EXCHANGE: A dialogue on art and the mind between visual artist Amy Rice and writer Marya Hornbacher

Amy Rice, acclaimed painter and Spectrum Artworks Director, and Marya Hornbacher, critically hailed author of the forthcoming memoir,"Madness: A Life," let us in on a frank dialogue about the connection between an artist's work and state of mind.

_____________________________________________

From: Susannah Schouweiler

Sent: Monday, November 12

To: Amy Rice; Marya Hornbacher

Subject: Art and the Mind

Hi Marya and Amy,

I’m so pleased you’ll be participating in this, the first installment, of a new series of artist-to-artist dialogues we’re launching for mnartists.org!

Marya, you said something recently in a blog entry on your website that really stuck with me:

“Mental illness is many things, difficult and painful to be sure, at times, but also something that can teach a person a great deal about reaching for peace and finding it.”

I also found another of your remarks to be illuminating:

“People vary in what they call people with mental illness: ‘victims,’ ‘sufferers,’ sometimes ‘survivors,’ or the myriad other terms we have for people whose minds are clinically disturbed. (I myself often use crazy, nuts, and batshit, because I am referring to myself, and I can.) Actually, there’s a movement of people who call themselves ‘mental health consumers,’ as opposed to ‘bipolar/depressive/schizophrenic/etc. people’ or ‘the mentally ill.’ I don’t feel at all like a victim; and while, I admit, sometimes I feel like I suffer because of my illness, it is not the primary feeling I have. I think suffering is an occasional part of being alive, and I don’t experience suffering as much as I experience, basically, having a rough patch or a crappy month or something like that. And at times it’s far more extreme than that, and it debilitates me and destroys my capacity to do my work; but what are you going to do besides work with what is? I always want to say to people who say I ‘suffer’ that actually I do pretty well, and that it’s just the way it goes. But ‘survivor’ always feels a little weird to me. Don’t know why, totally. I don’t feel like I’m bravely soldiering through some righteous battle; I feel more like I’m just trying to keep body and soul together like the next guy, and that I do pretty well, considering.”

So my question for you is this:

To what extent, in your minds, do the effects of mental illness actually spur creativity? Do you think there are circumstances where these less trod paths of mind, those that upset and disturb especially, can be fruitful and productive rather than pathological and hurtful? Is the pain of mental illness a necessary part of its fruitfulness? Is a “peaceful” mind, in that context, really a desirable goal?

–Susannah

_____________________________________________

From: Marya Hornbacher

Sent: Tuesday, November 13

To: Amy Rice; Susannah Schouweiler

Subject: RE: Art and the Mind

Amy and Susannah:

I think any mind, any experience, can be fruitful for a creative person. I think creative people and working artists find a great breadth of experience and thought and feeling and perception to bear their own distinct fruit. I do not think, by any measure, that “circumstances…that upset and disturb especially” are more fruitful than any other circumstances, ideas, or desires. I do not think that an altered or disturbed mind bears better, more insightful, or more profound fruit. I absolutely think that people who have seen unusual things, lived through things good or bad or great or hideous, have fruit to bear creatively if they feel a desire to create. Is it art? Sometimes and sometimes not. I also believe that the devastating effects of actually living, day to day, with a mind or mood that is always trying to break free of control, creates a staggering and consistent barrier to the ability to see clearly, produce consistently, and produce work that speaks to someone outside that individual mind.

A peaceful mind is a great gift. Those of us who don’t have them long for them—unless we are still caught up in our own, usually young, self-mythologization and romanticization of our own work, identity, and life.

When I was a complete lunatic with a total inability to function, oh yes!, I was able to generate all manner of totally inconsistent, regularly awful, and occasionally “inspired” work. I was inspired and had a desire to create, but I also had precious little ability to channel that flooding desire/impulse into work that was good or that was developing over time. My mind was not peaceful then. My mind is not peaceful now, either; but I have some peace, and my mind is not out of control, a pure voice, a scream, as it was. And yet, I have a great desire to write—every day, every chapter, essay, letter, poem, article, word. I also have the same desire that anyone else does—to not create for a while, and to watch Law and Order for days, and twiddle my toes.

