Everything and Nothing, All at Once

Ruben Nusz weighs in the ongoing Rob Fischer exhibition, at Franklin Artworks through October 30, calling the artwork "challenging, but wholly worthy" of your attention.

IN 1915, D.W. GRIFFITH PRESENTED HIS CONTROVERSIAL — critics would say racist — silent film, The Birth of a Nation, to a country still licking its wounds after the upheaval of the Civil War. The most profitable silent film in history, Nation incited riots in some cities and was denied release in others, like Minneapolis.

The United States exists today in a deeply partisan, but relatively civil, political respite (irrespective of the 68,000 American troops in Afghanistan); even so, only 145 years have transpired since the American Civil War. Indeed, there is but a fine line separating order and chaos in all aspects of our world: in society, in nature, even within one’s own consciousness. We generate working definitions for these polarities in an attempt to understand and, in some sense, exercise control over them. We aim, with language, to place states of order and dissolution into fixed categories — hot and cold, up and down, ordered and chaotic, sanity and madness– only to see our efforts at making meaning discarded when happenings in our world don’t follow those carefully defined, predictable patterns.

For his second exhibition at Franklin Art Works, Few Landmarks and No Boundaries — a show which marks the 10th anniversary of this steadfast, non-profit gallery space — Minneapolis-born, Brooklyn-based, mixed-media artist Rob Fischer reconstitutes wood, metal, and other urban detritus (e.g. discarded signs, car parts) into a sculptural installation that illustrates the vacillations and tension between the appearance of cohesion and the forces of decay.

When considering entropy, multiple definitions abound; my colleague John Fleischer re-introduced the concept to me in discussing the work of Carlos Degroot. Entropy can be the “tendency for all matter and energy in the universe to evolve to a state of inert uniformity.” Likewise it can be defined as “the inevitable and steady deterioration of a system or a society.” Alternately, entropy may also be the process by which “nature tends from order to disorder in isolated systems.”

Fischer creates order from cast-off materials for his temporary installations and sculptures, and then he deconstructs them, restoring their original disarray. He then resolutely begins the whole process again, recycling parts from old sculptures to create each new work. As in nature, nothing is static in Fischer’s world — objects age, decay, and are reborn as something new. Like a writer who reuses her old poems to fashion alternate pieces by rearranging the words, over the years Fischer has developed a practice that is at once self-contained and expansive, extending into the world at large.

Previous examples of Fischer’s sculptures and installations have been included at exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and PS1; these works involved upturned industrial dumpsters embedded with glass, hybrid flatbed trucks, and a single engine plane with ice shanty add-on. For this exhibition at Franklin, Fischer’s central media appears to be metal junk, abandoned signs, and reused floorboards (from a gymnasium or a previous sculpture). His ever-evolving works prompt the question: What is the true, original source of any material? In the case of the floorboards, is the wood itself the fundamental substrate? Or should you look more deeply, to the cells that give substance to the wood, or to the sunlight that fuels cell growth?

Fischer’s use of space mirrors the expansive visual and conceptual implications of the work; his exhibition extends beyond the main room and into the gargantuan Franklin Art Works performance gallery. Housed in a renovated silent-era movie theater built in 1916, Franklin Art Works was remodeled a decade ago, exposing a number of the distinctive, silent-era features of the building, including a performance space that boasts the “theater’s original, plaster movie screen and proscenia.” Fischer’s exhibition is the first to capitalize on this space, and the supplement doesn’t disappoint.

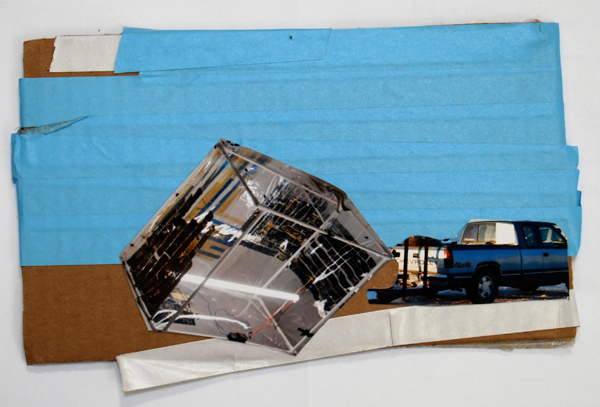

Against the backdrop of Franklin’s decayed, plaster screening space, and projected images of Minnesota’s landscape, Fischer’s sculptures complement the aesthetic of that bygone era in cinema and art by channeling early 20th century Modernism and the sculptures of Robert Rauschenberg, John Chamberlain and Jasper Johns — specifically Johns’ plastic Set elements for ‘Walkaround Time.’

