DANCE: The Momentum Continues

Lightsey Darst assesses two very different "Momentum" performances from the second weekend's line-up of shows--the oblique "La Brea" by Anna Marie Shogren and wildly entertaining "Brown Rocket" by Eddie Oroyan.

WHATS FASCINATING ABOUT MOMENTUM is the variety of visions of performative art that you get to see. Brains, beauty, emotion, whatever your flavor, youll find it here. Is that dance? asked a young male dancer, pointing out one vignette from the Momentum poster hung opposite his ballet class. It doesnt even look like dance! I can only hope he comes to inspect the un-dance for himself. One thing you cant do at a Momentum performance: stay provincial in your ideas about dance and art.

Anna Marie Shogrens La Brea is, presumably, transparent to herin an interview, she calls her work thoroughly, perhaps to a shameful point personalbut from the outside its more riddle and ritual. Not that thats a bad thing. Watch another life from one remove, and you do begin to get a hamster-on-a-wheel effect, while decisions and reversals pile weirdly, like humps of nesting material. A lot of artistic work aims to simplify your view, to bring you inside, but its Shogrens peculiar task to highlight the absurdity while hanging on to the human immediacyto dramatize the oddity of human connection.

_________________________________________________

Watch another life from one remove, and you begin to get a hamster-on-a-wheel effectwhile decisions and reversals pile weirdly, like humps of nesting material.

_________________________________________________

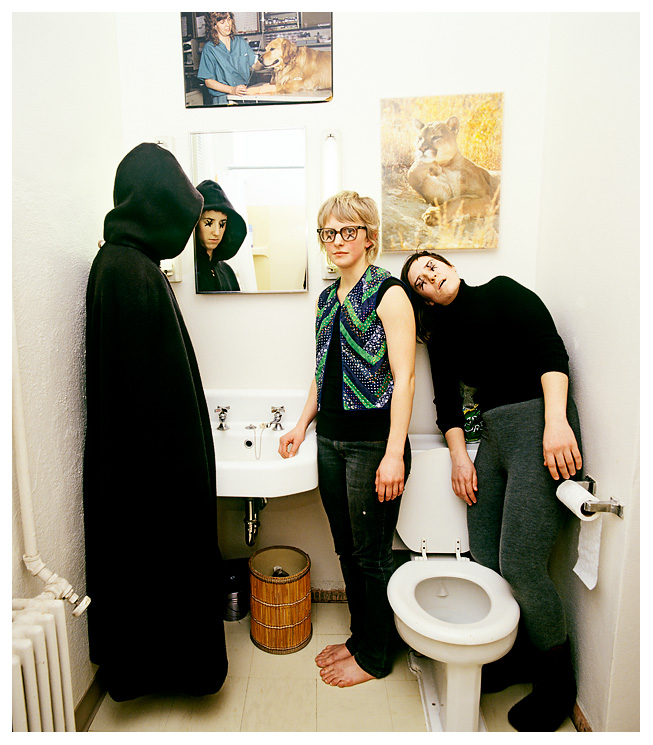

The nest of La Brea is replete with the Shogrenisms her viewers have come to rely on: for example, her awkward-chic thrift store aesthetic, which you can join in by shopping at a laden table in the lobby. You can giggle at her ought-to-know-better ’80s nostalgia, complete with nerdy recreations of movie scenes, advertising faces, and dance steps, as she and her two dancers pony-prance around the stage to Jump (for My Love), filling out the entire song like girls at a bad slumber party. Shogren has a strange power of setting people off suddenly, so that one minute theyre sitting still, quite sober, maybe not even smiling, and the next minute theyre laughing hysterically. This is partly due to the rockin’ ’80s shtick, but even more to her deadpan stares that shift imperceptibly from geek confusion to erotic longing, and which accompany tentative, yet specific gestures. Watching this sort of thing is like watching someone go crazy while shes loading a grocery cart with pudding pops. You start laughing to break the tension, and you keep laughing out of relief that youre not there yet yourself.

