art and the disordered mind.

The exchange we began last week, between visual artist Amy Rice and writer Marya Hornbacher on the tangled relationships between art and the disordered mind, continues below:

________________________________________

From: Amy Rice

Sent: Thursday, November 29

To: Susannah Schouweiler; Marya Hornbacher

Dear Marya,

I have carried your last correspondence with me and pulled it out to read over coffee, while waiting for paint to dry, laundry to wash. You’ve given me a lot to think about.

RE the questions initially posed to us by Susannah:

To what extent, in your mind, do the effects of mental illness or upset actually spur creativity? Do you think there are circumstances where these less trod paths of mind, those that upset and disturb especially, can be fruitful and productive rather than pathological and hurtful? Or is the pain of mental illness a necessary part of its fruitfulness? Is a “peaceful” mind, in that context, really a desirable goal?

These questions have become, during the course of our dialogue, the fundamental questions we ask about any artists, about any art. Why do we create? Why are other people even interested in what we create? How do our identities and our experiences shape our work; and how do our identities and our experiences shape how others perceive what we create?

The point you made about people being interested in the experience of mental illness in way similar to the way in which one might be interested in learning about someone’s travels to Indonesia really struck me. The idea comforts me, in a way, because it is so benign.

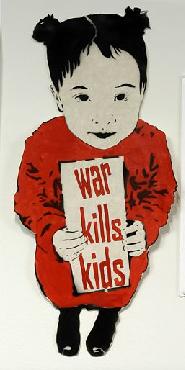

I spend a lot of energy getting the “artists first” message out there. I am easily rubbed the wrong way by someone attempting to view the work of artists living with a mental illness as, well, the work of artists living with mental illness. (I say this even as I curate a new show of artists living with mental illness in an attempt to begin dialogue and break down stigma, to build understanding, blah, blah blah….)

I believe in the power of art to change attitudes and perceptions, but that whole identity question—be it “women’s art” or “immigrant art,” or “African American art”—sometimes muddles up the message, because it changes the meaning of the work in the eye of the viewer, gives unfair attributes, makes things political that are only pretty.

I think you are right, though; many people are very interested in the experience of mental illness, fascinated with it because it is so foreign, but still never that far from home. If a viewer is aware an artist has a mental illness, it will certainly shape how they view their art. In fact, they may presume the art to be about their mental illness, regardless of the actual subject or context. But, what if they also knew that artist was a lesbian and. say, Muslim, and that she lost her Mother at an early age and has a dog she loves? It’s complicated that what we know about an artist really shapes how we perceive their art.

I read an interesting article about a show in California that paired well-established, contemporary abstract artists in a gallery setting with the work of artists, all of whom have serious developmental disabilities, who make art in a day treatment setting. None of the work was tagged, so the viewer was left to play “guess who’s retarded.” I know that was not the explicit point of the show, but I can’t imagine that the viewer experience went any other way. It was a good example of how perceived identity shapes how we view art.

People tend to think I am an Asian artist. (Amy Rice? Really?) I have had people end up really disappointed that I am not. I’m not sure why, but knowing that I am really a chubby, middle-aged white woman makes my art somewhat less appealing to certain types of folks.

I guess where I am going with this is, for many people living with a mental illness, their disease becomes a part of their identity, either by their own choosing or through societal forces. For many visual artists, this myth of the link between madness and genius we’ve talked about can even be used as a door to opportunity if played correctly (and I am not making any judgments here). Sometimes those “art and disability” shows (and the Twin Cities has quite a few of them) are a good foot in the door. Maybe it just perpetuates the myth or maybe we’re breaking down stigma. Or, maybe we’re just giving the masses a peek into a different world; perhaps that is just as benign as hearing about someone’s trip to Indonesia.

Oh my. That’s all I’ve got at the moment.

–Amy

________________________________________

From: Marya Hornbacher

Sent: Friday, November 30

To: Amy Rice; Susannah Schouweiler

Hi Amy and Susannah,

I like the question of how people identify artists and their artwork: how does that identification relate to, influence, or separate their art from one group and then link it to another? Mentally ill art, or mentally ill artists, or art that is made by mentally ill people, or art that a mentally ill person makes…

For myself, I have to go with that last one, and even that feels really weird. My writing is also writing that a short woman writes. No one goes around talking about the short person school, or wonders if the “perspective” of the short person’s “world” is different than it is for someone higher up. In fact, it is. To me, everything looks tall. Perhaps that is evident in my writing. Of course, if I wrote a book about shortness, and the short experience, it would be easier for the reader to tell that I was short, and maybe that would make them wonder whether my shortness contributes to, helps, or hinders my creative drive. If they would see in my writing the great frustration of never being able to reach my cupboards, the defeating need to daily climb onto the counter, the oppressive, never-ending search for pants.