Johns’ set pieces feature elements inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, a seminal work that is as impenetrable as it is profound. Fischer’s re-imagining of Johns’ work is self-conscious, bordering on solipsistic. Screenprinted on his plastic boxes, Fischer uses images of Minnesota prairie grass, Warhol-esque “wanted posters,” and depictions of his own past works, even including some from the current show. Fischer manages to strike a precarious balance in the installation, between art history, site-specificity, and his own personal experiences with art.

With a nod to Rauschenberg’s loose, matte-flat painting style (Rauschenberg used discarded hardware store latex paint), Fischer covers multiple found plywood signs with expressionistic, free-flowing strokes of flat paint. Rather than hang these works, Fischer leans the boards against the gallery walls. It’s not clear whether Fischer stumbled upon these works on the side of the road or simply painted them himself; regardless, the clarity of his vision (part arte povera, part appropriation art, part abstract expressionism, part post-Minimalism) and the continuity amongst these disparate works is astounding. He manages to blend these various styles and moments in Modernism into an amalgamation of forms, history, and experience.

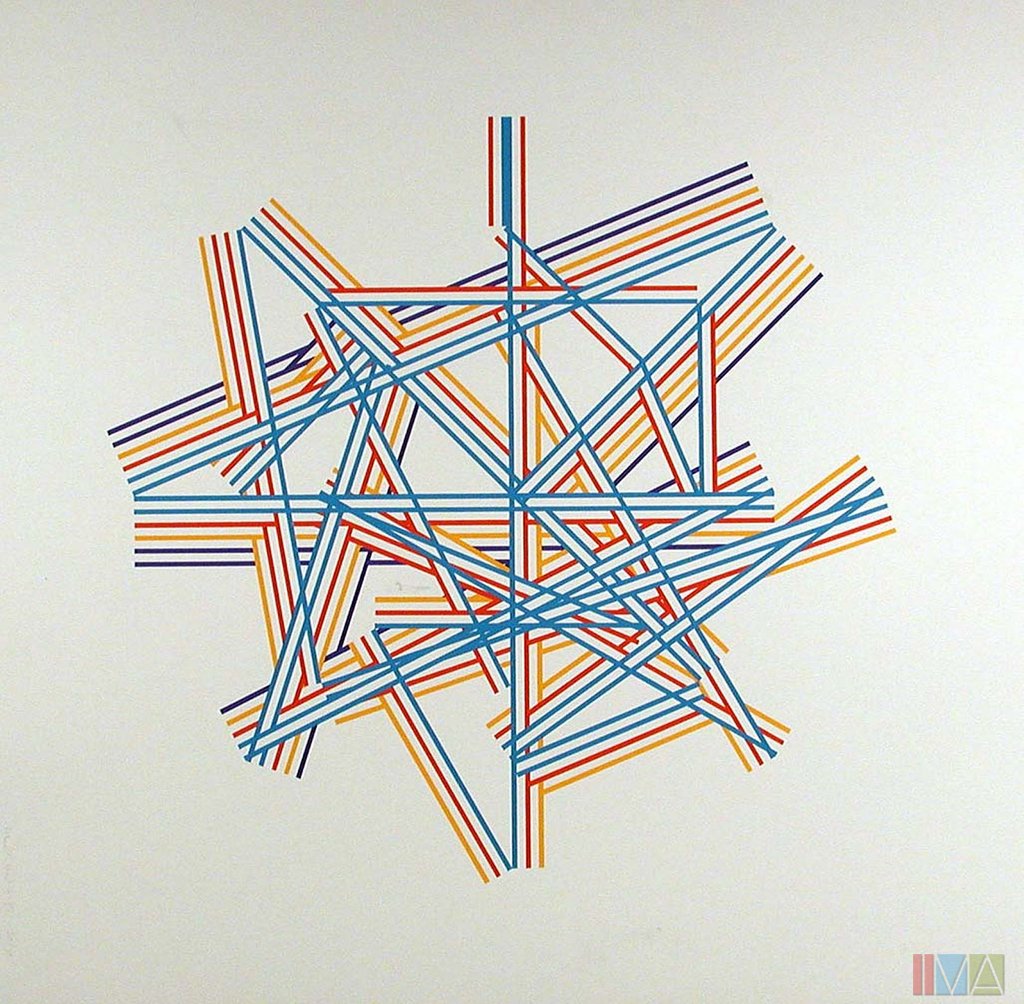

With work spun out into the adjacent performance space, Fischer’s exhibition blends seamlessly with its industrial surroundings. The crumbling plaster movie screen harmonizes with what is the installation’s piece de resistance: a poetic extraction from a reconstituted gymnasium floor, extending like a wooden Carl Andre sculpture, from ground to wall and climbing toward the ceiling, evolving into an interwoven maze of linear wooden forms. Like the neo-Constructivist shapes of Kenneth Martin‘s drawings and paintings — Martin used mathematical formulas and chance as prescriptions for his drawings — Fischer codifies chaos.

______________________________________________________

In Franklin’s cinematic theater space, the scale and scope of Fischer’s project triumphs, underlining a subtextual motif about the American need to consume and to own, but also to flee toward a life unbound by conformity, toward some idealized, apparently more liberated past.

______________________________________________________

This bowling lane for the gods recalls the best of George Morrison’s totems and (to paraphrase Paul Klee‘s description of drawing) takes one’s eyes and imagination for a walk. The sheer scale of the work is intimidating, and made even more so when one considers that the piece will soon be disassembled then, perhaps, reconstituted in future sculptures or simply returned to the junkyard where the boards were originally unearthed. It’s entropy in action.