Shogren grounds all this referential mugging in a loving care for the fine-grain detail of each movement. A lazy tiptoe walk by one dancer morphs into a series of slo-mo spring-heels for another. When this second dancer turns the tiptoe bounce into a foot flutter that starts in a crouch and rises, losing momentum, to full height, things get really creepy, because this second dancer is garbed as Death, with long black cape and crossed-out eyes.

_________________________________________________

It has the feel of a Hieronymus Bosch obscenity, crossed with Monty Python:

Death farts in our general direction.

_________________________________________________

In the final permutation of this move, Death skitters across the stage on hands and toes, her backside to us, occasionally stopping to bounce and wiggle. This has the feel of a Hieronymus Bosch obscenity, crossed with Monty Python: Death farts in our general direction.

Death does seem to be the central topic of La Brea. In the staticky soundscape, a man reads off a little story about bugs burrowing into his skin, noting the incredible grossness of it. Theres the title, too, and Kristin Abhalters black-painted rendition of the kitschy yet curiously effective mammoth death diorama from La Brea, which hangs at the back of the stage. After the slumber party dance-off, one dancer keels over and another makes a furious pantomime of telephone dialing, sirens, and basic wrongness to the other live girl, who just stares off into space. After a while, the gesturing dancer stops: theres nothing left to do. This makes me think of how little reassuring ritual we have left these days, how theres really nothing to do when people die.

It also reminds me of those terrible ads in which old people fake having fallen over and then deliver lines like Call EMS or Help! Ive fallen and I cant get up with a total lack of conviction. That emptinessthe emptiness which precedes death or that comes after, or the emptiness of fearfills up La Brea. In fact, it fills it up a bit too much. I guess I can appreciate how a really slow fade-out, with nothing else going on, gradually tricked my eyes into mistaking a couple of bare mattresses with a cheap throw over them for the couch of Sardanapalus, but whats that got to do with anything? The conspicuous barrenness at the heart of La Brea seems to go beyond its subject, into the politics of entertainment. Shogren, who has acquired a reputation as a funny girl, doesnt give us much to laugh at or even to look at here. Instead, she casts us back on our own resources. During one particularly long pause, voices mumble audibly but unintelligibly offstage, as if somethings gone wrong. Whats an audience member to do?

Clearly, La Brea is not a fun little ride, even if parts are funny. Instead, watching the performance is an unsettling, disquieting experience. Whether that means Shogrens done well or not so well is up to you.