Inspiration, such as it is, comes and goes. Being crazy doesn’t make me substantially different than anyone else. We aren’t crazy every minute of every day—far from it. I am, regularly, totally uncreative, as are all the artists I know—as well as all the mentally ill artists I know. I don’t have the desire to stagger around drunk and ever so clever, creating and creating wildly. I have deadlines. I have a boring, regular old life: bills and laundry, etc.. And I have to spend a great deal of time trying to keep the monster in its box—so I can work.

IS A PEACEFUL MIND DESIRABLE? I find it so. Does a mind in chemical chaos yearn to create, or have the somehow-special insight to create especially well, or channel some flashing, beautiful, sorrowful, deep and profound insight? That mind might want to create more than the average mind (which exists? Somewhere?). But that mind in mayhem might not be able to work. And there are a whole hell of a lot of mentally stable people who are artistic (or otherwise) geniuses, in the truest sense. Where do they get all that inspiration and creative drive?

All too often, people have some leftover image of the madman genius cutting off his ear and creating the most inspired art in the world; or of the tortured artist, tormented by the colors and spectacular ravishment of his mind. About the ear: personally, I think it was probably not at all helpful in Van Gogh’s paintings, and his suicide certainly interrupted one of the greatest lives in the history of art. And I very much doubt that his work—the skill, the beauty, the grace—originated primarily in the mental condition that made him cut off his ear and end his life. Another drive, more insidious, made him want to destroy what he was, and the mind he couldn’t escape. Inspiration is never enough.

The image and myth of the mad genius allows two things: an automatic assumption that the genesis of a work, a body of work, or a creative mind is somehow without willing source; that the worked-for result of a life of carefully developing skill, context, and craft does not matter or even exist; that, instead, art by the “mad” is purely some kind of savant-like automatic mediation of a Larger Art. Contradicting ourselves, we often operate from the assumption that, in a more modern context, mentally ill people who are creative, or who are working artists and craftsmen, are merely processing their endless, goddamn, always-referenced, pop-psychologized issues.

There is a purpose in creating with the intention or effect of examining one’s own feelings, thoughts, traumas, blocks, concerns. This is a powerful and healing process: exploring the deeply emotional, the part that is prior to analytical or intellectual thought; the process that brings those things forward is a soothing one and can heal. And I believe the opportunity to create this art and nurture this impulse is essential for the people who need it. All artists need to create in that way some of the time; and all people, mind-altered or not, need to express their own demons and pain. They do it healthily or not, and we each find our own voice, or not. Art can be that voice. But the idea that art, per se, for anyone, mentally ill or not, is purely self-focused process, and is therefore either “admirable” or, on the other hand “amateur,” is simple and does not hold.

All our impulses, creative or not, mentally ill or not, are mediated and generated by who we are, how we see, and what we’ve known or can imagine. I have a friend who paints spectacularly well, and sometimes her subject specifically addresses literal questions of mental illness—for example, the creative images she gathered while in the psych ward for a spell. These paintings are not tortured, passionate, disturbed, bloody; they’re actually quite funny, and delightful, and—as all good artwork does—show something to the viewer in a new way. I own one of these paintings: it depicts an orb-like green man with pointed feet juggling cats. This isn’t a hallucination she had. It’s the result of experience, a creative apprehension and meditation on place and context, and a way of interpreting, for the viewer, a strange and separate-from-the unlocked world. A physical world, the psych ward, not Mars. I recognize and laugh at seeing this world in her new way; this is partly because I’ve been to the psych ward, and know its surreal environment and absurd, strange states of mind—but also because it’s a really good painting. She painted it because she is a painter. Not because she’s mad.

AND AS FOR EFFECTS? I can’t work four months out of the year because I’m crazy. I had coffee this morning with a friend, a brilliant musician who hasn’t made new work in two years because her mood disorder is so out of control right now. It’s devastating for her, as it has been for me when I’ve been out of creative commission for two years at a time, as it is for millions of people who have mental illness. Is everyone with mental illness creative? Maybe a slight majority; maybe some people find that their periods of illness give rise to occasionally heightened perception of extreme feeling states and ranges of thought, which can be used to describe in some form the kinds and degrees of human feelings and perceptions that resonate with a wider world. There are far more creative people who don’t have mental illnesses—because there are more people who don’t have mental illnesses. Mental illness, in its effects, is a bitch. Does the having it spark creativity? Sometimes. There are also a whole lot of creative geniuses in science. And aside from Einstein and his fabulous hair and the image of the mad scientist, no one’s imagining that great scientists are necessarily emotionally and mentally divorced from reality, or so deeply feeling and sensitive that they have special inspired insight into the greater meaning of cells.