There are aspects of identity, experience, history, and context that are vastly more important, more significant to the reader or viewer, that may or may not contribute to the reader/viewer’s understanding of the world, or that may specify “that” world as separate from the “rest of” the world. And those aspects of identity may be worth exploring for a closer understanding, either of that artist’s work or of the place from which they create. There are aspects of community that give rise to a desire to join that community and be a part of it, in pride, in anger, in an admixture of anger and joy. One needs an origin, and one needs to create a narrative of that genesis and what it becomes, in the person and the community and the work. We need to create, for ourselves, a place in history; and we need to bring that history to those who know it and those who do not. Some art tries to be a voice. Some art tries to speak for a group. Sometimes it works and is valuable. I myself do not write as a voice, for the world. I write for a reader. That is all.

The question of whether art generated by a mind that is different from the “average” mind is, itself, different, is not irrelevant. Some people feel that “the mentally ill” are a group and consist as an origin; most of those people are not mentally ill. And there are mentally ill people who find comfort in being a part of such a group; it gives them a badly-needed place where they are not, as their minds try to make them, utterly alone, and a place where they can feel the world does not mock, imitate, glorify, or denigrate them as symbols of deviance, rather than treating them simply as people or as artists.

It is true that “the” experience of being mentally ill leads to a life that is particular in some ways. As with all questions of art and identity, there is a way in which that identity is expressed as unique; a way in which that identity is expressed in the attempt to join the larger world from which we (“we”?) are sometimes isolated and removed. We are always (the larger “we”) trying to both separate ourselves from the mass of humanity and, at the same time, desperate to join it. People are lonely and hungry for meaning. To find this, we turn to art. In art, we find individual identities if they state themselves and if we look. In art, we also find ourselves.

I’VE ALWAYS HAD MIXED FEELINGS ABOUT THE DESIRE TO LINK ONE’S WORK TO AN “IDENTITY” GROUP, and about how the viewer also wants to do that to the work they see. I think that there are a couple of things at play here: the artist’s very real identification with a community or origin or any group, and her awareness and desire to express that origin and sense of identity; and the viewer’s desire to make the work they view understandable to themselves, to give themselves a context in which to see the work. We always see work in context; it doesn’t exist unto itself, and if it tried to do so, it would alienate itself from our comprehension and from any possibility of meaning. All work exists within a history, a period, an artistic context. In that sense, I think it’s not strange, or necessarily problematic, to create work from a place of identity, and to want the work to be seen within that context. Similarly, I don’t think I can ask a reader or a viewer to see my work as totally divorced from the world in which it and I originate.

I tend to draw back from group identification on any large scale. There are things about art or writing by women that specify it as women’s work (interesting); I think in some cases, in some eras, this is a voicing of a place or group that is useful in understanding it and making it visible to the larger world, and also acts as a point of collectivity to women readers or viewers. But this identification as “women’s art” also over-specifies it and removes it from the context of artistic history, placing it instead in other histories. It belongs in those histories. But I persist in believing that art belongs primarily in the history of art—which is, to me, a critical history of culture and of the world.

I have recently written an essay where I talk about the fact that, at the end of the day, I will always be what they used to call a “lady writer.” There are certain gut-level beliefs that still hold when people view writing by women, even though they are rarely explicit or even identified within the reader. In the essay, I riff on the hilarious term “young masters,” which is used to specify a small group of men writing about a very specific subject in a very specific style. I love the idea of young masters. I love the idea that a bunch of white kids sitting around gazing at their navels in a very hip and ironic way are young masters; they are an interesting corollary to the Old Masters, like Vermeer. These young masters speak from a place as specific as any other group; but their place is considered to be the one from which the next generation of “real” literature can and should arise.

Frankly, I like these writers a lot. They’re very good. But they’re by no means the only masters writing. Toni Morrison is the master. She is not a young bespectacled nerd boy from Brooklyn. And she does not write only as an African American, or as a woman; she writes as a master, about subjects that reflect on African American history, women’s lives in that history and in the history of America, and that shed an incredible light on a culture and a period that precious few people of any race or gender or identity understand. She sheds this light because this is her subject. She sheds it with the clarity she does because she is a master. Her work is part of the historical evolution of great literature. Great literature is no longer specified by gender or race. It has been. Toni Morrison has changed that. If she had been writing solely as an identity, and not as a great writer, she could not have shed that light. She would not have the authority she has without her specifics. But she would not have the authority she has if those were all she had. She does not merely have identity. Morrison has vision. Without that, her work would not reach the world.