_________________________________________________

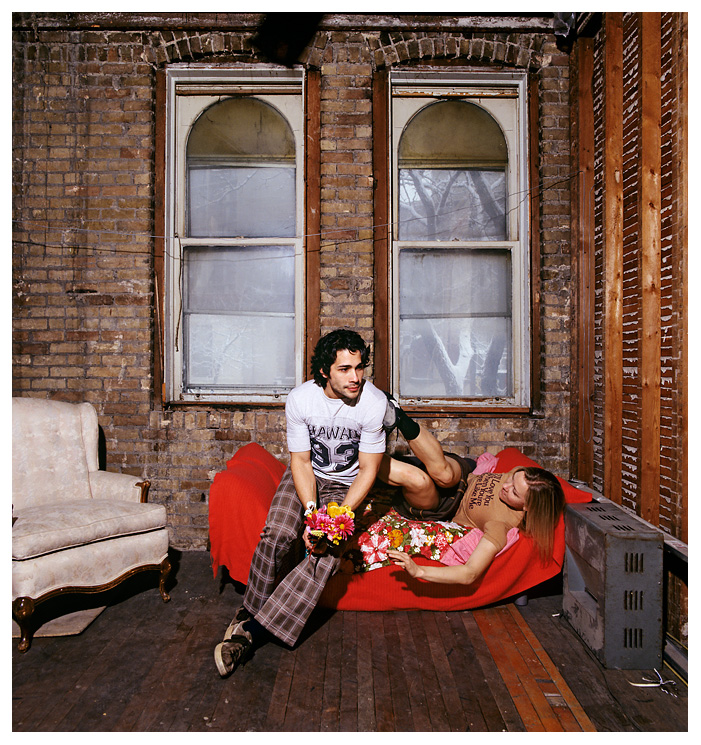

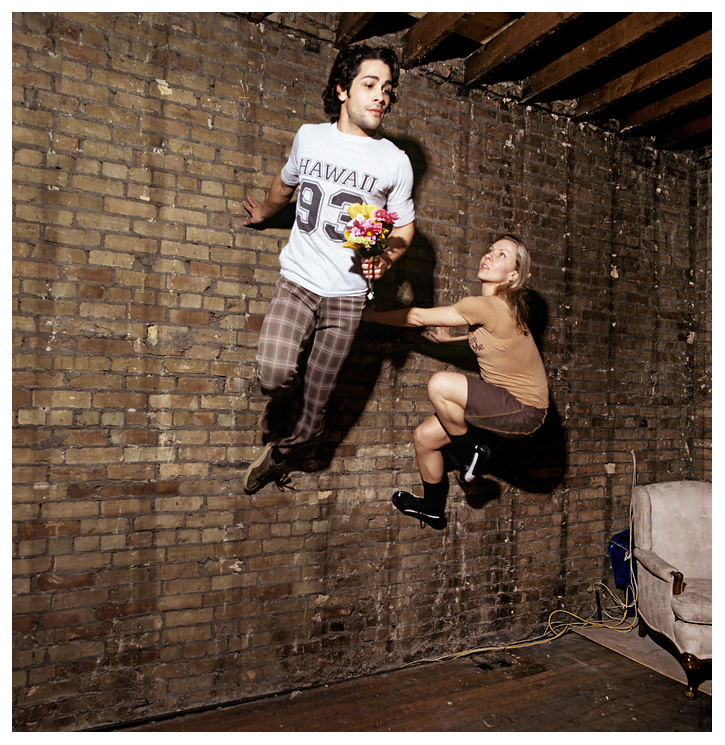

Put Eddie Oroyan and Laura Selle Virtucio in a spaceflying together in gymnastic exuberance, flipping apart in animal fitsand youve already got a spectacle.

Add a four-man pick-up rock band, a raucous set, and a zinging sense of humor, and you have an audience in a lather.

_________________________________________________

And now for something completely different

Eddie Oroyans Brown Rocket (ridiculous title intended) is such a fully-fledged, tightly contained dance drama that its barely recognizable as a Momentum piecethus proving that you never know what to expect at this annual dance spectacle. Oroyan–a stellar dancer for Zenon, Shapiro & Smith, Black Label Movement, and other modern companies–teams up with Laura Selle Virtucio, another stellar dancer for most of the same companies, to tell the story of an explosive affair. Oroyan has a physique and a firecracker energy that elicit small, startled noises from audiences; Selle Virtucios sheer emotional power makes people moan, while her soaring strength is gasp-worthy. Put those two in a spaceflying together in gymnastic exuberance, flipping apart in animal fitsand youve already got a spectacle. Add a four-man pick-up rock band, a raucous set (designed by Collin Sherraden and painted by Danny Sigelman), and a zinging sense of humor, and you have an audience in a lather.

Whats most surprising about Oroyan isnt his choreographic skillI saw invention and energy, but nothing I wouldnt have expected from a dancer of such ability and experienceor even his showmanship: its his sure handling of emotion. Brown Rocket goes from zero to sixty, lust to disgust, one characters perspective to another, sweet to funny, make-up to breakup, without a single seam showing. Oroyan is a born storyteller. Not the scratchy, difficult postmodern kind eitheryou get the feeling he could write the next Princess Bride, or that George Lucas really ought to have consulted him on the recent Star Wars flicks. Hes that kind of orchestrator.

Altogether, Brown Rocket is so smoothly and directly delivered to your door that it feels more like a Broadway musical than your usual dance performance. As such, Im not sure Im all that interested in it, as in I dont think Ill be mulling it over a few weeks from now. But frankly, right now, Im just too entertained to care.

About the writer: Lightsey Darst writes on dance for Mpls/St Paul magazine and is also a poet and editor of mnartists.orgs What Light: This Weeks Poem publication project.