Does the experience of mental illness create a different context, and sometimes affect the kind of work you do [as an artist]? Do you have a different view from in there, and ways of saying or creating things that someone else doesn’t? Probably you do. If you didn’t think you had something to say, and a new and alive way to say it, and a deep passion for the work and craft, you wouldn’t bother. And that’s why every single artist, mentally ill or not, wants to create: we have a voice, and we want it to it to reach the viewer or listener or reader deeply and personally, and we want that person to speak in turn.

–Marya

_____________________________________________

From: Amy Rice

Sent: Saturday, November 17

To: Marya Hornbacher

Subject: RE: Art and the Mind

Marya,

I was relieved to some extent to discover we are very much on the same page about mental illness and the mad genius mythology that surrounds it. As we begin, I feel I should clarify for our readers that I am a visual artist, but I also manage a small non-profit arts program for adult artists with serious and persistent mental illness (Spectrum ArtWorks). It is not an art therapy program or an art class. It is a physical studio space where artists can meet and make art, build community and work together as advocates to combat the stigma surrounding the disease of mental illness.

One of our greatest collective challenges (and a serious pet peeve) is the idea that, somehow, mental illness—and specifically psychotic disorders—gives one superior artistic talents. We have done a series of public forums on art and identity and it never fails: a member of the audience will argue with the artists (and these are serious artists, who happen to be living with a mental illness) that they have been blessed with “a special light.” Or someone in the audience makes the point, and seriously believes that the gene for schizophrenia is attached to the “gene” for good drawing skills. One of the artists came back with what has to be my favorite line to stem from one of these discussions: “My disease don’t draw dookie”.

Often people respond to this myth-shattering with a statement like, “But isn’t art very therapeutic?” To which we respond with a resounding “YES.” There seems to be this idea that the “mad genius” is the flip side of the “art heals” coin: mental illness makes you artistic, but art is helpful so it all equals out in the end.

As Marya stated so well (and I feel compelled to point out that Marya is a published writer and I am an artist; so please forgive me if I am not nearly as eloquent): metal illness is a tough disease. Yes, it is a disease (not a “special light”); and it’s a disease that can destroy lives and families and make folks simply unable to function day-to-day. While one may find making art relaxing and helpful when their illness is at its worst, every artist I know who lives with a mental illness states that making art is much, much easier when they are healthier.

As we proceed, I want to address these issues in our dialogue here as Amy Rice, “artist,” more than as Amy Rice, “Spectrum ArtWorks Director.” But these first questions really cut to the chase of what we do at the Spectrum ArtWorks Program, and I couldn’t in good conscience take that director’s hat off in my initial response.

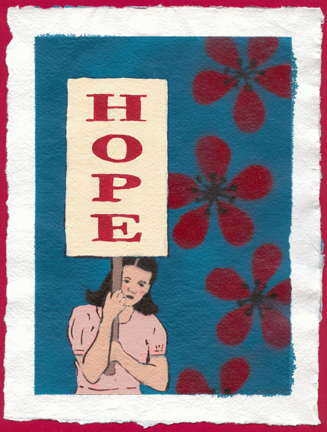

As an artist, I personally take a good deal of inspiration from emotional states that are not peaceful or pleasant. At first look, my work is often perceived as pretty and girly, and maybe as not having much meaning beyond the surface. However, people who are sensitive in the way I am, or people who know me very well can see that there is something I am needing to communicate. And that what I am trying to express is heavy and hard to name. I am trying to work out something akin to homesickness and hopelessness and turn it around into a sense of home and of hope. Even so, I would have rather not have had to experience some of the things that have contributed to the mood and tone of my current work. It’s not an equitable trade-off, I tell you what. I can also say, without doubt, that while I was living through those times of loss and turmoil, I was not able to express what I was experiencing in any way that would have been creative or healing or helpful.