THERE HAVE BEEN DOZENS OF BOOKS BY WOMEN who write about the need for that specificity, books that state, accurately, that women’s “voices” have been heard less or differently than men’s, and that their stories have not been told. I don’t disagree with this, and at an earlier point in my career it was very important to me to place myself as a woman writer, a writer whose work was specifically feminine or female, and whose work was specifically the telling of a woman’s story or a story as seen through a woman’s eyes. It isn’t that I no longer think that’s important, the fact that I’m a woman; but I don’t see it as the primary feature or origin of my writing, and there are stories I tell which are not about that fact and do not examine it. I frequently teach a class on modern novels by women (modern as in the early 20th century period); this isn’t because I’m enraged that these women or their stories are being squelched, or because they are different in quality or intent than men’s novels of the same period; I teach them because there are a lot of really good ones, enough for a class of their own, and because they are of that period, they do represent a significant shift in a) the stories that were being told by novels at that time, and b) the way novels being written at all, a shift that influenced how novels were written thereafter. It is important that they be specified, because they represent an emerging body of work and a particular subject; so does surrealism, in the same period, which I have probably a more comprehensive knowledge of than the first. The surrealists were also very intent upon voicing and specifying their own identity, as representative of a particular and “new” type of thinking, writing, painting, and living, a type that emerged in that period because of all the periods that preceded it. Identity plays a role in the development of any emerging school. It plays a role because the people working from it believe it they have something new to say—not something new to say about themselves, but about the world. This world is mediated through their eyes, yes; but they are not the singular point.

When I view work by an African American artist who I know is African American, I sometimes see that work in a larger context, as informing me about a world, a history, a culture, and the artist’s individual interpretation of her subject. I do not immediately see this; I do so if the subject is explicitly intended to reflect on that context, and if the artist herself has identified the work as generated from a place of identification with that group. I don’t tend to see a still life by an African American, of, say, fruit and a vase, as an African American still life; I see it as a still life, and place it in the context of still lives. Kara Walker takes up subjects that intentionally reflect on African American lives; this I see as Kara Walker reflecting on those lives and that history, bringing to bear and working from an experience as an African American person, not as Kara Walker stating herself and making quotes “African American art.” The term “experience” kills me—as if there is an African American “experience,” a women’s “experience,” a lesbian “experience,” a mentally ill “experience,” or that any group of people has a single experience at all, or creates from within that singular and easily specified experience. Walker is not limited by her African American heritage. It gives her authority on that subject. If that was all she wanted to say, and all she was trying to represent, it would have no impact on the larger world of humanity. By bringing forward a vision of cultural specificity, she also speaks to the centrality of specific history and culture in the larger fabric of the human world. She is not simply restating that she, Kara Walker, sees through these eyes. She asks the viewer to see with her. Not to agree, or necessarily even understand. But to see. That is how her work connects.

THIS IS WHERE I ARRIVE AT THE QUESTIONS I, MYSELF, HAVE about identifying work as having originated in a mentally ill “experience.” For starters, there are so many mentally ill artists that it would be hard to know where to start identifying that “experience.” My experience as a person has distinct similarities to the experiences of other people who have the same illness I do; insofar as when we are crazy, we are similarly crazy. We also share a range of personality traits and a range of challenges in our lives. We share a tendency to be “creative,” though what that means is more than a little vague. But I don’t identify myself as a writer with a mental illness; the idea that I would startles me. I don’t think often about how my illness actually influences the act of writing; I have never been called a mentally ill journalist, nor had my journalism viewed in the context of other mentally ill journalists’ work. My mental illness affects my journalism as much as it does my novels: it fucks up my schedule badly. What I am aware of, as a person working with a mental illness, is how it limits me. I am aware of the pain of it as a grief and a struggle in my life. Not as a source of inspiration. I don’t see my mental illness as part of my identity. I see it as a fact of my life.

The irony is that I have just written a memoir about my mental illness. How do I do that and not identify my work as mentally ill work, or myself as a mentally ill writer? Sometimes a book is just a book, and a cigar is just a cigar. It is work about having a mental illness. It is indeed written by a person with a mental illness. There also books about birds, written by people who are birdwatchers. They are not called the birdwatching school of writers, or assumed to be entirely conscripted and driven by their birdwatching habit. They are believed to have a subject, about which they know a lot. I am a junkie and a nutcase; I know a lot about addiction and mental illness. I am mostly, however, a writer. I also know a lot about writing, and could write a book about it; I could write a book about some painters, or about San Francisco, or Minnesota. In fact, I have written a book about Minnesota, and I was called a Minnesota writer. Which is fine; it is a fact, but it is only the most salient fact if I am writing about Minnesota. When I write a book about sitting in Florida, miserably, I will be called a Florida writer.

