Clothes that Made the Man

Camille LeFevre reviews the Goldstein Museum's retrospective of master costume designer Jack Edwards's storied career - at the Guthrie, as a holiday display guru for Dayton's department store, and more. The show is on view through May 20.

WHAT YOUNG CHILD DOESN’T LIKE TO PLAY DRESS UP? Whether it’s a weekly pastime or relegated to Halloween, the thrill of shedding one’s everyday clothes and inhibitions — for a store-bought or handmade costume, mom’s purple-tulle prom dress or dad’s old suit, a superhero cape or an outfit of one’s own design — offers a moment of bona fide transfiguration. Once you’re dressed for the part, new identities can be tested and imaginary adventures undertaken in earnest.

Is it any wonder dress-up still holds its allure, even after we grow up? A black wool dress becomes one’s funeral costume, a thin yet effective carapace for holding in grief during community rituals of letting go. A trim jacket and pants is the go-to teaching or meeting outfit, projecting an aura of organization and professionalism as one strides through the door. Spangles signify fun — or sluttiness. Sky-high heels: singular, enviable fashion sense — or sluttiness.

Theater people know well the power of costume to create and communicate character. None more so, perhaps, than Jack Edwards, who dressed the Guthrie Theater’s actors for nearly 20 years. He remains quite the character himself, adorned in dramatic clothing and accessories that themselves appear as costume, but speak — like a second skin — of a storied, creative life.

At the opening of the exhibition Character in Costume: A Jack Edwards Retrospective, assembled by and on view at the University of Minnesota’s Goldstein Museum of Design, Edwards held court in the small gallery. Wearing a heavy silver collar of African design — one of his many signature, oversized necklaces — he jovially regaled an appreciative audience with stories of his youth, when his mother designed and sewed his clothes.

Apocryphal or not, Edwards’s real story begins after he graduated from Ithaca College in 1954, when he says he lit out for New York with five bucks in his pocket. Along the way, he also abandoned his family name: Kutz. The Goldstein does an admirable job of sketching the highpoints of Edwards’s career in the ’50s and ’60s, with an assortment of photos, playbills, news clippings, and video clips that touch on Edwards’s work with Sir Cecil Beaton (on a musical about Coco Chanel, starring Katherine Hepburn), creating opera gowns for singers Mildred Miller and Martina Arroyo, running the costume shop at the Santa Fe Opera and assisting Bob Mackie in creating costumes for a season of the Carol Burnett Show.

______________________________________________________

Edwards has spent decades dreaming, drawing, cutting, and sewing the wearable theater that has transformed countless actors into memorable characters.

______________________________________________________

But the exhibition’s real highpoints are the couture and costumes themselves, notable for their astounding technical and textural detail. An exquisite cocktail dress for Miller — made of braided olive-green wool, twisted and crocheted into abstract shapes over net — has a timeless simplicity and retro appeal even now. A wedding ensemble includes a gown of hand-sewn, overlapping tucks that, once again, layer texture over a simple form. At the gallery entrance, two of Edwards’s more recent confections provide an exquisite study in contrasts: A red concert ensemble for singer Lorie Line includes a gown with sweetheart neckline, made dramatic by a dropped waist. The gown is topped by a gigantic boa, whose feathers layer high above the neckline to create an Elizabethan collar. Next to the Line ensemble is a woman’s gray silk Victorian coat, a costume from a Guthrie production of Great Expectations. Tiny black threads feather the jacket’s ruffles and rosettes with contrasting detail. In these two manifestations of “dress-up” lie all one really needs to know of Edwards’s expertise: his remarkable range across eras and purposes, his deft handling of detail and the flamboyant gesture, the migration a single material –the feather — and its effects into costumes of diverse characters.

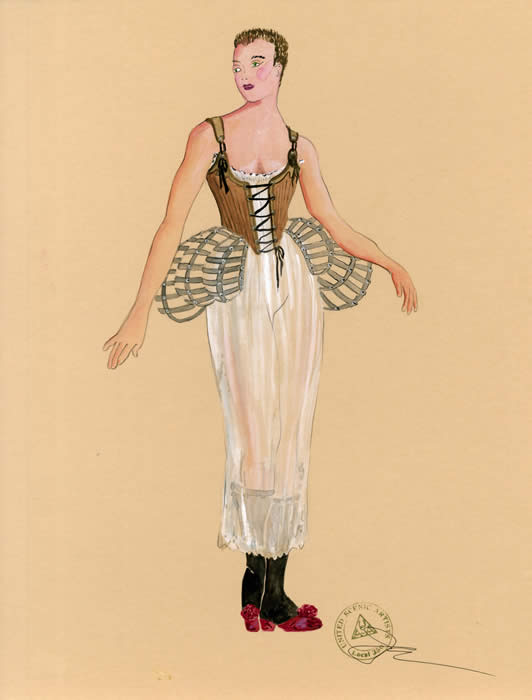

But, of course, there is more. A cluster of manikins — men, women, children — model Edwards’s complete costumes (including hats and gloves) for such Guthrie productions as The Imaginary Invalid. Across the room are fully costumed figurines from Edwards’s fantasy vignettes for Dayton’s (later Marshall Field’s) famed eighth-floor holiday displays; these include characters from his tableaux for Wind in the Willows and A Christmas Carol. Adjacent to the storybook characters are pages from Edwards’s “prop bible” as well as pictures of dancers posing as models for the figurines. At the front of the gallery are Edwards’s artfully detailed costume sketches for the Guthrie — each stamped by Limited Scenic Artists Local 350 and bearing Edwards’s signature.

Edwards led the Guthrie’s costume shop for 18 seasons, and he remained at Dayton’s for 12 years. He designed Line’s costumes for her stage shows in the ’90s and even worked his magic for Prince, creating ferocious, skin-baring costumes (his drawings show skulls, snakes, animal familiars) for Purple One’s dance-musical, Ulysses, which premiered in 1993 at Glam Slam.

Images of Edwards in his younger days show a dashing dandy (think Stephen Ouimette as the flamboyant director Oliver Welles in Slings and Arrows); one can easily imagine the fellow you see in those shots hobnobbing with the likes of Beaton, Burnett and Lauren Bacall (who is pictured on one of the playbills). But Edwards’s professional life has largely taken place backstage — dreaming, drawing, cutting, and sewing the wearable theater that has transformed countless actors into memorable characters. For Edwards, the allure of dress-up has never faded. And if you find yourself gazing covetously at that green wool shift, a well-turned hat or snake-entwined short-shorts, then, thankfully, neither has the allure of dress-up faded for you.

______________________________________________________

Related exhibition details:

Character in Costume: A Jack Edwards Retrospective is on view at the University of Minnesota’s Goldstein Museum of Design through May 20.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Camille LeFevre is a Twin Cities arts journalist and author, who also teaches arts journalism at the University of Minnesota.