Nestled between two large concrete slabs, a rather unassuming sunken pond bisects the gallery space. Upon close inspection, one can see that the water has become a magnet for dirt and all sorts of insects. It’s like an Indian tiger trap, where unsuspecting animals might fall into the large puddle while going about their daily routines. Considered in that context, this poky pond could be a post-apocalyptic rat trap for hunger-starved humans — that is, it would be if rats weren’t able to swim (they can).

Fischer’s exhibition title, Few Landmarks and No Boundaries, suggests a narrative of the infinite, open road; but the story in these pieces, at times, seems a little far-fetched and antiseptic in Franklin’s standard exhibition space. Yet in the gallery’s theater, Fischer’s installation seems suddenly plausible; here, his story thrives. Like D.W. Griffith, Fischer gives us a glimpse of the American experience, warts and all. In this cinematic space, the scale and scope of his project triumphs, underlining a subtextual motif about the American need to consume and to own, but also to flee toward a life unbound by conformity, toward some idealized, apparently more liberated past. At some point, maybe we all desire a change of scenery, and to escape from the very lives we’ve willingly made for ourselves. Could this have something to do with a longing for control, or with the empowering agency of free will? Maybe, in the backs of our minds, we fear that the choices we’ve made couldn’t have been made differently given the circumstances.

Clearly, Rob Fischer revels in the tension between the known and the possible. And, armed with the foresight that Fischer’s impressive installation will soon be dismantled and reconstituted, he makes us quite aware of the inexorable cycles of birth, death, and rebirth in our daily lives. Yet, there is a drab gloominess, even fatalism, about Fisher’s work that’s like a harbinger of the coming winter. Regardless of our yearnings otherwise, fall will inevitably dissolve into the long Minnesota winter; and, likewise, spring and summer will return to us again soon enough. All will be well in the world. At least until it isn’t.

______________________________________________________

Related exhibition details:

Rob Fischer: Few Landmarks and No Boundaries will be on view at Franklin Artworks in Minneapolis through October 30. There will be a closing performance and reception, with live music by Dark Dark Dark, at the gallery on October 29, beginning at 7 pm.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from South Dakota, Minnesota artist Ruben Nusz was raised by cowboys and later graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Minnesota. In 2003 Nusz directed a feature-length documentary that toured the festival circuit. He has exhibited mixed-media works at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, Rochester Art Center, Rosalux Gallery, Umber Studios and the Hopkins Center for the Arts. He is one of the co-founders of SELLOUT Gallery, an artist-run space devoted to the exhibition of work by emerging and mid-career artists as well as independent curators.