–Amy

________________________________________

From: Marya Hornbacher

Sent: Wednesday, November 21

To: Amy Rice; Susannah Schouweiler

Subject: RE: Art and the Mind

Hi Amy,

I was very interested in what you had to say about how your experience and your work intersect. Your comment that your work, while it does take up visual subjects that resonate with some viewers as peaceful, lovely, comforting, it also comes from a desire to communicate something that is “heavy and hard to name.” I find it enlightening to hear you say that the work stems from some sense of “homesickness and hopelessness.”

Hearing this, learning from the artist in her own words what lies at the emotional genesis of her work, provides insight into the complexities of a piece or body of art. I think that insight greatly enriches the experience of the art. There is always the possibility (probably the necessity) of a divide between where the artist is coming from and where the viewer is. This distance is the tension and beauty of creative work; it is also the tension and beauty and complexity of human expression and relationship. I think this the reason why people both create and view art: to examine that tension, experience it, resolve it if they can, or allow it to fail to resolve.

What you say about trying to turn those heavy things into “a sense of home and hope,” speaks precisely to the distinction between working for oneself, expressing oneself solely to satisfy that need to express, and, on the other hand, attempting to transform one’s own perceptions, experiences, and emotions, into something that the viewer (or reader) can use for themselves, experience for themselves, and discover something about their own experience, thoughts, opinions, ideas, and emotions.

THIS, TO ME, IS WHAT ART SHOULD DO: it should emerge from a deep place in the artist, move through the work, and find its home in the viewer. It is then the viewer’s. It becomes a part of them and a way for them to access a deep place in themselves. What I say is not mine: it is yours. It comes from me, from something I feel or have seen or think about it. But it is for you.

This, to me, is the opposite of what people often assume about art, especially art by people with mental or emotional problems: that is, that it primarily satisfies the artist’s needs. If art did only that, I wouldn’t consider it art. That does not mean that the act of creating would not be healing. And, in fact, it is certainly possible that something beautiful or striking or challenging can come from an artist who is working, at that moment, from and for a need of his or her own. But if I have some kind of extremely amorphous idea of what I think art “is,” then that idea centers on the belief that art is a dialogue. Between you and your viewer, and between me and my reader. We may be writing or drawing or painting (or dancing or acting or composing et al) from a place in ourselves—of course we are—but I think the desire to actually share that work with someone else is based on a desire to reach them, at a personal and interior and deep level.

Artists may be—are—working out our thoughts, emotions, and experiences in what we do. But if we stopped there and did not try to meet the viewer, they would have no need for our work, would take no pleasure in it, and would not get that longed-for frisson (forgive me, I was overexposed to postmodernism in college, never recovered) when they experienced our creative work. We could be doing it just as well by and for ourselves. But we don’t. I have always joked that artists are incredibly arrogant in our conviction that someone wants to hear what we have to say. And maybe they don’t. But I don’t think we would try to reach them if what we really wanted to do was reach ourselves.

You say very clearly that you are trying to express something painful and transform it into something else. I think you’re saying that you feel a desire to create something beyond what you, yourself, have experienced or felt. I think one of the things that can be most fascinating in an artist’s work is the tension between where they are coming from and what they are longing for; between their own darker places and the desire to create, for someone else, some light; between our inarticulate desires and the desire to articulate them. I think this tension can be seen and felt in a great deal of good work.

In many works of great beauty, there is sadness and a pathos that creates a parallel longing in the viewer. Maybe it’s the longing to believe fully in that kind of beauty, or the longing to be able to apprehend beauty on the unobstructed, visceral level that the work captures. There is a reason powerful art makes you cry. It is because you have been met in some way. The artist has expressed something you feel, or have felt, or that you want to feel and can’t. I have no need to express things which are only about me, or which are important only to me. For this, I have a very good therapist.