When I look at the work of a mentally ill person, I see the work. I do not examine it to see if I can find the tortured face of the individual person creating it. I feel it first. If it resonates, I look closer. In looking closer, I hope to find a way in which I can connect with and better understand and experience a larger, intricately interconnected world. That the artist has a mental illness means nothing to me in terms of their work, unless they are trying to tell me about mental illness. If they are, I want to know if it speaks to me on that subject and helps me understand it. If they are not, I do not dig around trying to examine their psyche and find its twists and flaws. They do their work well and with vision, or they don’t. When someone reads my book about mental illness, my hope is that they will learn something about it, and find a way to connect to it. Not that they will hear my scream of pain. Not that they will see me ripping away from them, from their world. I hope that they will feel my work speak to them, and step into the world where they live. More than anything, honestly, I want them to read the book and get the satisfaction of having read a good story. The book is a book. I want it to be on its own merit.

By all means identify me by my location, or my gender. Call me a lady writer. But do not, please, go hunting around in my work for evidence that I am not equipped to do my work, or better equipped, or driven by a pain that magically morphs into vision. If a writer has no vision, don’t read her. Her vision may come from her pain, or her joy. Same place from which any other artist works. Same place from which any other person lives.

–Marya

_____________________________________________

About Amy Rice: Amy Rice is a Minneapolis artist whose work is produced using stencils that she designs and cuts herself. Although this method is basically a form of printmaking, she has the freedom to experiment with color, surface texture, and grouping of objects and thus mood and tone, making each piece unique. She has shown her work in galleries throughout the U.S. and in the U.K. Amy is also known for her advocacy role on the behalf of artists living with mental illness. In 2006 she was named “Mental Health Professional of the Year” by The National Association of Mental Illness/Minnesota and was given the “Arts Accessibility Award” by the Minnesota VSA for her role in making the arts more accessible to people with disabilities. Rice draws inspiration for her work from childhood memories, both real and imagined (or just slightly exaggerated with time), the urban community in which she lives, childhood toys, vintage botanical prints, her dog Ella, bicycles, street art, random found objects, collective endeavors that challenge hierarchy, acts of compassion, downright silliness and things with wings.

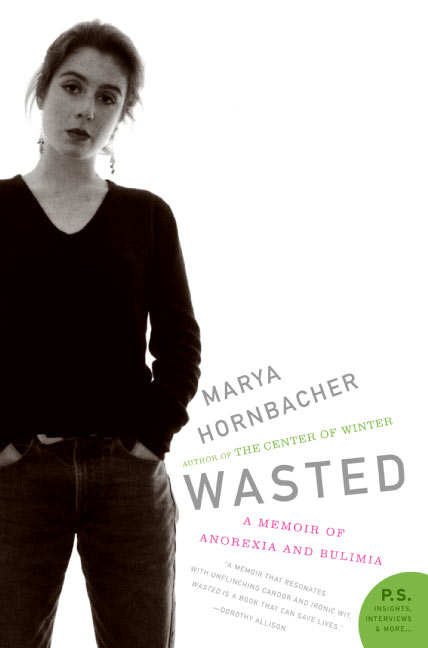

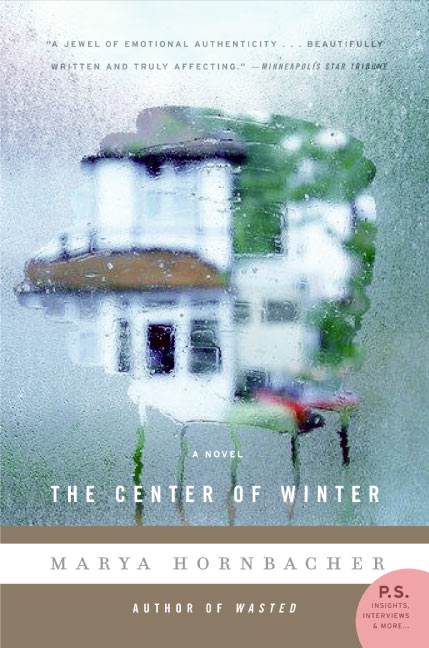

About Marya Hornbacher: Marya Hornbacher is the author of the classic Wasted: A Memoir of Anorexia and Bulimia, the acclaimed novel The Center of Winter, and the forthcoming Madness: A Bipolar Life (Houghton Mifflin, April 2008). She publishes criticism, poetry, and essays in journals and magazines in several countries. She lectures widely on mental illness and writing, and is currently at work on a new novel and a collection of poetry.