My desire to create and share work with a larger audience stems from a desire to communicate with them. And I mean with. I am not giving a lecture. I am not singing the song of myself. I am trying to reach them. One can always wonder if one creates because one is lonely, and because one finds the hope of connecting with some nameless you by creating. I don’t suppose that’s absent from some work, and I don’t think it makes the work less interesting or worthwhile. But I believe most people receive or seek out art because they want to be connected with. The artist is trying to give them that connection. I don’t read a book or study a painting primarily because I want to be told how to think or what to feel. I do it because I want to be triggered to think and feel—sometimes in new ways, sometimes in ways that give language to what I did not know I believed. I want that new understanding and perception to make me a broader person, one more able to empathize with and understand people, and so that I can continue to grow—as a thinker, an artist, and as a person kicking around the world.

As an audience member of art myself, I am always interested in the states of mind that contribute to the making of the work. I have an interest in the creative process and in the influences, events, feelings, and thoughts that go into a work or that may inform its style or subject. This interests me as an artist, too. I like to know how other artists work, as I imagine doctors like to hear about how other doctors work. I am also interested art the way some people are interested in physics: it fascinates me, inspires me, delights me, opens out ahead of me toward mystery. I like to hear the stories that are behind a piece of work, and the ideas and impulses that are behind the working.

ABOVE ALL, I’M INTERESTED IN WHAT MAKES PEOPLE PEOPLE. I am a total nerd: I read philosophy for fun, because I like to think about thinking and the way we are human. I find art to be one of the most crystallized expressions of how the mind works and of how the heart does as well. One of the great pleasures of witnessing art and participating in it, for me, is engaging at the intersection of mind, heart, and gut at the point where art emerges, exists, and is shared.

So in the sense that I am also curious about how the mind works, I understand a curiosity about how the disordered mind works. I don’t entirely understand the belief that mental illness or a departure from “usual” states of mind can be somehow more generative, or differently generative, than “normal” states of mind. To me, it doesn’t follow that a disordered mind finds, in its disorder, more truth. I don’t think that good art has to come from devastating pain; some might, but a lot of it doesn’t. I think good art comes from strong feeling, insight, and the ability to articulate these things for the audience in a way that makes them feel or think something more intensely, or in a way they have not felt it or thought it before.

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers make me cry. I have no idea why. I don’t for a moment believe that it was his intolerable suffering that inspired them. I don’t understand why anyone would think his mind (or my mind, or another mentally ill person’s mind) has more or better “insights” into reality, or that he had some kind of special access to artistic truth because he was ill or in pain. I think people who do good artistic work have a way of seeing that is unique, and that that perception, in its uniqueness, speaks to the people who engage with that work.

To the best of my knowledge, the gods have no interest in channeling themselves through me while I am running around town in a gardening coat and three hats. The artists I know who live with mental illness similarly feel that mental illness inhibits both their creativity and their productivity. If my desire to create good work is to communicate—and it is—then I am never more aware of my inability to reach another person than when I am locked in my disordered mind.

AND WHEN I COME DOWN? HAVE I SEEN SPECIAL THINGS? I have seen, sometimes, interesting things that may also be interesting to another person, in the same way that someone who travels to Indonesia has seen things that would be interesting to me. That, too, would be a foreign world to me, and I would want to hear about it because I am curious and interested in how people live, what people think, what things look like, how a place felt.

It’s obvious that I think some of my experiences of what I call madness will be of interest to other people; I’ve written about them twice. The stories of the psych ward, or of psychosis, or of driving a hundred miles per hour because I felt “floaty,” are places where most people haven’t been; and these places are funny, or scary, or surreal. They are these things to me and, when I write about them, I try to give the reader the same feeling I have had, to show them things I’ve seen.

I don’t do it because these things are wounds to me, or because I need to express myself, or because I need to cathart. I do it in great part because it’s a good story, and I do an OK job telling stories. And I do it because, as odd as it sounds, I think people will find a place to connect with what I write. They will see into a world, and in that moment step in. Just as I will see into a world when I read a book about somewhere I have never been, or about a person who has experienced something I have not, or about an opinion I do not share but want to understand. When I look at or experience a powerful piece of art, I will see into a world I do not know, or into one that I recognize on sight but did not know how to describe.

Art makes the familiar strange, and brings the unfamiliar close. It helps us see things anew. It broadens our mind or knowledge as well as the capacity we have to feel.

–Marya

_____________________________________________

Be sure to check back next week for the second and final installment of this provocative, powerful series of letters.

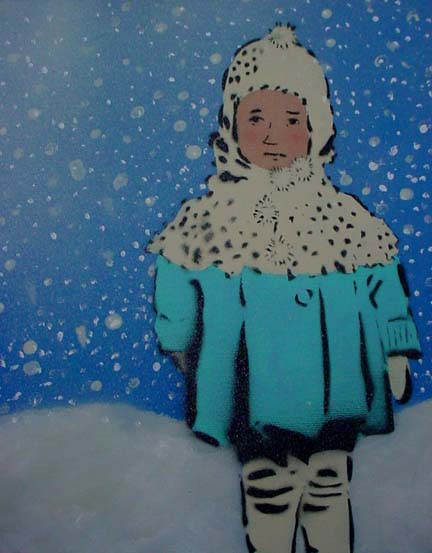

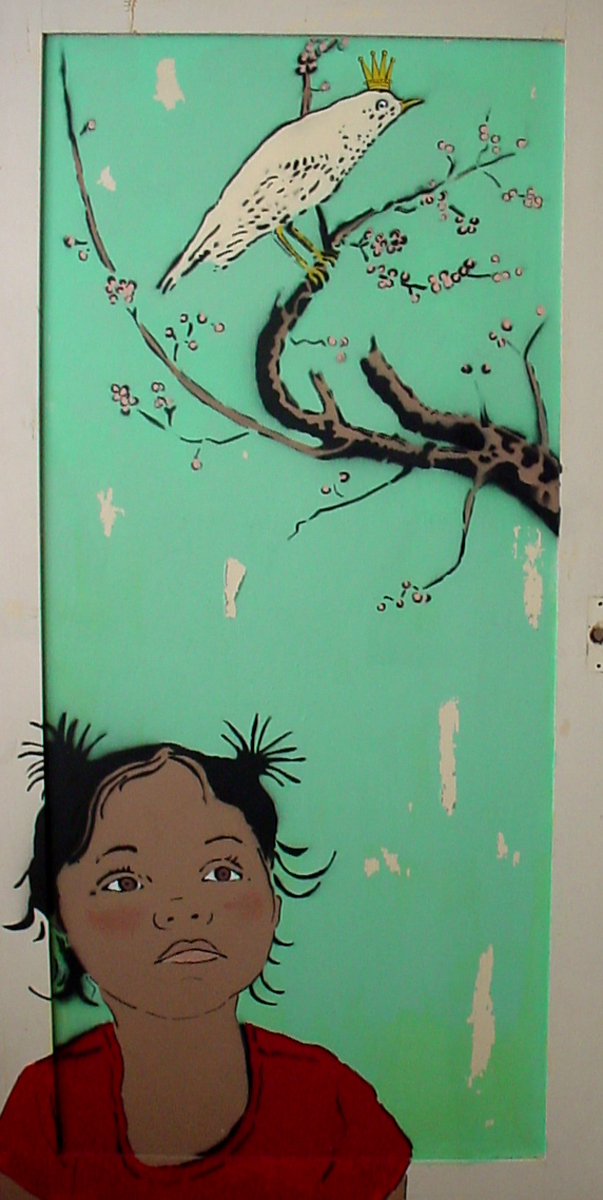

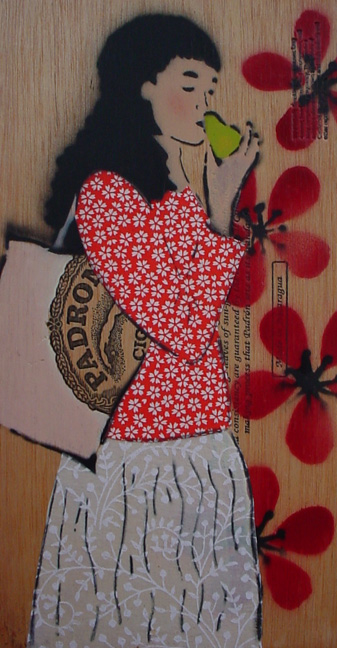

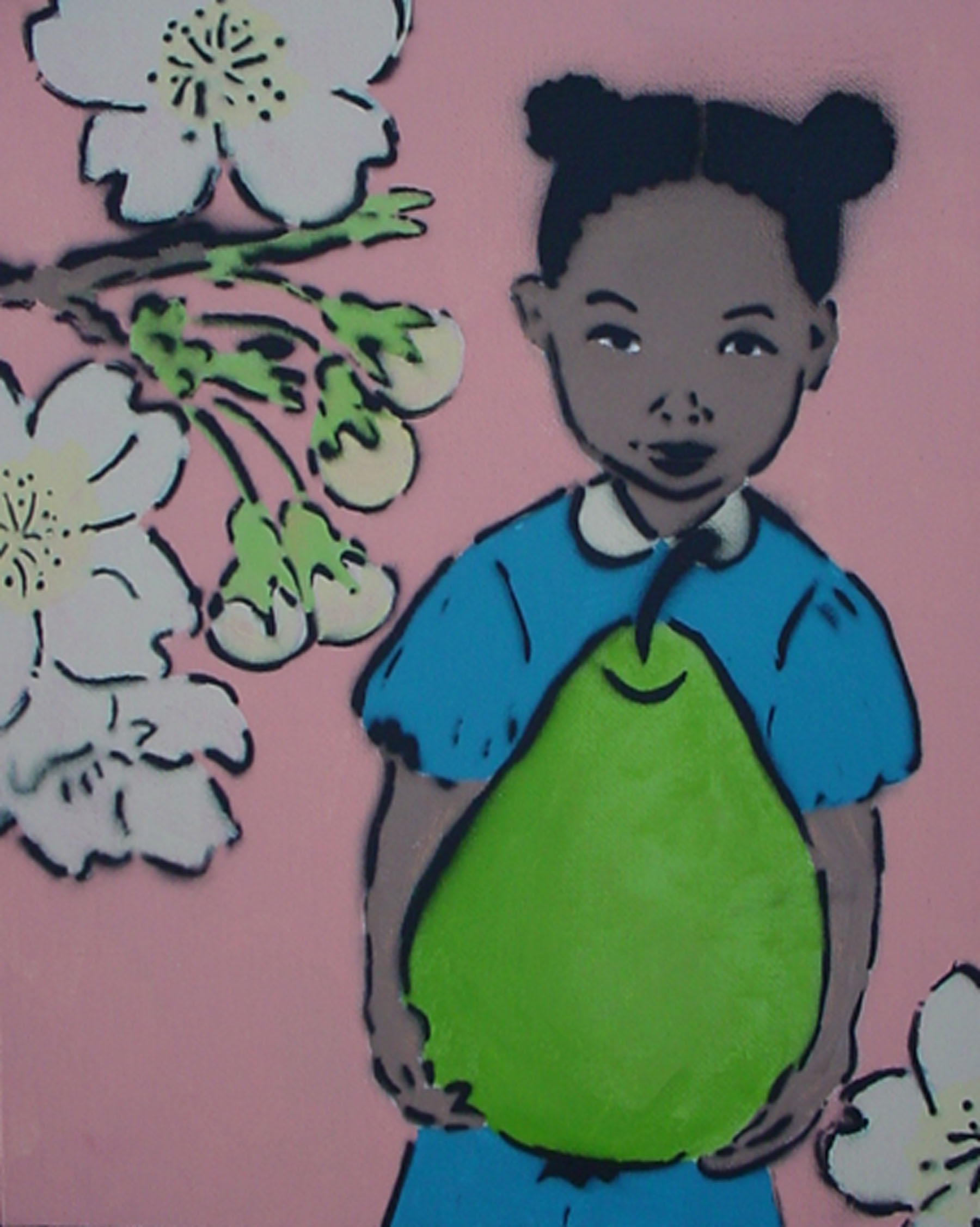

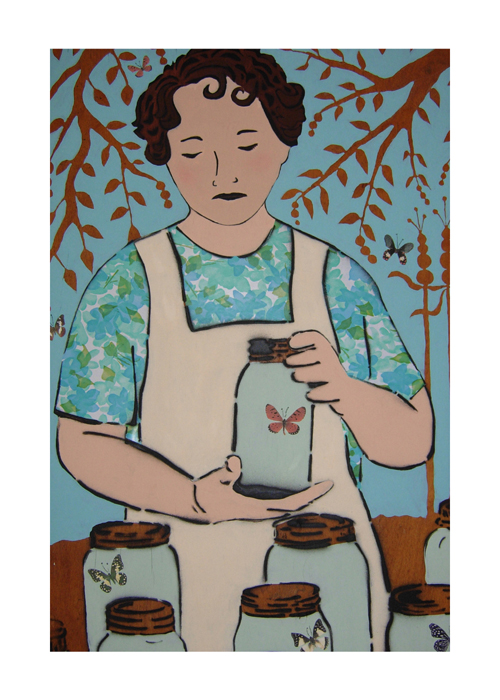

About Amy Rice: Amy Rice is a Minneapolis artist whose work is produced using stencils that she designs and cuts herself. Although this method is basically a form of printmaking, she has the freedom to experiment with color, surface texture, and grouping of objects and thus mood and tone, making each piece unique. She has shown her work in galleries throughout the U.S. and in the U.K. Amy is also known for her advocacy role on the behalf of artists living with mental illness. In 2006 she was named “Mental Health Professional of the Year” by The National Association of Mental Illness/Minnesota and was given the “Arts Accessibility Award” by the Minnesota VSA for her role in making the arts more accessible to people with disabilities. Rice draws inspiration for her work from childhood memories, both real and imagined (or just slightly exaggerated with time), the urban community in which she lives, childhood toys, vintage botanical prints, her dog Ella, bicycles, street art, random found objects, collective endeavors that challenge hierarchy, acts of compassion, downright silliness and things with wings.

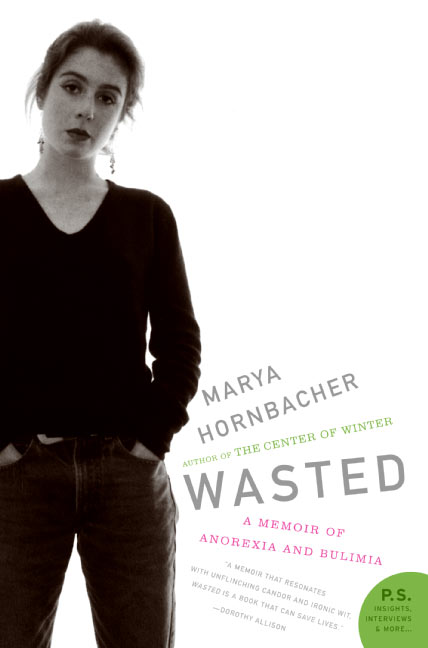

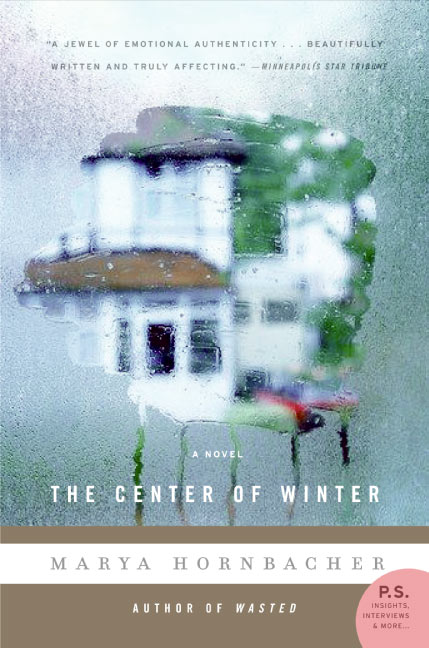

About Marya Hornbacher: Marya Hornbacher is the author of the classic Wasted: A Memoir of Anorexia and Bulimia, the acclaimed novel The Center of Winter, and the forthcoming Madness: A Bipolar Life (Houghton Mifflin, April 2008). She publishes criticism, poetry, and essays in journals and magazines in several countries. She lectures widely on mental illness and writing, and is currently at work on a new novel and a collection of poetry.